The Demon’s Inheritors

Martin Chandler |

JJ Ferris has the second best bowling average in history, paying a mere 12.70 runs each for his 61 Test wickets. He is still second in the list if the 13 cheap wickets he picked up in his one Test for England are disregarded and his record stands simply on his eight Tests for Australia against England.

Charlie ‘Terror’ Turner is sixth in that list, all 101 of his wickets coming in 17 Tests for Australia against England, at a cost of 16.53. Ferris has the second best strike rate as well, or seventh if that England performance is left out of account. The Terror is further down that list, but 41st over the entire span of Test cricket is still impressive.

In all of Ferris’ Tests for Australia he partnered Turner, so a successful pairing to say the least. It seems remarkable that of those eight matches Australia won just one, and lost all of the other seven. In Turner’s nine Tests without Ferris Australia did better, winning three, but they still lost four.

Another curious feature of the pair is their longevity, or rather lack of it. In an era when cricket careers were generally much longer than they are today Turner played his last Test at 32. As for Ferris he was only 23 when he played his last Test for Australia, and still not 25 when he made that sole appearance for England against South Africa.

Both men were New South Welshmen and worked as bank clerks, although their backgrounds were geographically rather different. The Ferris family had migrated from Ireland after the potato famine that caused havoc there in the late 1840s. When the cricket season of 1886/87 dawned Ferris was 19 and yet to make his First Class debut.

Turner’s forebears came from England, and had left the British Islands a few years earlier than those of Ferris. Turner was 24 at the beginning of the 1886/87 summer and had made his First Class bow four years before that, for New South Wales against Ivo Bligh’s England. Bligh’s side defeated New South Wales by an innings and 144. The debutant took a solitary wicket at a cost of 76 runs. His victim was George Vernon, the Englishmen’s number ten and the last man dismissed. In the intervening three years he had appeared in three more First Class fixtures conceding 62 more runs. He didn’t take a single wicket.

On 19 November 1886 New South Wales began a match against Alfred Shaw’s XI, a side organised by the veteran Nottinghamshire bowler and captained by his teammate, the great professional batsman Arthur Shrewsbury. Later in the tour Shaw’s men were scheduled to play Australia twice, and those matches were the 25th and 26th Tests. Faced by an opening attack comprising a debutant and a man with one wicket for 138 in four years the tourists must have been confident.

So what sort of bowlers were these men? Turner was about 5’9’’ in height and weighed about 12 stone, so he must have been a stocky and powerful figure. He was a right arm finger spinner, and was clocked at 55mph in 1888. It would be interesting to know exactly what methodology was used. There is a fairly detailed explanation in Turner’s 1926 book The Quest For Bowlers, but sadly the key item is referred to simply as a delicate machine. It seems certain however that the famous soubriquet was not descriptive of the pace at which Turner bowled.

Some modern sources describe Turner as fast medium, but 55mph does not a fast medium bowler make. Wisden described his pace as above medium, and HS Altham in his History of Cricket, published in 1926, as medium. Both sources were agreed on his pace off the pitch, the fabled heavy ball. The Almanack, unusually effusive, wrote of a fine break from the off and a wonderful yorker. There is, of course, no film record.

Photographs suggest that Ferris was about the same height as Turner, but slimmer. He was a left armer and as a consequence spun the ball in the opposite direction to Turner, although he had a highly effective arm ball. He seems to have been considered slower than Turner and in describing his action CB Fry talked of something uncommon in the flight, a phrase Max Bonnell chose for the title of his biography of Ferris. CB went on to further explain his comment as referring to a tendency for the Ferris delivery to dip at the end of its flight, as it was almost upon the batsman.

Prior to 19 November there had been a couple of matches against odds and, by the standards of the time, a high scoring draw against Victoria. The substandard wicket at the SCG (then known as the Association Ground) notwithstanding Shaw’s men would not have been expecting, on winning the toss and choosing to bat, to be dismissed for 74 in little more than a couple of hours by a pair of unknown bowlers. That is exactly what happened however. Ferris took 4-50 and Turner 6-20. Between them they bowled all but two of the overs.

In their second innings the Englishmen did a little better, bowled out for 98. This time Turner and Ferris got a total of six overs rest. Turner took 7-34 and Ferris 3-49. New South Wales got home by 6 wickets. In a rematch three weeks later Shaw’s side triumphed by nine wickets, but all eleven English wickets that fell belonged to Turner (8-80) and Ferris (3-81).

Turner and Ferris maintained their form through two games against Victoria and both deserved selection for the first of the two Tests back at home at Sydney. The start was even more sensational than that of 19 November. This time it took less than two hours to dispatch the tourists, who were all out for 45. Turner and Ferris bowled through unchanged, 6-15 and 4-27 respectively. It did not however prove to be enough as the English professionals restricted the lead to 74, and then scored 184. Turner was a little out of sorts and took only two wickets. Ferris had 5-76 but their batsmen couldn’t quite carry Australia home. The second Test was more comfortable for the visitors who ran out winners by 71 runs, but there were nine wickets each for Ferris and Turner. They bowled 145 four ball overs between them. The three support bowlers contributed just 27.

Two English sides toured Australia in 1887/88, one led by Arthur Shrewsbury and the other by George Vernon. In early February the two sides combined and what has become classified as a Test match played. The pattern was the same as the previous year, the home side’s batsmen not scoring enough runs to complement the efforts of Turner (12-85) and Ferris (6-103).

In 1888 Turner and Ferris came to England with the side led by Percy McDonnell. There were three Tests scheduled, all of three days duration. In the event none of the matches went to a third day. Australia won the first and England the second and third to take the series. The wickets were poor, as a quick look at the scoring amply demonstrates. Of the ten completed innings in the series (both of England’s successes were by an innings) as many as seven resulted in all out totals of 100 or less.

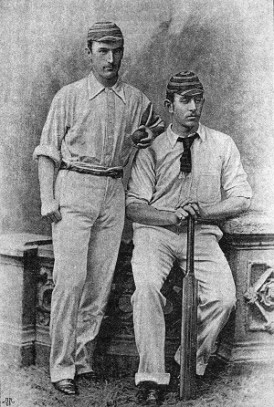

There was a great deal of work for Turner and Ferris on the tour as a whole. Of the 40 matches Ferris played in them all, and Turner missed only one. For Turner there were 314 wickets at 11.38, and for Ferris 220 at 14.23. The next highest wicket taker was Harry Trott with 48. The 1889 Wisden was the first to carry a photographic plate. The feature Six Great Bowlers was the reason. There were five separate images, the central one being of Turner and Ferris, the only time one of the many great pairings in the game have been treated in that way by the Almanack.

Australia, with their two spearheads, were back in England two years later. The third of the three Tests, at Old Trafford, does not appear in the record books because it was washed out without a ball being bowled. The two Tests that did start were both won by England. This time there were 37 matches, and Ferris and Turner were each allowed to miss two. Their dominance was not much diminished, both managing 215 wickets. Turner paid marginally less for his, 12.15 as opposed to 13.43 by Ferris. This time the next highest wicket taker was the 23 year old coming man, Hugh Trumble, who took 53 wickets in 25 matches. In the two Tests Ferris was as impressive as ever, with 13 wickets at 13.15. Turner was rather subdued in comparison, his six wickets costing 26.50 runs apiece.

The 1890 tour was the last visit by an Australian team to England for three years and by the time Jack Blackham’s 1893 side arrived Ferris was no longer available. On his first trip to England in 1888 Gloucestershire had shown an interest in recruiting Ferris as a professional. It seems they finally managed to persuade him to join them during the 1890 tour. In those days in order to be eligible to play in the County Championship a player had to have lived in a county for at least two years, although it seems the requirement was not always rigorously enforced.

Ferris did return to Australia after the 1890 visit and played against South Australia and Victoria in December, taking 20 wickets, before setting off for England in January 1891. After a seven week sea voyage he arrived, and it seems no one objected to his being treated as having been resident in his adopted county since June 1890. In any event his Championship debut came in June 1892.

In the meantime there was the summer of 1891 during which Ferris had to occupy himself. He took a job with a firm of Bristol stockbrokers, although he still managed to play 25 cricket matches for ten different teams and, in fact, had the most successful of his five summers in England with the ball. He took 70 wickets at 15.57. If that were not enough time off from his work he then spent three months with a private tour of South Africa captained by Walter Read of Surrey, one of only three men in the party to have played for England against Australia. Another team, led by Grace, was actually in Australia and playing Tests at the same time, and Read’s combination was in no way representative of the strength of English cricket. That does not however alter the fact that the penultimate match of the tour, eleven a side and scheduled for three days, now has Test status. Ferris took 13/91 as the Englishmen overwhelmed their hosts by an innings and 189 runs.

Gloucestershire must have been excited by the reports that got back to them about the form of their star signing. On the tour as a whole he took more than 200 wickets at an average of around six. Read described him as the mainstay of his team but the truth is the tourists were victims of their own success, the matches generally being so one-sided that very few spectators bothered to turn up and financially the tour was a failure.

Back in Gloucestershire Ferris’ first season was not a great success. He started it with a first ball duck and ended with 46 wickets at around 24.10 and the county won just once and ended the summer seventh of the nine sides in the Championship. One aspect of the Ferris game that did improve in 1892 was his batting. He had never been an out and out rabbit but a couple of half centuries was the mark of a man capable of a handy innings or two rather than a genuine all-rounder. In England he definitely got better and in 1893 scored 1,000 runs including five half centuries and, with 106 against Sussex, his only First Class century. The other side of the coin was 53 wickets at almost thirty runs each.

The batting improvement in 1893 was not sustained the following summer and whilst with the ball Ferris shaved as many as eight points off his average he was not given the ball anything like as much and his haul of wickets fell to 44. In the 1895 season Ferris turned 28, and should have been in his prime, but instead he suffered a finger injury early on and never produced much in the way of form. The county decided not to renew his contract and he returned to Australia. Wisden was blunt in the extreme writing that he proved an utter failure ……. he had lost his pace, his spin, his action and everything.

Back in Australia Ferris continued to play cricket, and there were three more First Class appearances, but although he did score 51 in the last of them there were only two wickets and he was not persevered with.

In July 1899 Ferris set sail for South Africa. History does not record why but Bonnell is confident that he was simply looking for a new start and new opportunities. In the end he signed up for the South African Light Horse, a volunteer corps, in February 1900. In October he left his military service and went back to civilian life in Durban. As the Light Horse was not part of the regular army few records were kept and of those that were few survive. It is clear from what there is that Ferris did see some action in the Boer War but, on the other side of the coin, that he was discharged ignominiously. Just what his transgression was is not clear.

A few short weeks later JJ Ferris was no more. Over the years the cause of his death has been told and retold as being enteric fever, or typhoid. It is a disease generally contracted through dirty water, and in the Boer War more British casualties succumbed to that than did to the fighting so it was certainly an entirely credible explanation. It is not however one that is accepted by Bonnell. Contemporary reports state that, effectively, a healthy looking Ferris went out, got on a tram and keeled over. He could not have been suffering from enteric fever. He might, like his father before him, have suffered an aneurysm or, opines Bonnell, may have taken his own life. A Reuters cable referred to Ferris having died suddenly, a common euphemism of the time for suicide.

Turner never looked as good again as in his early years, but he did play nine more times for Australia after Ferris decided to throw in his lot with Gloucestershire. He was therefore, like Ferris with Read’s side, also playing Test cricket in 1891/92, against Grace’s side, and he came back to England for a third visit in 1893 before playing a part in the 1894/95 series, aptly described by David Frith as the first great Ashes series.

The 1891/92 tour has an interesting background. Australia was in the grip of a recession and interest in cricket, following the defeats in 1888 and 1890, was not high. A benefactor, Lord Sheffield, stepped in at huge personal cost. He paid Grace an eye watering £3,000, the equivalent of around £350,000 today, as well as making generous provision for the expenses of himself and his family. Grace’s was a strong side and won the third Test by the massive margin of an innings and 230 runs. Australia had however won the first two Tests and therefore took the series. Turner took 16 wickets at 21.12 and was Australia’s leading bowler.

The 1893 tour was not a happy one. Performances on the field were poor and the one decided Test of the three match series was won by England. That it wasn’t 2-0 to England was, unusually, largely down to Turner the batsman. Had he not, despite being in pain from a dislocated finger that WG had had to put back in place for him, hung around for 27 runs in a last wicket partnership of 36 in his side’s second innings England would have had the time they needed to force a win. With the ball no longer was Turner his side’s best bowler in the Tests, and he had a relatively modest haul of 11 wickets at 28.63. His figures on the tour as a whole were still impressive enough, but in the Tests he was bested by George Giffen, a man of whom he was never to have a high opinion. The Terror considered Giffen to be a selfish player.

Following the 1893 tour Turner might have joined Ferris in county cricket. He received an offer of a five year deal at Sussex, which he was prepared to accept. In the event however Lord Sheffield, the county President, was not prepared to commit the funds needed to make the deal work. So Turner had to return to the depressed New South Wales economy where, the bank at which he had previously been employed having ceased trading, he set himself up in business as a ‘general merchant’

Turner took his place in the Australian team for the first Test against Drewy Stoddart’s England side of 1894/95. This was the first and, until an Ian Botham inspired England at Headingley in 1981 repeated the feat, only Test in which a side following on has coming come back to win. Turner took only three wickets, so could certainly have done better. England went 2-0 up in the second Test. It was almost like the old days as Turner took 5-32 in an England first innings total of just 75, but the visitors came back strongly and won again. Injury kept Turner out of the third Test, won by Australia, but was back for their handsome innings victory in the fourth. England were shot out for 65 and 72. Turner took 3-18 and 4-33.

Remarkably Turner was left out of the side for the final Test, one of the great selectorial blunders as Australia’s bowlers allowed England to chase down a fourth innings target of 298, at that time the largest ever achieved by a distance, for the loss of just four wickets. The decision to leave Turner out was ultimately down to skipper Giffen who clearly let personal antipathy get in the way of what was best for the side. Turner was furious and immediately announced his retirement from Test cricket.

As with many such situations the passage of time soothed injured feelings and Turner might well have continued his Test career with a final trip to England in 1896. He was called up at the last minute and accepted the offer but in the end he didn’t go, citing an inability to cover his business commitments at such short notice. That may well have been a factor, but also at work no doubt was a substantial debt to Shaw and Shrewsbury. They had provided him with a stock of equipment after discussions on the 1893 tour, but the supply of cricket equipment was not a business that went well for Turner and he had not been able to pay for all the stock.

Whether Turner would have made any impact in 1896 must be questionable. He was only 34, but had had a modest season by his own standards in 1895/96 and the following season, his last, he managed just three wickets at 72 runs each in his four matches. The only other First Class match he played was 13 years later, his own testimonial match.

Although life after cricket was kinder to Turner than it was to Ferris he certainly struggled in business. In difficult times he was unable to keep out of debt and was taken to court over small debts more than once in the late 1890s. Eventually he threw in the towel and in 1907 went back into banking, and spent another 24 years there until, in 1931 when he was 68, his employer’s retirement policy brought that to an end. Turner did some writing, and also appeared in radio broadcasts talking about cricket. He had a decent run at retirement as well, living on until New Year’s Day 1944 when he died in Manly Hospital of what was quaintly and unattractively described as senile decay – he was 82.

Hi Martin,

As usual, quite a good article!

There’s one correction though.

The 55 mph speed measurement you are mentioning above of Charlie Turner that was recorded at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich was in 1893, not 1888.

The Evening Star on October 28, 1893 contemporaneously reported on the story and the link is available for your reference below (technically the 81 ft/s recorded converted is 55.3 mph and my limited understanding from Turner’s biography was that he wasn’t looking to bowl flat out):

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD18931028.2.29.11

The reason why I think this matters is because as you alluded to above in 1893 Charlie Turner was no longer the same bowler as the Charlie Turner of 1888.

While his overall tour statistics were still good as you described above often against weaker opposition, his results in fact during the 3 Tests and 175 overs he bowled paint the picture quite clearly:

11 wickets; 28.6 Average; SR 79.6.

This was comfortably his worst average for any of the series he played in. He was outbowled by 5 bowlers – including by fellow Australian George Giffin.

And the reports in Wisden as well as in other publications at the time lamented how none of the Australian bowlers were quick or even fast medium enough at the time, with them also indicating that Turner had gotten significantly slower.

I recall them stating they desperately needed someone even as fast medium as the late Fred Spofforth, with them mentioning how Richardson was far quicker.

This gives me reason to believe that Turner was probably in the earlier stages of his career probably 10-12 miles per hour quicker.

This would place him roughly the mid to late 60 mph mark on average, with a quicker ball that was probably faster still.

And the accounts of him being medium pace given this context would largely make sense.

Comment by Pratham Chhabria | 3:31am GMT 23 February 2023