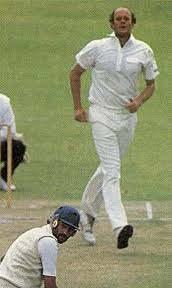

Vintcent Van Der Bijl

Martin Chandler |

Voltelin Van der Bijl played for Western Province in their second ever First Class match, in December of 1890, and in total played in seven First Class matches over 14 years. His brother Vintcent, a year younger, played with him twice. It is difficult at this distance in time to discern very much about the brothers, other than that both seem to have been all-rounders and serviceable cricketers. Luckin’s History of South African Cricket contains a photograph of V Van der Byl (sic), but it is not clear whether the image of a man dressed in hunting attire is Voltenin or Vintcent, and it also makes reference to another Van der Byl being involved in the game in the 1860s. It would appear therefore that the family were established in South Africa well before the brothers were born, so Vintcent being educated in England, at Wellington College, would suggest the family must have been reasonably well off. That indication is perhaps reinforced by the fact that Voltelin, invited to tour England in 1894, had to turn the offer down due to the demands of his business.

Vintcent’s son, Pieter, made a First Class debut at the age of 18 in 1925. Also a Western Province player Pieter made a number of appearances over the following three seasons as a wicketkeeper. His batting was modest, only an unbeaten 60 against Eastern Province taking his average as high as 15. He used his time to gain a degree at the University of Cape Town and by 1929 was in England. He spent two years, 1931 and 1932, at Brasenose College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. A very tall man who was not at all quick on his feet in his first year he appeared for the University just once, scoring 16* and 0 against Yorkshire and, despite being a man with an essentially placid disposition, his greater sporting success was found in the boxing ring.

Against that background it is perhaps surprising that the following summer found Pieter a regular in the Oxford side. He was third in the batting averages with 540 runs at 45.00. There were five half centuries and a best of 97* against Essex. Wisden summed Pieter up by reporting that he seemed to play an unnecessarily laboured game for a man of such fine physique. Patient with a very strong defence, he usually took a long time to settle down and seldom allowed himself the luxury of an attempt to force the game. His best known innings is one of just seven, in the Varsity match at Lord’s. Cambridge’s young fast bowler Ken Farnes peppered Pieter with plenty of short pitched bowling which, too slow to get out of the way of, he courageously allowed to repeatedly hit him about the body.

After leaving Oxford Pieter went back to South Africa to teach and eventually, at the age of 29 in December 1936, he recorded a First Class century. It was a big one too, 195, but against a pretty ordinary Griqualand West side. The innings gave him confidence however and he enjoyed a good season in 1937/38. It was only the second time he had played as many as six matches in a South African season but he averaged more than 60. The next summer the MCC were due for a five Test series and the South Africans, who had won in England in 1935, were keen to do well.

The home captain was Alan Melville and the South Africans had a problem with opening batsmen. Melville had skippered Oxford University in 1932 and remembered Pieter’s bravery against the pace of Farnes, and he made sure he was in the side. Pieter showed all the courage he was known for and blunted the threat of Farnes. He played through the entire series and averaged 51.11. In the notorious timeless Test he was in his element, scoring 125 in more than seven hours in the first innings, and in the second being within three of becoming the first South African to record twin centuries in a Test when he was caught at short leg by Eddie Paynter from the bowling of Doug Wright. Two deliveries before that he had tamely patted a full toss back to the bowler.

When War broke out later in 1939 Pieter soon enlisted with the Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Rifles. He saw active service North Africa on a front that waxed and waned in the early years of the war. In 1942, then a Lieutenant, he was awarded the Military Cross. His best known act of gallantry arose from a rescue mission. Pieter spotted, after a confrontation in which the Allies had been thoroughly defeated, a number of casualties lying on the battlefield. Despite their vehicle thereby being an easy target Pieter and his driver went out and gathered in the wounded before, despite shells exploding all around them, managing to return to safety. The Military Cross had been awarded a little earlier in the campaign and arose out of Pieter, accompanied by the same driver but, this time without a vehicle, volunteering to go behind enemy lines to capture a prisoner for interrogation. Needless to say the mission was successful.

By the end of 1943 Pieter had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was leading his men into Italy. Unfortunately there his war ended when he was injured in an accident that meant he was invalided back to South Africa. His injuries meant he never played cricket again, but he went back to teaching and, with the wife he met during the war, had three children of his own. A fierce opponent of apartheid it is worth noting that in the 1950s he joined a number of marches protesting at the actions of the Nationalist government, and specifically their removing the right to vote from the non- white population.

Pieter died peacefully at home from a heart attack in 1973 at the age of 65. He had lived long enough to watch his son, another Vintcent, rise to the top of the domestic game in South Africa and, although the opportunity never came for the tour to take place, gain selection for the South African party that was due to visit Australia in 1971/72. To this day with, perhaps, a little competition from Australian Cec Pepper and the Philadelphian Bart King, Vintcent Van der Bijl remains the finest cricketer never to have played a Test match.

As with any white child of professional parents in South Africa Vintcent had a privileged upbringing, which included every opportunity to play sport. A big man like his father (he ended up at around 6’ 7’’ in height with size 14 feet) as a youngster he was keen rather than showing any great talent. On the Rugby field his size meant he was a popular choice as a lock forward, and he had a formidable reputation as a place kicker. He was also a talented athlete and showed considerable ability at putting the shot and throwing the discus. Despite all that cricket was his first love, but following in his father’s footsteps as a batsman he gave no indication that he would ever aspire beyond club cricket.

It was around the age of 15 that Vintcent finally began to take his bowling seriously. His height and the lift that enabled him to generate immediately made an impact and whilst he didn’t, to start with, run through sides his promise was obvious and progress was swift. He had much assistance from many coaches but in particular, once he got to University, from former Springbok skipper Trevor Goddard.

Aged 20 when he made his Currie Cup debut in 1968 Vintcent had the unpleasant experience of being reported to the South African Cricket Board for ‘irregular tactics’ during the match, in other words cheating. What happened was that Vintcent had taken some lip ice onto the field with him after lunch having been advised by his skipper, Barry Versveld, of its usefulness in returning shine to the ball. Versveld assumed, quite wrongly as things turned out, that Vintcent was aware that use of the ice was illegal. He wasn’t, and shortly afterwards proceeded to produce the lip ice from his pocket and start polishing the ball. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately depending on your point of view, Vintcent did this whilst standing next to the horrified umpire and so his only real punishment was embarrassment.

As a bowler Vintcent was unusual for a paceman in that he did not rely at all on any sort of intimidation and indeed was a friendly figure on the field. He lumbered in over around fifteen yards from the direction of mid off and seldom bowled short. He was a genuine fast medium, but no more, although his height meant he hit the pitch very hard and extracted whatever bounce and movement there was. Metronomic accuracy also had the effect of frustrating batsmen who found him very difficult to score from.

Between 1968 and 1972 Vintcent was at Natal University in Pietermaritzburg, and after he graduated he went straight into teaching at Maritzburg College. He had the time off he needed to play in the limited number of Currie Cup matches that were played in those days and was largely content with that. He carried on his record breaking ways and by the end of the 1979-80 season he held most of the more important South African domestic records. He was the leading wicket taker in Currie Cup history (420), and for Natal (458). No one had taken more than his best (65) wicket haul in a season. He had also turned himself into a sound fielder, and whilst he never quite managed to bat with sufficient consistency to be considered an all-rounder he developed into a very dangerous hitter in the lower order with seven First Class half centuries to his name.

There were plenty of top quality South African cricketers plying their trade in the English game in the 1970s and whilst county supporters, save those who dug around the closing pages of the ‘Overseas Cricket’ section of Wisden, had no cause to have heard of Vintcent his was a name that was mentioned to county headhunters from time to time. Occasionally enquiries were made, but none that ever tempted Vintcent, and he certainly seems not to have had an offer from Kerry Packer to join World Series Cricket.

By 1979 however Vintcent had become restless and despite still enjoying his teaching job decided that he wanted some financial security for his family, so he decided to take a job with the multinational paper company, Wiggins Teape. At the same time Middlesex were looking forward with some trepidation to a summer without their talismanic overseas fast bowler, Wayne Daniel, who they confidently expected to be party of the 1980 West Indies tour. Committeeman and former England wicketkeeper John Murray was tasked with the job of making an offer to Vintcent.

Initially Vintcent was reluctant, feeling he needed to commit himself to Wiggins Teape rather than join the company and then take five months off. Middlesex were nothing if not resourceful however and, the company’s managing director being a Middlesex man through and through, he was persuaded to agree an arrangement that enabled Vintcent to play a full season for the county and spend some of his down time at Wiggins Teape’s UK base in Basingstoke, and the deal was done.

It has always been known that Middlesex skipper Mike Brearley was deeply unhappy about the signing, something he only heard about as a fait accompli whilst leading England in Australia. In large part that was undoubtedly due to his irritation at not being consulted at all, but the low profile that Vintcent had despite his outstanding record did not assist. Add in the fact that Vintcent was, at 32, approaching the veteran stage for a pace bowler together with Brearley’s long standing objection to apartheid and the problem becomes an entirely predictable one.

Meeting Vintcent would doubtless have given Brearley some reassurance on the latter point, the genial giant’s views on that subject rather mirroring those of his father. Brearley would however have been concerned about his new overseas player’s form, as in three pre-season club matches Vintcent took just a single wicket. Not totally familiar with English conditions Vintcent had visited England on just one previous occasion when he had toured with a strong Wilfred Isaac’s XI, although no First Class matches were played. As a result of these disappointments Vintcent decided to take to the nets with county coach Don Bennett, and spent several days regaining his fitness and, with Bennett’s help, his outswinger.

In 1979 Middlesex had finished fourteenth in the Championship. Twelve months later the famous pennant was fluttering over Lord’s, and the county had also won the premier List A tournament, the 60 overs a side Nat West Bank Trophy. In the other two competitions they had finished third in the 40 over John Player League and were losing semi finalists in the 55 overs a side Benson and Hedges Cup. At the end of the season Brearley, by now both a friend and an admirer of Vintcent, described him as the biggest single factor in our success.

In the First Class game Vintcent took 85 wickets at 14.72 to finish second in the First Class averages. The only man in front of him was Richard Hadlee, whose season was restricted to seven matches by injury. There was plenty of competition in that Middlesex side for the wickets as well, spin twins John Emburey and Phil Edmonds both enjoying productive seasons and, much to their delight, the county also had Daniel available, the West Indians having decided they could do without him. None of them however took as many wickets as Vintcent nor at as low a cost.

By modern standards Vintcent’s performances in the List A season are just as impressive if not more so. He took only 25 wickets in 26 matches, but his economy rate was a mere 2.79. By way of example in the Gillette Cup final victory over local rivals Surrey his spell of 12-0-32-1 was one of the decisive contributions. With the bat there were also useful knocks, in particular in a Championship fixture at Lord’s against Nottinghamshire. The match followed Middlesex’ only real wobble all season after they had lost two consecutive matches. Asked to bat on a damp pitch they slumped to 86-6 before Vintcent joined Graham Barlow. To start with the big pace bowler presented an atypical dead bat to the bowling, but once the partnership became established he hit the ball hard and straight and ended up on 76 before getting out unselfishly in trying to get the score to 300 within 100 overs in order to get an extra bonus point. Twelve wickets for Emburey then brought an innings victory – Vintcent never did get a First Class century.

Having a full summer in England meant that when he got home to South Africa for his own domestic season Vintcent was already fit and raring to go and he had an extraordinary summer as he took 54 wickets at just 9.50. Much effort was put in by many to try and persuade Vintcent to return to Middlesex for a second summer in 1982, but although he was tempted he decided to stick to his original promises to Wiggins Teape. There was therefore just one valedictory appearance in the traditional season’s curtain raiser at Lord’s between the Champions and the MCC. On a personal level the match was not a great success for Vintcent, but he greatly enjoyed the farewell.

On his own admission success in England had rather gone to Vintcent’s head and he had developed a degree of arrogance and unpleasantness he had never shown before his time in England. The issue came to a head in the List A final for the Datsun Shield in early 1982. Playing for Natal against Western Province at one point in the Western Province innings, as Vintcent turned to return to his mark, he saw the non-striker Allan Lamb out of his ground and threw down the stumps and appealed. The ball was not technically dead, and Lamb had to go. In the end it mattered little as Western Province ran out winners by two runs, but not before they themselves had perpetrated a not dissimilar run out on Natal. It is clear from the post match photographs that the players on both sides were less than happy at the way the match had been played. In fairness to Vintcent it should perhaps be pointed out that in the autobiography he published in 1984 he accepted his run out of Lamb had been wrong.

Vintcent’s final season of First Class cricket was in 1982/83. He was 35 at the end, but he helped Traansvaal to win the Currie Cup that season and with 52 wickets at 18.76 was the pick of their bowlers. Perhaps with his advancing years he was beginning to struggle with the limited overs game? Certainly not is the answer to that one, 30 wickets at 15.53 and economy rate of 2.92 providing further evidence that he could surely, had he so wished, have played on for a few more summers despite his fondness for the tobacco products manufactured by Alfred Dunhill Limited.

As he aged Vintcent did eventually come back to cricket and took up administrative roles with South Africa and then, in 2008 being appointed as the ICC’s umpires’ and referees manager. His most recent employment, and surely his most challenging, has been as a consultant to Zimbabwe Cricket

Leave a comment