Gregory and McDonald, aka Fire and Brimstone

Martin Chandler |

The fact that the names “Gregory and McDonald” continue to be recognised by cricket enthusiasts, even those with limited knowledge of the history of the game is, looked at objectively, rather surprising. It is now more than 90 years since they last appeared together in a Test match, and even then their partnership consisted of just eleven Tests over a period of only ten months in 1921, eight against England and three against South Africa.

It is not as if their figures are particularly spectacular. McDonald’s 43 wickets came in 11 Tests and cost him more than 33 runs each. For Gregory there were 24 Tests which brought him 85 victims at 31. Neither man ever achieved a ten wicket match haul. McDonald’s strike rate was 67. At 65.6 Gregory’s was a little better but still a long way behind the 39.8 of current champion Dale Steyn. There is of course a lesson there about the value of statistics in judging the impact of cricketers – they may be an intricate tool with which to add the finishing touches to a player’s story, but they can never be the centrepiece.

Jack Gregory was born in 1895 and was therefore 25 when his Test career began. He had a fine cricketing pedigree. Syd Gregory, the famous Australian batsman of the previous generation, was his cousin. Two uncles, Dave and Ned, also played Test cricket and his father and another cousin graced the First Class game.

Ted McDonald was older and had celebrated his thirtieth birthday before making his Test debut. He was born in Tasmania for whom he made his First Class debut as a teenager. He subsequently moved to the mainland and played for Victoria, though there was not a great deal of top class cricket for him before the outbreak of the Great War.

So what sort of bowlers were these two legendary figures? For 21st century eyes there are a few celluloid fragments of Gregory in action but none, to the best of my knowledge, of McDonald. It is therefore necessary to look at what others have said of them.

The fearsome reputation was first forged in Australia during the baggygreenwash that was the 1920/21 Ashes series, although McDonald’s contribution in the three Tests in which he played was modest. It was the return series, in England in 1921, where the legend was set in stone. Writer Ronald Mason was a young lad in that far off summer, and fifty years on, heavily influenced by distant but still vivid childhood memories, he produced what remains the only English account of the tour.

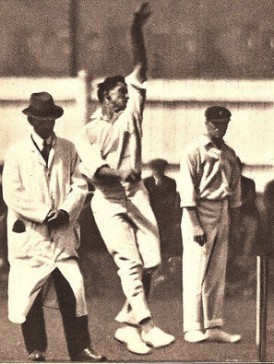

Of Gregory Mason said Jack Gregory was a tall rangy farmer with a beaky humerous face burned copper by the hot sun, an abounding energetic habit, and all the cricket talents enthusiastically displayed…. he took a fearsome bounding run to the wicket, flat out, rounding it off at the culmination with a quite frightening leap, which to the timid batsman facing him must have seemed well over stump high.

Moving on to his opening partner Mason continued Ted McDonald was in all respects except speed and physical destructiveness such a fascinating contrast to Gregory’s joyous extrovert energy …..tall, dark, withdrawn and contemplative; he glided easily without sound or weight along the curving line of a beautiful run-up, and uncoiled at its climax into a fluent languid action of captivating grace.

One man in an excellent position to describe what Gregory and McDonald were like is wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield who, with the Yorkshire-born undertaker Hanson “Sammy” Carter, shared the Australian keeping duties through 1921. He sets the scene by saying Gregory always had the advantage of bowling with the wind. I found McDonald’s approach to the wicket rhythmical and graceful by comparison to the bounding and somewhat ungainly run and delivery of Gregory.

Warming to his task Oldfield went on Gregory always swung the new ball more effectively than his teammate and he was , if anything, slightly faster while the sheen remained on the ball. Once the newness was worn off he relied wholly on pace whereas McDonald was able to turn the ball back from the off even at his fastest speed, and with this ball he could be most destructive. The spin that McDonald imparted added speed to his delivery in a most deceptive manner, after the ball made contact with the pitch. On the other hand, Gregory’s delivery did not gain pace from the pitch, rather did it lose impetus, particularly on a lifeless wicket..

Oldfield returned to his theme, once again on Gregory; His high deliveries, bounding run and controlled accuracy made him a dangerous and effective bowler. Using the new ball he swung it more disconcertingly than any other fast bowler to whom I ever kept wicket. His good length deliveries lifted awkwardly, as though they were short pitched, and so proved extremely troublesome to all types of batsmen., and on McDonald; Nothing in cricket was prettier than the action of McDonald. He bowled with such rhythm that his action seemed to flow as smoothly as a river. All his energy went into flinging the ball down and none into superfluous pounding of the earth or waving of the arms.

When considering which of the two were the faster bowler Oldfield’s conclusion was McDonald was, to my mind, faster than Gregory, though with a much lower action. He could always be relied upon, like Gregory, to keep a good, even perfect, length. He also assessed their respective merits overall I unhesitatingly hand the palm to McDonald as the greater because of his versatility and remarkable stamina.

For an English perspective I turn first to former Surrey captain Percy Fender. One of the shrewdest and most forward-thinking of cricket tacticians Fender faced the Australian pair in both Ashes series. Of the younger man Fender said Gregory is fast but it is not his pace that makes him difficult. He bowls a ball that turns occasionally, but it was not conscious spin that turns it – rather swing, “taking” off the pitch. Gregory’s great asset is the height from which he delivers the ball and the way he makes it get up, combined with his pace.

Fender was also positive in his comments on McDonald, which is significant given that his thoughts were published after the 1920/21 series and prior to McDonald’s great success in 1921. After being brought into the side for the final three tests, McDonald had the modest return of just six wickets at 65 runs each, and Fender’s summary of him confirms he had little luck; McDonald was, to my mind, faster than Gregory, though with a much lower action. He could always be relied upon, like Gregory, to keep a good, even perfect, length.

Next up is Lionel Tennyson. Unlike Fender the grandson of the illustrious poet, Alfred Lord Tennyson, was no great thinker about the game, nor indeed about anything other than how to live life to the full, but he was a decent batsman and more importantly a brave captain who led by example. Never was his courage more in evidence than in the Headingley Test of 1921 when, having been given the captaincy in an effort to instil some backbone into the England batting, he scored 63 and 36 to all intents and purposes one handed as a result of a fielding injury. In 1952 Tennyson wrote, ….. most of our batsmen had completely forgotten how to play fast bowling. The so-called “two-eyed” stance had taken the place of the old left shoulder forward, and left-foot-down-the-wicket style …. against that famous Australian pair, Gregory and McDonald, such methods proved hopeless. These two great Australians created an absolute panic., and later McDonald, with the exception of Sydney Barnes, I considered then to be the finest fast bowler I had ever seen. I still stick to that opinion, after seeing several of them, including Lindwall and Miller … Gregory was also better than the present Australian fast bowlers.

In his book Mason also visited the theme of the England batsmen’s fear of their opponents …it was Gregory and McDonald who shot away the tenuous foundations of any English courage and consistency that may have been there at the start; and in the serene recollections of half a century it is still the demonic image of this great pair of fast bowlers that rises instantly to the memory and rekindles the undying sense of apprehension. It is difficult to find words to express the demoralizing efficacy of this superb partnership.

Later on, and do remember he was writing in 1971, Mason attempted to compare the great fast bowling partnerships of his time. His conclusion was …I doubt if any of these were their equals in the immediacy and completeness of psychological effect. Thunder and lightening, hell and damnation, fire and slaughter – all these and similar kindred twin epiphets seemed sugar and spice in 1921 beside the bogey horrors of Gregory and McDonald

The views of Sir Donald Bradman are always worth considering particularly on players he played with and against. Gregory’s last Test was the Don’s first and he also played against him. He never played against McDonald in his early pomp but was one of his victims in 1930 when, on a sporting wicket at Aigburth, Lancashire shot out the touring Australians for just 115. Never a man to waste words of Gregory he said If ever a player could be termed vital and vehement it was Gregory. His bowling in the early days was positively violent in its intensity., and of McDonald, in the context of that match at AigburthIt was hard to visualise a more beautiful action which, coupled with splendid control and real pace, made him the most feared bowler in England at that time.

No survey of descriptive writing about players of this era would be complete without reference to Sir Neville Cardus for whom McDonald was a great favourite. Of his great hero there are many descriptions but my two favourites are Ted McDonald was the most beautiful and on his day the most satanically destructive of fast bowlers. He ran to the wicket so silently that Leonard Braund said that, when he was umpiring, he could hear the approach of McDonald only by the rustling of his shirt. and later I cannot find language yet to describe the awe-inspiring and mingled speed, power and effortlessness of his attack. Rhythmic, tawny, acquiline. The silent curving run of McDonald. Stumps flying like spears. It was bowling of havoc but also of rare beauty. It was bowling which seemed to become ignited from the burning sun above.

The great scribe was also an admirer of Gregory and, in the course of the obituary that he wrote in Wisden, the by then veteran Cardus wrote As a fast bowler, people of today who never saw him will get a fair idea of his presence and method if they have seen Wes Hall, the West Indian. Gregory, a giant of superb physique, ran some twenty yards to release the ball with a high step at a gallop, then, at the moment of delivery, a huge leap, a great wave of energy breaking at the crest, and a follow-through nearly to the batsman’s doorstep.

The consensus amongst their contemporaries seems to be that McDonald was the greater bowler, with one notable exception. Harold Larwood, who knew a bit about bowling fast, said of the pair, in an autobiography published in 1965, Jack Gregory I nominate as the greatest among the Australian fast bowlers. There was little to choose between him and Ted MacDonald in regard to speed but I think Gregory was just a little ahead of his great opening partner because he was a man of more terrifying appearance.

As to which of the two was the greater cricketer opinions generally shifted, unsurprisingly, because Gregory was much more than just a fast bowler. He was a left handed batsman who eschewed the protection of batting gloves and, generally, anything that might be interpreted as defensive batting. The high watermark of his batting came in that 1920/21 series when he recorded a century and four fifties and averaged 73.66. In the series in South African that followed the 1921 Ashes he scored what remains to this day, in terms of time, the fastest Test century ever recorded, in just 70 minutes.

That fast scoring record is not the only one that is still the property of Jack Gregory. He also had a prehensile pair of hands in the slips and no fieldsman has ever equalled, let alone bettered, the 15 catches he held in 1920/21.

Is it because of, or despite the brevity of their time at the top that the story of Gregory and McDonald has held such a fascination down the years? I suspect it may be the former, although any consideration of their later careers begs speculation as to what their reputations might now be had they, for example, enjoyed the longevity of Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller.

For Gregory there was a cartilage operation in 1922 which was not, in those days, the straightforward procedure it subsequently became. It cannot have been an uncomplicated recovery as Gregory did not appear in First Class cricket again until Arthur Gilligan’s MCC team arrived for the 1924/25 Ashes. He appeared in all five Tests of the series. His batting was nothing like as effective as it had been in 1920/21 but with the ball he took 22 wickets, and although he paid 37 runs each for them, it should not be forgotten that these were timeless Tests. England lost 4-1 but Herbert Sutcliffe averaged more than 80, Jack Hobbs more than 60, and five other Englishmen more than 30.

In 1926 Gregory made the trip to England and once again played in all five Tests. Again his batting was disappointing but so too this time was his bowling, just three wickets at fractionally less than 100 each being no sort of return for a Test match pace bowler. Despite that setback the big-hearted Gregory, still only 33 years of age, was in the Australian side for the first Test of the 1928/29 Ashes series. He had removed Sutcliffe, Wally Hammond and England captain Percy Chapman at a personal cost of 142 when his career ended. A young Larwood was enjoying himself on his way to 70 when he misjudged the pace of a Gregory delivery and a possible caught and bowled opportunity popped up off his glove. Gregory went for the catch and fell awkwardly on his dodgy knee. He knew instantly that his cricket career was over. He could neither bowl again or bat in a match that England won by the small matter of 675 runs.

As for McDonald he opted for the financial security offered to him whilst in England in 1921 by Nelson of the Lancashire League, and he was back in England for the 1922 season. He made his debut for the Lancashire county side in 1924 and between 1925 and 1930 he enjoyed a run of remarkable success with the Red Rose County. Four times in those six seasons Lancashire were Champions and in the other two were second and third. Only twice had they taken the title in the previous 35 years, and only twice have they done so in the subsequent 81. Small wonder that to this day McDonald is so revered to the west of the Pennines.

After leaving the First Class game McDonald went back to the leagues before becoming the landlord of the Raikes Hotel in Blackpool, at which point he played occasionally as an amateur for the town’s ambitious Ribblesdale League side. In the early hours of 22 July 1937 MacDonald was driving home from a charity match when he saw a fellow motorist who had broken down. Despite his mephistophelian reputation, and indeed appearance, McDonald was a man of generous spirit and stopped his own car a little further on. He got out and was walking back to assist when he was struck by another vehicle and killed. He was 46.

McDonald never wrote a book, and although I believe his biography has been written it has never been published. Gregory, following a journalist misquoting him in 1928, always shunned the press and no doubt the comparative lack of information about the pair has also helped to build up the air of mystery, and consequently fascination, that surrounds them. The indefatigable David Frith did eventually get away with presenting himself at the front door of the then 77 year old widower Gregory. It was as well that he did as the great man passed away the following year. The result of the conversation was a delightful interview that appeared in the May 1972 edition of The Cricketer and which, for those who do not have that and have no desire to scour the second hand market for a copy, also found its way into Frith on Cricket, published last year by Great Northern Books.

Really enjoyed that read, thanks mate.

Shame there’s so little on McDonald. I’d read Bradman’s thoughts on him previously. I’d wondered if there was any suggestion his action in any way influenced Larwood, so we might have some idea as to what he looked like as he bowled, but there doesn’t seem to be any suggestion he did.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 3 December 2011

First opening pair of quicks in test cricket weren’t they? I remember reading somewhere that they caused a fair bit of upset over here due to their bowling being rather more intimidating than what had gone before. Perhaps an inspiration for Jardine 10 years later?

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 4 December 2011

Terrific piece Martin.

Comment by zaremba | 12:00am GMT 4 December 2011

Ray Robinson rated Gregory and MacDonald a little behind Larwood (on his own at No.1) for pace and in front of Constantine, Farnes, Lindwall and Miller etc. I would have to check I do believe I have a DVD with with some video of 1921 and MacDonald and Gegory. Gregory looks very awkward and MacDonald smooth but in the old Newsreel looks languid and it is hard to believe he is bowling fast. Joe DB

Comment by Joe Drake-Brockman | 12:00am GMT 4 December 2011

Another wonderful piece Martin. 🙂

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am GMT 7 December 2011

Michael Holding was called ‘whispering death’ and ‘the Rolls-Royce of fast bowlers’ because of his smooth, almost noiseless run-up and delivery. McDonald and Holding sound very much alike.

Comment by JOYDEEP SIRCAR | 12:00am BST 21 July 2013