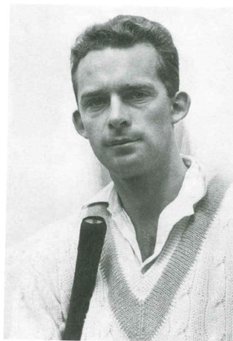

The Bob Barber Story – Part 1

Martin Chandler |

Bob Barber’s name is one of those that tends to cause cricket lovers’ brows to furrow. It is certainly familiar, but difficult to associate with anything tangible. The usual reaction that follows, a minute or two after he is mentioned, is along the lines of “Didn’t he play a few times for England in the 1960s?”

Those “few” Test caps were in fact 28. For an opening batsman his record is not the best, but an average of 35 is to be respected. There was just one century, of which more later, and what a magnificent innings it was, one of the finest Ashes innings ever. Barber also remains, behind Doug Wright, the second most successful English leg spinner since 1946. The competition in that field is not particulary intense, but 42 wickets, including that of Garry Sobers twice in just two Tests against the West Indies, show a far from negligible talent.

The reasons why Barber does not loom large in the affections of the English cricketing public are not difficult to spot. His Test career belonged to an era which, despite his own valiant attempts to extricate cricket from the general mood of the time, saw the game played very defensively and, more significant then than now given the ease with which overseas Tests can be viewed today, his record on tour is markedly superior to that at home. In 11 Tests in England he scored 539 runs at 26.95 with just three fifties. Elsewhere there were 17 Tests, 956 runs at 43.45, and six fifties to sit alongside that swashbuckling 185 at the Sydney Cricket Ground in January 1966.

In the 1960s the way the game was played tended to be dictated, with the honourable exception of the men from the Caribbean, by a desire to avoid defeat. The nadir was reached in 1964 when Australia, 1-0 up in the series following victory in third Test, went out in the fourth at Old Trafford and took more than two days and 255 overs to compile an innings of 656-8, with England then using 293 overs to end up 45 behind. At the end of the final day there was time for just two overs of the Australian second innings.

A week after that tedious affair Warwickshire defeated the Australians in the last over of a thrilling finish at Edgbaston. A crowd of 20,000 on the first morning saw Barber treating the tourists’ attack, including Garth McKenzie, with complete disdain as he hammered a century before lunch. In the fifth Test England picked Barber, for only the second time in a home Test, to try and up the tempo. He got a start in both innings before being dismissed, but rain curtailed the game, and the Ashes stayed with Australia.

As to Barber’s record being better overseas that is in part explained by his simply being able to see the ball better. His sight in his left eye is slightly defective and that, so the theory goes, is part of the reason for his batting left handed when he does everything else with his right. Barber’s own, interesting opinion is that many young players bat ‘the wrong way round’. During his playing career he was told by an eye specialist that for most people the right eye is dominant. On the basis that each of us has a stronger arm and a stronger eye he believes the better arm should be at the top and the more gimlet eye nearer to the bowler. Given that most people are right handed and therefore have the strength on the right he finds it surprising that left handers are not more common. The impact of this minor imperfection was lessened in the brighter light overseas, and further reduced by the better backgrounds, thus in part explaining that distinctly lop-sided Test record. Barber himself is happy to agree with this; It was easier to bat outside England. Only Old Trafford of the English Test grounds had good sight screens. Lord’s, for example, had the red brick pavilion with just a small screen at one end and a dark tree-lined background at the Nursery End. On a typical dull English day batting there could be far from straightforward.

In addition there were other, rather less tangible, factors at work. Barber also readily acknowledges that he enjoyed the touring experience, and particularly the team spirit that Mike Smith’s captaincy created. The challenge of attempting to defeat Australia and South Africa in their own backyards, and the atmosphere created by the crowds he encountered are other aspects of touring that he looks back on with fond memories.

That slight issue with Barber’s eyesight certainly didn’t affect him as a youngster, and he scored runs and took wickets at Ruthin School as if in a totally different league from his peers. In 1954, whilst still at school, the 18 year old Barber was summoned to Old Trafford to make his First Class debut for Lancashire against Glamorgan. It might have been thought that the young man would have been encouraged to get to know his teammates, almost all of whom were seasoned professional cricketers. So in the 21st century it seems nothing short of bizarre to learn that when he arrived at the ground for a net the day before the match he was directed to the members’ sons net, rather than that of the men who he would be playing with the next day. This was despite the fact that his father was not a member! That said his unbeaten 41 contributed towards his county’s innings victory, so perhaps there was something to be said for what must have been the most gentle of introductions. That innings was to prove Barber’s highest score in nine games that summer, and he was barely called upon to bowl, but his cricket career was underway.

For the next three seasons Barber was at Cambridge University and did not play much for the county. He was of course, like all undergraduates, an amateur and when he finally played a full season for Lancashire in 1958, he remained one. He was an amateur in the classic manner, in that he derived no income from cricket. Combining that factor with the Public School followed by Oxbridge background has led many to assume that Barber was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. The reality is that that was far from the case.

It might have been different had Barber’s paternal grandfather not died in his forties. The fact that he did meant that Barber’s father, who had a won a scholarship to a grammar school, had to abandon his education in order to help to support his mother and sisters. He did so sufficiently well to enable his own son to complete the education he himself had had to leave unfinished. Armed with his degree Barber then gained a position with a relatively small public company that manufactured electrical switchgear. He was their first ever graduate management trainee, and their forbearance, coupled with the fact that until he got married in September 1961 he had no significant financial committments, allowed Barber to pursue his cricketing career. Looking back more than half a century he describes that job as …. a wonderfully helpful training for my later life.

Lancashire had a very traditional view about the distinction between amateur and professionals, and just eight years before Barber debuted, in 1946, had appointed Jack Fallows as captain, a man who had never played First Class cricket and, averaging just 8 for the season with the bat and not being a bowler, was patently not good enough as a player. He did however prove to be a shrewd and successful skipper.

After one season from Fallows Lancashire were fortunate enough to be able to appoint Ken Cranston for two summers. Cranston was a good enough all-rounder to play for England eight times in those two years, before his dental practice claimed him. Thereafter another true amateur, Nigel Howard, led the county for four years. In fact Howard also captained England, when a significantly understrength MCC side toured the sub-continent in 1951/52. In truth he wasn’t a Test standard batsman, but at county level he was sound enough, and he captained the Lancashire side well.

By 1954 his family textile business had claimed the 28 year old Howard and there was no amateur alternative so, as was happening increasingly in the county game, senior professional Cyril Washrook was appointed. Washbrook led the side for the rest of his career, but when the committee had to plan for the future in Washbrook’s final season they started by taking a backward glance towards the amateur ranks, and Barber, having occasionally deputised for Washbrook already was the obvious candidate. He took over in 1960. He was just 24.

One of the reasons why Barber was the favoured candidate will inevitably have been the events of a County Championship match at Cardiff in 1958. At 22 he found himself captaining the side due to an injury to Washbrook. Glamorgan were led by Wilf Wooller. His name is largely forgotten today but the 45 year old former Welsh Rugby Union international was an intimidating character. Cantankerous, combative and used to getting his own way he was Glamorgan cricket in those days. So worried was Washbrook about his young deputy being chewed up and spat out by Wooller that he decided to travel with the team. On the journey down there was just one piece of advice for Barber about dealing with his opposite number, repeated every few minutes throughout the journey; Whatever he says, you MUST disagree.

The first day of the game began with Wooller winning the toss and choosing to bowl. After Washbrook’s constant exhortations it was doubtless a good job that Barber kept it in the forefront of his mind that that was one of the things that the laws of the game did not permit him to disagree with Wooller about. After that it was a good day for the young skipper. He scored 48 at the top of the order and saw his side total 351 before Brian Statham and Roy Tattersall both made inroads into the Glamorgan batting. The hosts ended the day parlously placed at 5-3.

On the second day the rain bucketed down. In those days decisions over the weather were with the captains, the umpires only getting involved if they could not agree. Come the scheduled start there was no sign of Wooller approaching Barber so he went to the home dressing room to look for him. He was told by the Glamorgan players that Wooller was in his office outside the ground (he was the County’s secretary as well) so Barber sought him out there. It must have been with some trepidation that the young man pointed out to one of the biggest personalities in the game that between them they needed to make a decision. Wooller exploded, a heavily expurgated translation of his reaction being “Don’t be stupid, we cannot possibly play”. The ground was extremely wet, the sky looked like a piece of slate and it was still raining. Barber had no doubt but that Wooller was right but, with Washbrook’s words at the forefront of his mind, he disagreed. Wooller’s language again left something to be desired, but Barber stuck to his guns and, doubtless reasoning he had to eat anyway, Wooller agreed to come to the ground for lunch in due course.

His lunch consumed, and nothing much having changed outside, Wooller announced that he was going back to his office. Washbrook being present as well meant that even if Barber had been tempted not to lock horns with Wooller again he had little choice, so once more he steeled himself and disagreed. Over to the umpires, who then had a difficult dilemma, as they had no wish to bring themselves into conflict with either Wooller or Washbrook. The former England opener was nothing like as noisy as Wooller, and his language not as colourful, but that apart he was cut from not dissimilar cloth to the fiery Welshman. So they steered the only middle course open to them, and said they would make a final decision at tea, even though not a soul in the room would, if they were entirely honest, have believed there to be any prospect of play whatsoever.

At this point the players went to the cinema, about a third of the playing area being under water. While they were there the weather did a volte face, a strong wind blew, and by 5.30 they were out in the middle. When the day’s play ended the Glamorgan openers had played out three maiden overs. Their first innings had collapsed in a heap and they were all out for 26. It might have been 15, but their last man, left arm pace bowler Peter Gatehouse, one of only three men in the match who was younger than Barber, nicked a couple through the circle of close fielders. Wooller’s reaction is not recorded beyond the fact that he was, apparently, “furious”. Fortunately for him though, and sadly for Barber and Lancashire, no amount of disagreement the next day could prevent the rain having the last word, and the Glamorgan openers did not even have to resume their innings, but for Barber it was still a test passed with flying colours.

On assuming the full time appointment in 1960 Barber was, as a player, already established. The number of runs he had scored may not have been impressive by today’s standards; he had just scored 1,000 runs for the first time in 1959, averaged 36 and had only ever scored three centuries. But these were different times and Barber was as effective a batsman as any on Lancashire’s books. The most significant factor was the pitches. The variety of textures and preparations was much greater than today, and with wickets being left uncovered in a wet summer they would bear little resemblance to the sort of surfaces that 21st century county professionals play on. Spin bowlers could reap rich rewards on such surfaces, although for Barber’s part at this time he was just an occasional bowler, having taken only 40 wickets in his 93 First Class matches.

The Lancashire committee did not help Barber. In a manner which made a mockery of the oft-quoted justification for amateur captains, that being that they were free to stand up to their committees due to not being dependent on them for a living, they ordered the young skipper to stay at a different hotel from his men. In addition Barber, and any other amateurs who appeared, had a separate dressing room as well. This at least made some sense on one level. In Barber’s day the home and away dressing rooms were separated by a smaller room that was intended to permit the captain to have some privacy to speak to players, committeemen or indeed anyone else he might need to meet with. The reasoning did rather fall down though given that all amateurs had to share the room and that there was not also a space for the captain in the team’s room. Barber might have dug his heels in about the hotels, but the committee’s wishes were communicated to him by Colonel Leonard Green, one of the few who Barber respected, and a man who had captained the county in their 1920s heyday, so he acquiesced in the imposition of such feudal arrangements.

Despite this, although doubtless the committee would have believed because of it, Barber endeared himself to the county’s supporters by leading the side to a rare double over rivals Yorkshire in 1960 and, by August, the Red Rose was in touching distance of the County Championship. The last six games however were disappointing, and in the event even second place almost eluded them. The weather in Cardiff and Southport let them down, and Test calls for Brian Statham, Tom Greenhough and Geoff Pullar were a huge burden. Early on in that poor run in a match against Kent the opposing skipper, Colin Cowdrey, refused to go for a very fair target that was set and a tame draw resulted. Ken Grieves, Lancashire’s experienced Australian-born middle-order batsman, severely criticised Cowdrey in the press. Barber did no more than indicate to another journalist that he had some sympathy with his senior professional’s view, but it was Barber who was hauled over the coals and obliged by the committee to write a letter of apology to Cowdrey.

By this time Lancashire were a club in turmoil and players who should have been retained were allowed to go or forced to leave, and it was no surprise when the side fell to 13th in the table the following season. The committee decided a change of leadership was required. Barber’s own views on those who controlled Lancashire cricket in those days could fill a book, but in summary are The Committee was too large and had too many ‘experts’ who insisted on airing their views vociferously. There was little or no respect for players, and never once did a Committeeman suggest sharing a beer, wine, tea or coffee. Neither my views, nor indeed those of Ken Grieves or Brian Statham who followed me, were of any interest to them. As a captain at that time you took the blame for failure, which in those days was anything short of winning the only competition there was, the County Championship. Frustratingly however despite those expectations I could not do the things I believed in. I spoke and wrote about our need to develop and learn to be positive and so how to win, but too many minds wanted to pursue their own agendas. Winning the next match was everything, irrespective of how it might be achieved. The real frustration for Barber was the inability to force enough results. He was never happy with draws, but as he had warned the committee the absence of Alan Wharton at the top of the order (he had been allowed to go to Leicestershire where he enjoyed a fine season) seriously weakened the batting. It was the fault of nobody that an injury then robbed him for much of the season of Greenhough as well, but in a defensive era with two attacking options down and the Manchester weather to contend with the reality is that, as Barber succeeded in doing, winning more games than he lost was an achievement in itself.

The Committee’s public justifications for relieving Barber of the captaincy, were that it was hampering his development as an England player, and that he wasn’t bowling himself enough. The latter makes little sense, given that in 1960 Barber took 57 wickets at 24, and that he also had an England leg spinner, Greenhough, at his disposal. As to the former he had, somewhat unexpectedly, forced his way into the England twelve for the first Test against South Africa at Edgbaston in 1960. There was a widely held belief that the South African batsmen were vulnerable to wrist spin, largely as a result of the success that Johnny Wardle had enjoyed in the 1956/57 series when he decided to forego his normal orthodox slow left arm in favour of chinamen and googlies. Having been selected to play for MCC at Lord’s against the tourists, Barber troubled all their batsmen with his wrist spin, and it would have done him no harm when, shortly before the Edgbaston Test he put in a fine all-round performance in a County Championship match at the same ground.

There would have been few in the run-up to the Test who expected Barber to play, but the Edgbaston wicket was a slow one in those days, Kenny Barrington was in a poor run of form, and he was left out. Some sources say that it was Barber who took his place, but he had been told the previous day that he would be playing, and in fact it was Peter Walker who replaced Barrington. The South African born Walker could bowl seam or spin, was a serviceable bat and a magnificent close catcher. He got the nod following an inspection of the wicket shortly before the scheduled start. Barrington had played just a dozen Tests, and was mortified to be left out. He said tearfully to county colleague Mickey Stewart; “They’ll never be able to leave me out again. I’m going to see to that”, and the Barrington that came back for the next Test was even more the dour accumulator who England came to rely on so much over the next few years. England won comfortably, so Barber’s double failure with the bat mattered little, and although he bowled tidily enough, and took a wicket, England wanted another pace bowler at Lord’s. Three all-rounders had played at Edgbaston, and Ray Illingworth and Peter Walker had both done better than Barber, so he was left out.

Barber was not called on again in the South African series and he played no part in the 1961 Ashes. England’s selectors did not knock on his door again until the end of the 1961 season, so perhaps for once there was, irrespective of whether it was right or wrong, some justification for the Lancashire committee’s reasoning. Although a number of specialist batsmen and bowlers declined invitations to tour, Barber joined the party that played eight Tests in India and Pakistan in 1961/62 as a bowling all-rounder. He played in all the big games, performing reasonably well in India and, if without too much of a fanfare, with some distinction in Pakistan. During the tour an announcement came from Old Trafford that doubtless took Barber as much by surprise as the rest of English cricket. In the most reactionary move that even as conservative an organisation as the Lancashire committee could make a 34 year old Northern League player, Joe Blackledge, was plucked from his club side in the hope he would lead the county in 1962 with the same success that Fallows had enjoyed in 1946. The Uncle of future England Rugby Union skipper Bill Beaumont had at least played for the county’s second eleven in the past, and enjoyed a little more success with the bat than Fallows, but he proved unable to overcome the unhappy atmosphere that the committee’s actions had created, and Lancashire slipped to 16th in the table, their lowest ever position.

After his performances against Pakistan away from home Barber would have had high hopes of carrying on his Test career the following summer against the same opposition, and of then being in contention for a place in the England party that was due to try and regain the Ashes under Ted Dexter in the winter of 1962/63. For the first Test against Pakistan England made five changes, none surprising, as four first choice players, Statham, Trueman, Cowdrey and Graveney returned, as well as Barrington, who had missed the final Test in Pakistan. Barber wouldn’t necessarily have expected to play the whole home series, as it was unlikely England would choose to field three spinners, but given the fact that it was generally accepted that wrist spinners rather than finger spinners who succeeded in Australia, the expectation must have been that he would have been looked at again in what was not expected to be, and indeed did not prove to be, a taxing summer for England.

Was there a reason other than form for his omission? His performances with bat, and particularly ball had not been quite what they were in 1961 it is true, but the three off spinners that did tour Australia in 1962/63 was by definition lacking in variety and when, in the last Test of the series, England needed to bowl Australia out in the fourth innings to regain the urn the finger spinners never looked like doing the job, and indeed Dexter even tried a dozen overs of the part-time leg spin of Graveney and Barrington as he shuffled his pack on the final day – so he clearly knew what might have helped him.

The manager of the touring party to India and Pakistan was the former Essex captain Tom Pearce, and Barber himself wonders whether there may have been something in his end of tour report that counted against him. He had crossed swords with Pearce on several occasions. Barber did not like the manager’s lack of consideration for the players welfare, best exemplified by two contrasting but unpleasant personal experiences. The first was over leaving him in Pakistan without wallet, money, passport or plane ticket when the team flew to India whilst he had been sent to a social function at the end of the Lahore Test. The other was Pearce becoming agitated because an Indian doctor had taken Barber for an x-ray on a finger after Pearce had refused permission for him to do so. The net result was that Barber was expected to bowl leg spin with a broken second finger in the third Indian Test.

With the benefit of more than fifty years hindsight Barber recognises that some of his actions may have been unwise, but adds that I felt that as, other than captain Ted Dexter, who was often away, and Mike Smith, I was the only amateur and therefore as I did not have a tour bonus to lose as the pros had, that I should let the manager know my views. The tour manager would write a report after the tour and in those days the fate of the professionals’ bonuses largely turned on its contents. Amateurs were not therefore supposed to be the subject of such reports, although later events have caused Barber to believe that some adverse comments were almost certainly made, even if they weren’t recorded.

Moving forward Barber adds In 1962 I played in the Gents v Players match in July, a game that had some bearing upon the selection for the winter tour. On the Saturday evening the former Test batsman Willie Watson, who had fulfilled the roles of Assistant Manager, Vice-Captain and Senior Professional on a 1960 “A” tour to New Zealand that I had been a part of, and was now a selector, somewhat unusually asked me to come to dine with him. Over dinner he complimented me on my bowling but then told me that they were not able to consider me for the Ashes tour that winter. He did not say why – only “please stick at it, don’t give up”

Fabulous articles Martin, and great that he contributed so much!

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am GMT 5 November 2013

I remember we talked about him in the post-Hutton, pre-Gower English batting thread. I had looked him up then, and found him to be one of the most interesting cricketers in English history, especially so for the dreary 60s, as you mentioned. Really well written, Martin. Barber would have been quite the yang to Boycott’s boring yin. Alas.

Comment by harsh.skm | 12:00am GMT 5 November 2013