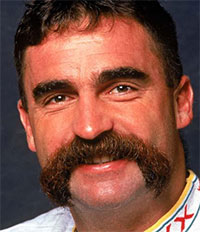

Merv

Martin Chandler |

Merv Hughes was 19 when he made his First Class debut, in a Sheffield Shield game for Victoria against South Australia in January 1982. His first delivery was a wide, although he recovered sufficiently from that to take three wickets in the innings, and ended the season with the respectable return of 18 wickets at 31.50.

The following year second season syndrome set in as Merv’s 11 wickets cost him nearly 55 runs each, and it was doubtless more indicative of the paucity of Australia’s resources at that time rather than his own performances that he was one of the three young Shield players to earn a cricketing scholarship to England for the 1983 season.

The early part of that 1983 season was cold and wet and eventually, rather than have the youngster idle, Essex arranged for Merv to play for Woodford Wells third eleven. Lavishly entertained by his teammates the evening before the game, and forced by his own forgetfulness to play in a pair of blue track suit bottoms, he looked anything like a future Test star. His first attempt at bowling resulted in him losing his footing on the damp surface and falling over. The next two were wides, to add insult to injury both going to the boundary. But this time there was no improvement, and when a wicketless Merv left Woodford Wells, having added a first ball duck to his cricketing CV, he must have feared a long and disappointing summer.

We found out very early that he just kept going whenever you asked him to bowl was Graham Gooch’s comment on Merv’s season in Essex, and he certainly stuck at his task, taking 60 wickets at 18 to head the second eleven averages by a distance. No one else took more than 16 wickets and even Neil Foster, who made his Test debut that summer, had an inferior average in second eleven cricket. In August Merv played once for the first team against the New Zealand tourists. He took six wickets, four more than any of his teammates.

By 1985/86 Merv was genuinely quick, and had caught the selectors’ eye, albeit his record was still hardly a great one, just one five-for from 24 matches. By this time Australian cricket was in a hole. A three Test home series against New Zealand in the November was lost thanks to some mercurial performances from Richard Hadlee, and when current incumbents Geoff Lawson and Dave Gilbert pulled out of the first Test against India in January 1986 with injuries Merv was called up.

At least Merv’s first delivery on his Test debut was a legal one, but that apart it was almost Woodford Wells thirds all over again. Merv did at least get a wicket, and in Dilip Vengsarkar a good one at that, but 1-123 was nothing to get excited about and that, coupled with a duck in his only innings, meant that a fit again Gilbert came straight back into the side for the second Test. Merv did get into the headlines after the first Test though, the issue being what he described as a bit of a discussion with Indian skipper Kapil Dev about how the latter’s bails became dislodged after an attemped hook. The wind was Kapil’s explanation, and the umpire could not gainsay that, but Merv certainly tried to.

In 1986/87 Australia lost to Mike Gatting’s England. Merv was consistency itself in the Shield, and played in four of the five Tests although his 10 wickets cost him 44.40 runs each. His worst memory was doubtless the Ashes record of 22 runs that Ian Botham took from one of his overs. He kept his place for the first Test against New Zealand the following year, but then lost it, first through having to give way to a second spinner and then through injury. He was back for a one-off Test against Sri Lanka, and recorded his first five wicket haul in that, but he was taken to task about his weight, which had been steadily increasing, and the selectors left him in Australia for the tour of Pakistan in September and October of 1988.

The shock of his omission prompted Merv to get fit, and the extra timber was gone by the time the West Indians arrived, but then his form deserted him and he missed the first Test of that series too. The second Test was scheduled for early December at the WACA, and he was back for that. At this stage Merv was 27, and his seven Tests had brought him 21 wickets at 37.71 apiece and, most definitely a tailender, he had scored a total of 44 runs at an average of 4.89.

West Indies had won the first Test comfortably. They did the same in the second Test as well, but no thanks to Merv, who finally arrived as Test match bowler. In their first innings West Indies, thanks largely to skipper Viv Richards and Gus Logie, totalled 449. Merv worked hard for his 5-130 in the course of which he dismissed Curtly Ambrose with the last ball of his penultimate over, and then with the first delivery of his next ended the innings by removing Patrick Patterson. Alan Border declared with Australia 54 runs behind and then Hughes, unbeknown to himself at the time, completed a hat trick by removing Gordon Greenidge with his opening salvo in the visitors reply. He ended up with what was to remain a career best 8-87, thus 13-217 in the match, but it did not prevent defeat. Perhaps drained by his efforts in Perth there was just a solitary wicket in the remaining three Tests of a series that Australia lost 3-1, although Merv did make a point in the final Test, an unbeaten 72 in the Australian first innings proving that he could wield the willow when he wanted to.

After their defeat by the world champions Australia travelled to England in 1989 seeking revenge for the indignities suffered at the hands of the Mother Country in 1985 and 1986/87. Despite starting the series with high hopes of holding on to the Ashes in the end England were flattered by their 4-0 defeat, as it could easily have been 6-0. After his lean spell against West Indies Merv had been expected to be behind Carl Rackemann for the third seamer’s job, but with the big Queenslander injured he started the first Test and for the second successive match recorded a half century and that, and his four wickets, made sure he played for the rest of the series. His role was not a starring one, but 19 wickets at 32 was solid support for the strike pair, Lawson and Terry Alderman. Australia had no further need of runs from Merv in that series, and indeed whilst in years to come he proved several times he could be a useful lower order batsman, in his remaining 41 Tests he never again made a Test match half century.

Like all his countrymen Merv revelled in that series of ignominious defeats that were handed out to England in 1989. As ever he was not short of aggression, and in the final Test was warned by umpire Dickie Bird for intimidatory bowling. Both Border and the press criticised Dickie for the warning, but Merv knew he had overstepped the mark, slipping in another bouncer almost immediately after he had been told not to overdo the short stuff.

In a one off Test against New Zealand and short home series against Sri Lanka and Pakistan in 1989/90 Merv was probably at his peak as a bowler, taking 34 wickets at a cost of less than 23 runs each in six Tests, and then it was the Ashes again, Australia starting the 1990/91 series as overwhelming favourites. It wasn’t too taxing a series for the home side, who won 3-0 and were never in danger. For Merv there were 15 wickets at 24.33 following a good performance in the last Test. Prior to that he hadn’t been wholly convincing, and had been made twelfth man in the third Test in order to give Rackemann an opportunity to impress. He didn’t take it, and Merv was back for the fourth match.

A few weeks after the Ashes the Australians visited the Caribbean for a clash between the world’s two best sides. The difference between the two teams was that the West Indies had four top class quick bowlers whereas Australia had just two, and Merv was somewhat inconsistent, so at times Craig McDermott was a lone spearhead. But Merv’s 19 wickets were a creditable haul, and the 31 runs he paid for each of them was a reasonable price.

The following season Australia’s visitors were India, and in a one-sided series the home side triumphed with a 4-0 scoreline. This time they did have four successful pace bowlers, and Merv was a vital part of it in taking 22 wickets at just 23. But it was a measure of the quality of the opposition that he was still behind McDermott, Reid and Mike Whitney in the series averages. There were just two wickets taken by Australian spinners in the entire series – one each to off spinner Peter Taylor, who played his last two Tests in the series, and one to Shane Warne, who played his first two.

The following year Merv was omitted from the party that toured Sri Lanka, most believing that his fitness was in question, but he was back for a last tilt at the West Indies a few weeks after the party returned, and apart from Tim May and Reid, both of whom played in only two Tests, he led the averages with 20 wickets at 21.60.

It was during this series that Merv first came into conflict with the then newly introduced ICC Code of Conduct. In fact he transgressed twice, in the first and last Tests. The first match looked like it would head for a draw, but then McDermott and Reid reduced the visitors to 9-4, and suddenly the win was there for the taking. But great champions don’t lie down easily and skipper Richie Richardson held the visitors innings together for a long time. Eventually Merv became so frustrated that following Steve Randell turning down yet another lbw appeal against Ian Bishop he asked him How come that was out yesterday, but not out today?

For Randell that amounted to an accusation of cheating, and he reported Merv to Match Referee Raman Subba Row. One contrite admission later and Merv lost 10% of his match fee, the lowest sanction available to Subba Row, who later said He (Hughes) came into the hearing and said ‘I said that, but you know me don’t you? I don’t bear any malice to anyone. I’m a bit of an idiot for doing that and I’m sorry’. It was in marked contrast to the conduct of his captain, summoned for a separate incident – AB simply didn’t turn up!

In the fifth Test Merv was reported again by Randell, this time for swearing. Again Merv admitted the allegation, but was adamant he was only swearing at himself. His reputation for honesty stood him in good stead. Subba Row accepted the explanation, and the matter was disposed of with a reprimand.

It had been a hugely frustrating series for Australia and the fact that tempers boiled over was hardly surprising. Australia could easily have won the first Test, took the second easily and comfortably drew the third. They then lost the fourth by just a single run, after the last wicket pair of Tim May and McDermott managed 40 of the 42 needed for victory. Only in the deciding fifth match did the men from the Caribbean look comfortable as they won by an innings and 25.

There was then further disappointment in New Zealand, where the hosts held Border’s men to a 1-1 draw in a three match series, before the 1993 Ashes campaign, which was to prove to be the last full series for Merv.

This time England did win a Test, but the scoreline in the six Test contest was still 4-1 to Australia. There had been hopes before the start that England might be able to compete on equal terms with Australia, in the bowling department at least, but it was not to be. Firstly Shane Warne delivered the ball of the century to Mike Gatting in the first Test and didn’t let the pressure drop all series, and secondly the pace attack, expected to be much reduced in potency by the absence of McDermott, was superbly led by Merv who took 31 wickets in the series at 27.25. In a summer that was perhaps more noted for the retirements of three modern greats, Ian Botham, David Gower and Vivian Richards, it was enough to make Merv one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year, along with fellow Aussies Warne, Ian Healy and David Boon, with a lone Welshman, Steve Watkin, the man who made England’s consolation victory possible.

With hindsight Merv should have called it a day after that success. In years gone by he would probably have had no choice. But the skill of his surgeon, together with his own determination to get back, meant that despite undergoing what proved to be a far from routine operation in September 1993 on the right knee that had been troubling him for some time he was fit, after missing home series against New Zealand and South Africa, for the reciprocal visit to South Africa in March 1994. An official Australian side had not visited the Cape for more than twenty years, the last occasion being when Ali Bacher’s dream team had finished off South African cricket’s Springbok era with a crushing 4-0 grand slam against Bill Lawry’s men.

Before looking at what happened in South Africa Merv’s on field persona needs to be examined. He was a hard-nut, well versed in traditional Australian mental disintegration techniques, and indeed plenty have said he could have written the book on those. Perhaps some of it started as a defence mechanism, as the way Merv bowled was a little eccentric to say the least. I have yet to see a better description of the way he played the game than appeared in Wisden in 1994; the mincing little steps leading to a stuttering run, the absurd stove-pipe trousers, the pre-bowl calisthenics, the whiskers, the silent-movie bad-guy theatrics. – at least by then the run up was a reasonable length – in his earliest days Merv was the sort of fast bowler who started out by gaining a bit of momentum by pushing off against the sightscreen.

Steve Waugh said of Merv He was the kind of guy that if he sniffed out a weakness. He would hone in and he wouldn’t let up. He was relentless. and no one would suggest other than that as a sledger he was a master, but was he as bad as he is sometimes painted? Possibly not.

The thoughts of three England captains who came up against Merv are interesting. Graham Gooch wrote Merv Hughes is thought to have invented sledging. But Merv is a cuddly baby compared to his predecessors like Rod Hogg, Dennis Lillee, Jeff Thomson and, especially, Len Pascoe. which hardly paints a picture of the traditional Merv image. But then whatever anyone thinks about him Merv was nobody’s fool, and didn’t believe in wasting energy any more than any other intelligent man. Gooch was well known as being impervious to sledging, so the likelihood is that Merv didn’t try too hard with him.

David Gower was and is so laid back that at times he seems completely unflappable. He too seems not to have been a target, and seems to have been untroubled by the more boorish of Merv’s antics describing him as fierce on the field but gentle off it, drawing a sharp distinction in that respect between Merv and Pascoe, who must have been quite a character.

Of course by the time Gooch and Gower first encountered Merv they were experienced internationals and older and wiser than the man they were facing. The final England skipper to face Merv was Michael Atherton, from a different generation. His first impressions of Merv were, there was no-one at all like Merv in county cricket, and he was a real eye-opener for me. There is no doubt that Merv did sledge Atherton hard, but even he accepted that he never really achieved a great deal. In 1993 he greeted him with In four years you’ve got no fucking better, to be met with the riposte and I see that in four years you haven’t got any new lines, Mr Hughes. As with Gooch and Gower sledging never bothered Atherton, but unlike with them Hughes did go on trying, but never claimed to have got any change out of his target. Perhaps it was just that Atherton’s always thoughtful rejoinders were something that he enjoyed. Only this year Merv has contributed to a book* and in it he comments on Atherton His sledging was always more subtle and intelligent than my basic stuff. It would often take me about three overs to understand what he meant. before, perhaps surprisingly, expressing the view If you wanted someone to bat for your life, you would give him a call.

Another man that Merv tried very hard to rile was Robin Smith, and this one was probably a draw. Before the pair first faced up to each other in 1989 Smith decided that he was going to stare Merv down and somehow news of that reached the Australians. The result was that Merv changed tack with The Judge, delivering his verbal fusillade at the end of his follow through and then immediately turning on his heels and walking back towards his mark without giving Smith any chance to make eye contact.

In the second Test Smith got his own back with one of the more famous exchanges in the encyclopaedia of sledging. You can’t fucking bat was Merv’s observation on a play and miss from Smith before, as per usual, he turned quickly away. The next delivery saw a trademark Smith square cut to the boundary and, quick as a flash, the comment We make a fine pair Merv. For once biting Merv demanded to know what Smith meant, the explanation forthcoming being I can’t fucking bat and you can’t fucking bowl. Merv did not see the funny side at the time.

For some however the sledging did work, most notably Graeme Hick**, Steve Waugh commenting Merv definitely won the battle with Hick and took him down. You could see it in Hick’s body language every time that he came on to bowl. Martin Crowe was another who let Merv get under his skin, his attitude to him being I would get so angry with what he was doing … to get me out was all the more galling because I had fallen into the trap.

To return to South Africa by now Merv was a veteran of 51 Tests. South Africa had drawn the series in Australia and the visitors desperately wanted to win the away series. In the event the home side won the First Test by 197 runs, despite being bowled on the first day for 251, and as their prospects of success receded the Australians discipline went with it. The trouble started with Warne, in South Africa’s second innings, letting Andrew Hudson have a stream of invective. Merv gave out plenty too, and was particularly severe on Gary Kirsten. Later he slammed his bat into an advertising hoarding close to the location of a South African supporter who was giving him a taste of his own medicine. The Match Referee, Englishman Donald Carr, imposed what amounted to a nominal fine – 1,000 Rand, the equivalent of GBP220 – doubtless hoping that the very fact of the fine would be sufficient. Warne and Merv were unlucky as the ACB just happened to be having a meeting as events unfolded, and they added a far from nominal GBP2,000 fine of their own.

The additional fine, coming as it did without the opportunity for Merv to state his case, broke all the rules of natural justice. The truth was that Merv had done nothing different to that which he had been so lauded for in the 1993 Ashes campaign, but he had failed to observe that, to use the words of Mr Zimmerman The times they are a-changin’.

Australia won the next Test to square the series. Shorn of his aggressive attitude Merv looked toothless. He failed to take a wicket and to rub salt in the wound was dismissed for a duck. It was his last Test, Reiffel replacing him for the final Test, an unsatisfactory draw to end an unhappy series that gave Alan Border anything but the send off he deserved after 156 Test caps.

At the start of the next domestic season in Australia Merv was only 33, and might well have harboured hopes of a return to the national selectors thoughts at some point, but it turned out to be his last season, a rather sad and unnecessarily public disagreement with Victoria skipper Dean Jones signalling the end. His final game, an innings defeat by South Australia, saw him return figures of 0-107, anything but a fitting way to end his career. There was a comeback of sorts, three years later, when he spent a couple of seasons playing List A matches for Australian Capital Territory. His figures were by no means poor, but by then he was not, understandably, quite the man he had once been.

*The Ashes : Match of My Life by Sam Pilger and Rob Wightman, published by Pitch Publishing

** The fact that Merv had the Indian sign on Hick seems to be generally accepted, and after playing in the first two Test of the 1993 series, and being dismissed three times by Merv, England dropped the Zimbabwean, before selecting him again for the final Test. Hick did however record a couple of half centuries, and averaged 42.66, against a career average of 31.32, so perhaps the “Merv effect” is overstated.

About 10 years ago, I went to a function where Merv was the speaker and he gave CA and young cricketers in Oz a massive spray

Every word has proven true

Quality bowler, top bloke, **** selector

Comment by social | 12:00am BST 23 July 2013

So much love for Merv. He was a superb bowler for us in the latter part of his career. Top piece as always mate

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am BST 23 July 2013

Good stuff. Even touching on his time at Essex. Excellent.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am BST 23 July 2013

I hasten to add that I watched him as a young teenager at Lord’s in 1993 (I think) and he played up to the group of us as we all told our stories about scary Merv Hughes, and he – standing right in front of us – turned around and shot us the Hughes stare and later a cheeky wink. What a legend.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am BST 23 July 2013

I like Merv but I’d rather we had bats the caliber of Law or Love to call on. They would walk into this Aussie lineup.

Comment by Tangles | 12:00am BST 24 July 2013

Merv did play for Woodford Wells. He played for the 1st XI most of the season and took a sackful of wickets at 9 a piece. Anyone that played with or against him will remember him, those that played with him rather more fondly.

Comment by Sean | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014