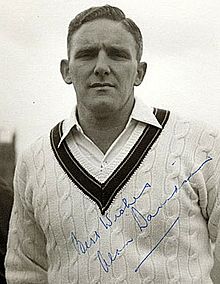

Davo

Martin Chandler |

Of those who have completed their Test careers since 1945 only two men, Englishmen Frank Tyson and Johnny Wardle, have paid less for their wickets than Alan Davidson. In Wardle’s case the difference is marginal, 20.37 as against 20.53. For Tyson there is a rather greater gulf, The Typhoon having paid just 18.36 for his victims. It should however be borne in mind that neither Englishman, particularly Tyson, played anything like the number of Test of Davidson, that neither ever played Tests on the sub-continent let alone flourished there, and also that most of Davidson’s best performances came a few years later, when the laws, pitch preparation and prevailing attitudes amongst coaches and administrators meant that the delicate balance between bat and ball had started to tip back towards those who wield the willow.

The oddest feature of Davidson’s record is that his early Tests, in that era in the mid 1950s when so many bowlers, Tyson and Wardle included, did so well, were most certainly the weaker part of his career. His first 12 Tests brought him just 16 wickets at the unremarkable average of 34.06 and, for a man who was always regarded as an all-rounder, albeit a bowling one, just 317 runs at the distinctly ordinary average of 18.64 with just a solitary half century and one other innings greater than 23. It was only in 1957/58 in South Africa, by which time he was already 28, that Davidson found the form that catapulted him to the very top, and where he was to remain for the next five years until his all too early retirement. The 32 further Tests that constitute part two of his career brought Davidson 170 wickets at 19.25, and he scored a further thousand runs at a much more respectable 27 with four more half centuries and several other important contributions down the order.

The most surprising thing about Davidson, to me anyway, is just how a man who Richie Benaud has described as … one of the greatest cricketers ever to set foot on a ground for Australia has generally been overlooked in any discussions I hear about the great fast bowlers. Quite why that should be the case is, on reflection, easy to explain and no doubt confined to the northern hemisphere. Not unnaturally during my formative years as a cricket lover my interest in past Ashes series was focussed largely on those of 1953, 1954/55 and 1956 when England were dominant. Davidson played a role in all three series, and a very modest one too, sowing the seeds of a belief that he was a less than outstanding cricketer. His Ashes glory days came later, in 1958/59, 1961 and 1962/63, none of which series were, from an English perspective, memorable and which, like the rather longer period between 1989 and 2005, I tend to skate over.

The young Davidson started out as an unorthodox left arm spinner but when he was 17, thankfully for Australia, circumstances conspired to turn him into a pace bowler. His club captain took Davidson to one side to give him some batting practice and, after a time, asked him to speed up for a bit of variation. Davo shattered the skipper’s stumps and although nothing was said at the time, the following day as the match began he was thrown the new ball and told to get on with it. He took four wickets in his new style and was a whirlyman no longer.

Davidson bowled and batted left handed. That in itself is not so unusual, even if it does happen rather less frequently than might be expected, but what verges on the bizarre is that he wrote with his right hand, was a right-handed tennis player and a right-footed footballer. As a bowler he was distinctly brisk, without being genuinely fast. He generally bowled over the wicket to the right-hander, pushing the ball across him but initially, as Trevor Bailey observed after his first Ashes series in 1953, ..his bowling was accurate rather than devastating.

As a batsman he was, in an era when many observed a strictly safety first policy, an aggressive strokeplayer with a penchant for hitting sixes on the off side – silly mid off and short cover were never places to be when Davo was batting. His never having recorded a Test century does of course take a gloss off his status as an all-rounder, but no less an authority than Sir Donald Bradman once wrote I emphasise how great a batsman Alan might have been had not bowling taken so much of his energy, and I cannot think of any all-round player at any time whose absence from the Australian XI was of more importance

To complete the all-round package Davidson was a superb fielder whether close to the wicket or in the deep. His reflexes were such that he was known as The Claw so well known was his ability to pluck the most improbable catches out of the air. An example was in the final Test of the 1956 series when, with England already assured of holding onto the Ashes, a half-fit Denis Compton was recalled to the side after surgery on that famous knee to play what was to prove to be his final home Test. It was a glorious farewell as Compo top-scored in England’s first innings with 94. The old warhorse couldn’t buy a run for the first quarter of an hour of his innings, and his old friends Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller gave him a torrid time but, to the delight of the nation he got over his sticky start and moved serenely towards what would have been as emotional a century as English cricket has ever seen. He got to 94 when Ron Archer strayed a little down the leg side and Compton sent it off the meat of the bat down to fine leg for four, or at least he thought he had, until he saw that the ball was actually reposing snugly in Davidson’s capacious hands at backward square leg. Part of the value of Davidson in the field was that wherever his captain put him he could be certain that in the batsman’s mind that was not going to be an area where he looked to play the ball.

As an outfielder Davidson’s name was made right at the beginning of his career. He was just 20 when he toured New Zealand with what was effectively an Australia second XI. There was one country game on this tour where he famously took 10-29 and then followed that up with an unbeaten 157 in less than three hours, although as not one of the opposition ever played a First Class match it is difficult to gauge how strong they might have been. That much conceded as the batting had been reduced to 218-5 before Davidson got to the crease in the Australian innings, the bowling at least must have been of a reasonable standard. More pertinently that tour is remembered for an occasion when, and here of course the strength of the opposition is irrelevant, he ran a batsman out with a direct hit from the boundary, with just a single stump to aim at. His reputation went before him after that, and countless good runs were not taken over the years as batsmen were not prepared to take the slightest liberty with The Claw.

Such was Davidson’s contribution to the 1953 Ashes series that despite playing in all five Tests all Australia’s leading scribe, former Test opener Jack Fingleton, found to say about him in his summary was to praise his fielding. He had taken just eight wickets, although in fairness to him he had done his job. He was, after all, just the fourth seamer after Lindwall, Miller and Bill Johnston, and the ball seldom had much shine on it when he got hold of it – his accuracy was such that he still went for less than two runs an over. As for his batting he only had 182 runs to show for his ten visits to the crease, although 76 came at Lord’s in the Australian first innings. As many as 58 came in boundaries and he scored those runs out of 117 added for the last five wickets. Had he not scored those runs England would almost certainly have won, and Bailey and Willie Watson would not now be remembered for their remarkable rearguard action.

When Frank Tyson and Brian Statham propelled Len Hutton’s side to their 3-1 triumph in 1954/55 injuries restricted Davidson to only three Tests and he, as he missed Australia’s thumping innings victory in the first Test, had a thoroughly miserable time with bat and ball averaging just 14 with the willow and his three wickets costing 73 runs each. It was not however lost on the English batsmen that in the final Test, with an extra yard of pace and having finally got his hands on a ball with most of its shine left on, he looked a much more dangerous bowler. But an enjoyable Ashes series still eluded him as he didn’t have a much better time in 1956, Jim Laker’s year, when the spin-friendly pitches didn’t help him, and a chipped bone meant he only played in two Tests anyway. Eight runs and two wickets are a tally best forgotten.

In 1957/58 Australia visited South Africa, who had done very well in going down 3-2 to England in 1955 and holding them at home the previous winter. Given England’s then dominance over Australia, and the fact that Lindwall, Miller and Johnston were all gone, it was felt the Australians would struggle. In fact they won 3-0. Davidson was the main strike bowler and he took 25 wickets at 17. Time and again he took out the South African top order leaving wrist spinners Benaud and Lindsay Kline to clear up the later batting. There was not much need for runs from him, although in the fourth Test his side were looking rocky at 234-7 when he came out to join Benaud – they were 315-8 when he left after a quickfire 62, and went on to a ten wicket victory.

The difference for Davidson was having the new ball. He had learnt how to swing the ball into the right hander late and with that to complement his natural away swing he had become a matchwinner. His action was a model for left arm bowlers with an easy relaxed approach to the wicket with a gradual acceleration into his delivery stride. His run-up was always a metronomic fifteen paces, the title he chose for his 1963 autobiography.

The significance of that South African series was probably lost on England as they prepared to defend the Ashes in 1958/59. The MCC assembled what on paper must be the most formidable side ever to leave England, and confidence was high that the Ashes would be retained. They weren’t however, and in fact it was a 4-0 drubbing. Peter May’s men were routed by the illegal bowling of Ian Meckiff, Gordon Rorke, Keith Slater and Jim Burke – surely it was nothing to do with the aging English superstars being outplayed by a new youthful Australia, skilfully led by Benaud, or 24 wickets from Davo at 19, or his important contributions with the bat in the third and fourth Tests?

Of course expectations were that Davidson would be caught out the following winter. Eight Tests in the unforgiving heat of the sub-continent was surely going to be enough to render him impotent again? Touring conditions in Asia were poor in those days, and most of the tourists were ill at least some of the time, and Gavin Stevens came close to losing his life. Davidson clearly had his doubts as he sounded out Bradman about missing the trip, but was informed that his Test career may not have a future if he was not available. In the end the man who had a reputation for picking up niggling injuries on what seemed like a match by match basis actually managed to avoid the worst excesses of the various maladies that his teammates endured. He did however have to put up with the exhaustion of bowling long spells as he was the only Australian pace bowler to have any real impact taking 41 wickets across the eight Tests at just 18 runs each. Meckiff, with 15 at 35, was a long way back. Australia won both series.

The following Australian season saw what remains one of the greatest Test matches, in one of the greatest series, and Davidson’s career reached its apogee. At the Gabba Australia famously tied with Frank Worrell’s West Indians. Davidson the bowler took 11 wickets for 222 and if that were not enough he scored 44 in the first innings and, before being run out as part of the frenetic denoument, his highest ever Test score of 80 in the second. Even Davo couldn’t continue at quite that rate, but despite missing the fourth Test through injury he still recorded his highest series aggregates with both ball (33 wickets at 18.54) and bat (212 at 30.28).

In 1961 Australia came to England and, for the first time since Bradman’s Invincibles had done so, won. It was testament to Benaud’s captaincy that a side as weak as any Australia had sent to these shores triumphed 2-1. The only top class bowlers were the skipper and Davidson, and of the batsman only Harvey had a proven track record in England. With 23 wickets at 24 Davidson was Australia’s leading bowler by a distance and once again there was a decisive role for him that he is not remembered for, at Old Trafford as Australia won the fourth Test to retain the Ashes and cement Benaud’s position in the minds of the English cricket-loving public as one of the great captains. Australia conceded a first innings lead of 167 and were just 119 runs on with four wickets to fall when Davidson came out to the middle. A little later it was a lead of 157 with the last pair at the crease. Davo and Graham McKenzie then put on 98. There were ten fours and two sixes in Davidson’s innings as he spectacularly threw off the shackles that Gloucestershire off-spinner David Allen had imposed. Allen’s final figures were a mightily impressive 38-25-58-4. Before Davo launched the partnership with 20 from one of his overs they were little short of remarkable. It wasn’t that the pitch stopped taking spin, as Benaud later showed, it was just that Davidson bullied Allen out of the attack. England needed 256 to win, and got to 150 with only Davidson’s dismissal of Noddy Pullar in the debit column. Then Benaud took his 6-70, before Davo fittingly took the last wicket to clinch a famous victory.

And that was almost it for Davidson. There was no Test series for Australia in 1961/62 so it was a last hurrah against the old enemy in 1962/63 before, still only 33, he slipped out of the game and into the business world where he remained for the rest of his working life. It is true that he had lost just a little of his zip, and that the long history of niggling injuries were taking their toll, but he was still an outstanding bowler. Australia retained the Ashes courtesy of a 1-1 draw but England were a strong batting side with Kenny Barrington averaging 72, Ted Dexter 48 and Colin Cowdrey 43. Top of the Australian bowling averages for the series sat one AK Davidson with 24 wickets at a cost of exactly 20 runs apiece – a distant second was another fine fast bowler, McKenzie, with 20 wickets at nearly 31. The man who took a wicket with his last delivery in Test cricket, and had done the same a month earlier when he bowled Gary Sobers with his final delivery in the Sheffield Shield, left a huge hole for the Australian selectors to fill.

[QUOTE]The young Davidson started out as an unorthodox left arm spinner but when he was 17, thankfully for Australia, circumstances conspired to turn him into a pace bowler. His club captain took Davidson to one side to give him some batting practice and, after a time, asked him to speed up for a bit of variation. Davo shattered the skipper’s stumps and although nothing was said at the time, the following day as the match began he was thrown the new ball and told to get on with it. He took four wickets in his new style and was a whirlyman no longer.[/QUOTE]

Haha that is such a great, classic old cricket story.

[I]”Get on with it.”[/I]

Comment by Prince EWS | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

Nice article and a good read.

Comment by Himannv | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

Made my day reading that, Davidson :wub:

Comment by Jager | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

I do remember reading somewhere that his bowling of Sobers was with ‘Irish’ swing, a ball that came back in the great man alarmingly, ricocheted off his pads as he played back and took leg stump – perhaps a skill of Davidson’s that has gone almost completely undocumented

Comment by Jager | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

Absolutely loved it.

Thanks for this Fred

Davo, so so under rated.

He definitely has a case to be included ahead of McG in the AT Aus XI

Davo :wub:

Comment by smalishah84 | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

Great read.

What a grand cricketer he was. He’s also one of nature’s true gentlemen, and should be mandatory fare as a guest speaker. He’s a legend.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 1 November 2012

Great piece on an often overlooked cricketer – I was wondering though what was your criterion for that first sentence, given that neither Tyson or Wardle took 100 wickets.

Comment by stumpski | 12:00am GMT 3 November 2012