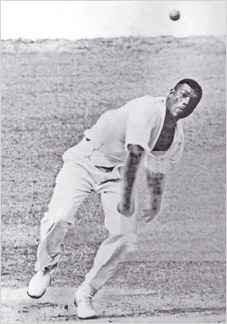

Charlie Griffith – Guilty or Not Guilty?

Martin Chandler |

Barbados is not a large island, just over 160 square miles and a population, in the 1950s, of less than a quarter of a million. The parishes of St Michael and St Lucey are, more or less, at opposite points of the country but despite that there were occasions in the middle of that decade, when Wesley Hall and Charlie Griffith were growing up, when the two played on the same side. Within a decade they had become one of the most potent pairs of fast bowlers ever unleashed. As teenagers though Griffith was an off spinner, and he relied on Hall for his reactions behind the stumps, rather than to soften up the batsmen for him.

Hall was a year older than Griffiths, and made his First Class debut at 18 in 1956. Griffith was somewhat older at 21 when he first appeared almost four years later, and he made a remarkable start. The match was for Barbados against the touring MCC side of 1959/60. The home side batted first and piled up 533-5 before Everton Weekes declared on the second afternoon. Before long England were 23-3, and Griffith had sent back three England skippers, Colin Cowdrey, Mike Smith and Peter May. Later on he added Kenny Barrington to his haul and, as England followed on, he added another captain, Ted Dexter, as well as removing Smith again.

That was all for the time being but, with England leading the series 1-0, the West Indies selectors decided three months later that Griffith’s second First Class match would be the final Test. Unfortunately in the interim he had let his fitness go somewhat, and although he made an early breakthrough when he had Geoff Pullar caught at slip with England on 19 he had no further success, and his disappointing match return was 1-102. To make matters worse England comfortably secured the draw they needed to win the series. There seems to have been no controversy about the Griffith action, the respected English writer EW ‘Jim’ Swanton, describing him as some six feet three, with a high arm and bounding follow-through.

India visited the Caribbean between February and April of 1962. Since his Test debut Griffith had played just three more First Class matches, and was not included in the side for the first two Tests against the Indians, both won convincingly by West Indies. He no doubt looked to the Barbados match to stake his claim for a place in the remaining three. In fact it proved to be a match he would prefer to forget, a frightening incident involving Indian captain Nari Contractor being the cause.

In simple terms a Griffith delivery struck Contractor on the temple, fracturing his skull. It was touch and go for a time, but the skill of his surgeon ensured Contractor would survive. He did play First Class cricket again but he had played his final Test. More than half a century on Contractor is still with us and will be 81 this year. The entire cricket world grieved when Philip Hughes died last December. One suspects that the former Indian skipper will have felt the pain rather more acutely than most.

What happened? With no television pictures we need to look at the accounts of the participants. There is no unanimity. Griffith’s famous partner, Wes Hall, wrote later He (Contractor) got behind a ball from Charlie, intending to push it towards short leg, completely misjudged the kick, bent back from the waist in a desperate last second bid to avoid it and was hit just above the right ear.Hall went on It had not been a vicious ball, never rising above the height of the stumps and concluded Griff was in absolutely no way to blame. In his own autobiography Griffith described the delivery as being bail height but given that he also described having already dismissed Vijay Manjrekar at this point his recollection is undoubtedly unreliable.

The height of the delivery is where the controversy arises. According to Garry Sobers he had to tell Griffith not to appeal for lbw. Griffith himself suggested it was wicketkeeper David Allan who was ready to appeal. In 2002 Sobers wrote that Contractor ducked into a ball that didn’t get up. The Indians disagreed. Farokh Engineer was adamant the delivery was a bouncer. The man who replaced Contractor as skipper, Pataudi Jnr, acknowledged that his captain ducked into the ball, but wrote that the ball started at neck height, so Contractor didn’t duck far. Erapelli Prasanna was not so dogmatic, writing that he didn’t believe the delivery was a bouncer, but he certainly didn’t suggest that he agreed with Hall’s account.

According to Wisden, certainly a neutral reporter, Contractor did not duck into the ball. He got behind it to play at it. He probably wanted to fend it away towards short-leg, but could not judge the height to which it would fly, bent back from the waist in a desperate, split-second attempt to avoid it and was hit just above the right ear. Exactly what happened matters little but, given that all those I have mentioned were doubtless being honest in their recollections, it is interesting to see the different perspectives put on the delivery by the two teams.

Immediately after he was struck Contractor was dismissive of those who ran to his assistance and shaped as though he intended to bat on. A slightly delayed outpouring of blood from the ear and nose put a stop to that idea, and he was quickly helped from the field. Further blood was spilt shortly afterwards when another Griffith bouncer broke Manjrekar’s nose causing him to retire hurt having scored just two. The Indians eighth and last wicket fell at 86, and they conceded a first innings lead of 308. Following on they were soon 56-4 but they managed to save the game. Manjrekar showed particular courage as he remained unbeaten at the end on exactly 100.

In the second innings Griffith cut down his pace and didn’t bowl any bouncers, something that is confirmed by Pataudi. Against that background it seemed bizarre then and now that during that second innings the man rated then as the best umpire in the Caribbean, Cortez Jordan, who had umpired Griffith many times before, called him once from square leg for throwing. Griffith was so upset he could barely concentrate. Barbados’ stand in skipper Conrad Hunte left him bowling on the basis that would at least give him something else to think about, and the legality of his action was not questioned further. The hostility of the crowd towards Jordan and Griffith slowing down to something like medium pace might have accounted for that, but what is certain is that there were to be many occasions in years to come when Jordan umpired Griffith at Test and First Class level, and he never called him again.

What did the great Frank Worrell think of Griffith? Sadly he did not live long enough to write the autobiography that might have told us, and we are left with some contradictory evidence. More than one of the Indians have said that prior to the Barbados game Worrell warned them that Griffith threw and, in a very slim biography, Ivo Tennant tells us that the reason Griffith did not play in any of the Tests against India was because Worrell wouldn’t have a thrower in his team. If that is true then by 1963 something must have happened to change Worrell’s mind. In addition Worrell was quick to jump to his bowler’s defence when Richie Benaud criticised Griffith in 1964/65. Tennant’s far from convincing explanation for that is that Worrell only pitched in to that argument because of what he considered Benaud’s hypocrisy over the throwing issue given the dubious record in that department that Australia had in the late 1950s.

Everton Weekes was Griffith’s captain in the Barbados team. He missed the Indian game but when he got pack he supported his man, saying I have not found him to be a chucker. His bouncer is so good that some say that he delivers it with a dubious action, but he certainly does not break the law because he does not bend his arm. In view of his position at that time Weekes was hardly likely to openly criticise Griffith any more than any other West Indian. There is a rather unsatisfactory Weekes autobiography form 2007, Mastering the Craft, in which he mentions Griffith only fleetingly, but despite having the opportunity to do so, and one of the few things he did do was point out Griffith’s ability to suddenly produce a much faster delivery, he did not question the legality of his action then either, so it seems likely that he did believe what he said back in the early 1960s.

There was no more First Class cricket for Griffith between the match against India and the announcement of the side to tour England in 1963 that was announced in September 1962. Having been ignored for the Indian series Griffith was genuinely surprised to be included. Worrell’s side lit up the game in England in much the same way that the 1950 West Indians had done and Griffith had a magnificent summer. In the Tests he took 32 wickets at 16.21 and on the tour as a whole 119 at just 12.83. West Indies ran out comfortable 3-1 winners.

Sadly for Griffith however the summer was not all sweetness and light. After the fourth Test the murmers about his action became widespread and culminated in a controversial newspaper column written by England captain Ted Dexter that spelt out the accusation and described the series as meaningless as a result of it. In fact all of the major England batsmen of the time have always maintained that Griffith threw, and the problems that Kenny Barrington had with him are particularly well known. But not everyone agreed.

In his summary of the tour for The Cricketer John Arlott wrote Griffith was the matchwinner. His action is not beyond query, but it passed some stern English umpires. He was a constant menace. Keith Miller, writing in the Daily Express was more forthright; I reckon Griffith has a magnificent action that many youngsters might usefully try to copy.

More interesting for those who believed that the umpires in 1963 were told by Lord’s not to call Griffiths was a televised discussion between Dexter and former Test match umpire Dai Davies. The discussion took place in 1965. Film of Griffith was shown and Davies’ view, not accepted by Dexter, was Most West Indians have a flick of the wrist and so has Charlie Griffith, but at the point of delivery his arm is straight.

In the 1960s former Surrey and England fast bowler Alf Gover was the leading coach in the world and ran a well known indoor school in London. Gover took a Commonwealth side to Pakistan in 1963/64 and Griffith was a member of his team. So he had a good look at the controversial action. Gover was convinced that Griffith’s basic action was fine, but he had no doubt that he threw his yorker and bouncer. The problem that Griffith caused batsmen was that those two deliveries, his quicker ones, were yards faster than his standard delivery, yet there was no difference in his approach to the wicket. The change came when he opened his chest, his body fell away to the left and in Gover’s words From that position he cannot bowl the ball, he must throw.

In 1964/65 the Australians made their second trip to the Caribbean and, for the first time, lost a series against the West Indians. Griffith was not so devastating as he had been in England, but 15 wickets at 32.00 were a significant contribution to the victory. Like the English team before them the Australians were convinced to a man that Griffith threw. Richie Benaud was particularly outspoken and the dust jacket of the book he wrote on the series consisted of side by side photographs of Hall and Griffith that were intended to illustrate his point.

Benaud also quoted fellow Australian and respected First Class umpire in England Cec Pepper at some length, including extracts from correspondence passing between Pepper and the MCC regarding the Griffith action, which Pepper was convinced was illegal. What Benaud did not do is explain why, when writing in the News of the World in 1963, he had at that point expressed the view that the Griffith action was fair.

Had Benaud spoken to Fred Trueman before writing his book he would have garnered more evidence for his conspiracy theory. During the Lord’s Test of 1963 Trueman was on his own in the dressing room enjoying a long soak. His presence clearly not obvious he overheard a conversation between former Middlesex and England all-rounder Walter Robins, then chairman of selectors, and the two umpires Syd Buller and Eddie Phillipson. According to Trueman Robins was issuing a very firm instruction to both men not to no-ball Griffith for throwing. He said nothing immediately, but later recounted the story in one of his autobiographies – the tale was, much to the Yorkshireman’s irritation, vehemently denied, but ‘Fiery Fred’ always maintained it was true. It must of course be probable that Fred’s version of events lacked some context, but it is undoubtedly consistent with what happened, or rather didn’t happen.

By 1966 West Indies were the strongest side in the game and they underlined that when they visited England that summer. The public were distracted by the FIFA World Cup that took place at the same time, but those that were interested in the cricket saw the visitors win three of the first four Tests before, Brian Close having been recalled to captain England, there was a remarkable turnaround in fortune in the fifth Test when England, after slumping to 166-7, then recovered to 527 and an innings victory.

Griffith was not as effective as in 1963, his 14 wickets at 31.28 putting him behind Hall, Sobers and Lance Gibbs in the Test averages. The general perception was that he was being careful, and losing some of the extra speed on the bouncer and yorker. In an early season game at Old Trafford he was, for the second and final time, called for throwing by Arthur Fagg, although the episode was something of a damp squib. He had already been called several times for overstepping and initially the press missed the incident. There was a suggestion this was because Fred Jakeman, the umpire at the bowler’s end, had called another front foot no ball simultaneously, although that seems not to be correct. I have also read that it was Fagg himself who contacted the press to confirm what had actually happened. More likely to be correct is the comment in Wisden that it was the Lancashire side who alerted the press, although the one member of the Lancashire team that day that I have spoken to had to confess that he simply couldn’t recall the incident..

The series was not a happy one for Griffith. During the second Test extracts from Dexter’s forthcoming autobiography were given to the press and the former England captain’s allegations against Griffith were foremost amongst the matters featured. Then at Trent Bridge Griffith was severely criticised for striking Derek Underwood on the head with a bouncer. ‘Deadly’ was making his Test debut and was batting last, although at the time of the incident he was putting up the sort of dogged resistance that he was to become known for as his career progressed. At Headingley Griffith produced one of his really quick bumpers and ‘Long Tom’ Graveney only just managed to get out of the way. Umpire Charlie Elliott told Griffith, and his captain Sobers, in no certain terms that he wasn’t happy with the delivery, and that if it was repeated Griffith would be called.

West Indies next Test action was in India in December of 1966. They won a short three Test series 2-0 but the fabled pace attack was not the reason. Hall played in all three Tests but the lingering effect of a knee injury reduced his effectiveness and his 8 wickets cost him 33.25 runs each. Griffith took 9 wickets at a marginally better average than his partner, but was described by Wisden as neither impressive nor terrifying. The tour was covered in little more than a sentence in Griffith’s 1970 autobiography, Chucked Around.

The following year saw an English visit to the Caribbean, and England repeated their success of 1959/60 thanks to Garry Sobers’ infamous declaration in the fourth Test. Griffith’s series average, before he broke down injured in that fourth Test, was 23.20, well ahead of any of the other specialist bowlers. But there were only 10 wickets, six of them tail-enders. Despite his outwardly unwavering belief in his innocence it seems Griffith must have taken some note of what was said about him given that Wisden’s bold explanation of his much reduced effectiveness in 1967/68 was Griffith as a straight arm bowler was never in the highest class.

Griffith has always vigorously denied all allegations of throwing. Whilst he has no choice but to accept that there were plenty of images of a bent arm he countered that, in 1991, by echoing Dai Davies and saying my arm was bent during the delivery swing but straightened before release, which does sound perilously close to a ‘jerk’, a word that was to disappear from the then Law 26 after Griffith retired, but which was there throughout his career.

One of the consequences of never having played the game to a decent standard is that I struggle with some of the more technical aspects of the game and this is a classic example. I raised this subject with a former Test batsman who I think I will leave anonymous on this occasion, and he nailed the point instantly; Try to throw a ball as hard as you can and see whether, after the ball has been released, the arm is straight – can you throw it hard but finish with an arm which is not straight? The same gentleman provided another interesting insight, and an explanation for all of Griffith’s greatest critics being right handers; Charlie bowled from very wide to start with, and leaned out further to his left so that the incoming angle was even greater. Either it came as a yorker or as a bouncer, and that was rarely a wasted over the head bouncer, it was a throat ball. Consequently he was far more difficult for a right hander to play than a left hander. For lefties his stock ball was often lovely for driving, and his bouncer more dangerous to his slips than the batsman.

Although he was just 30 Griffith’s Test career came to an end the following year when he toured Australia and New Zealand. West Indies won the first Test but lost the five Test series. Griffith played in three of the Tests but managed only 8 wickets for which he paid more than 50 runs each. He was still embroiled in controversy though, as he was the man in control in the fourth Test when the international game saw its second mankading. The batsman concerned was Ian Redpath. The Australians were looking for quick runs, and there was no warning given. At the next interval West Indies skipper Garry Sobers went into the Australian dressing room and apologised. As Australia ended up 20 short of victory with their last pair at the crease it may have been a crucial move. The Australian crowd were, unsurprisingly, incensed at Griffith’s action. But in the press it was notable that men like Tiger O’Reilly and Keith Miller, neither of whom would surely have contemplated doing the same thing, both came out in favour of Griffith.

For some time the working title of this feature was Big Bad Charlie, but as I researched it I realised that there is a little more to Charlie Griffith than the way he was portrayed by men like Kenny Barrington and Ted Dexter. He is often described as moody and taciturn but, as Sobers wrote in 2002 he was seriously affected by the strength of criticism and withdrew even further into his shell before adding pointedly that he was one of the greatest fast bowlers ever produced in the West Indies and one of the most abused.

In 1966 John Clarke penned a book on that summer’s series and made a particularly telling comment; No one thought about what effects the anti-Griffith campaign, mainly run by players and ex-players, was having on the man himself. All I knew was that before the tour got underway he was affable, but once the first “Griffith is a chucker” headline went up he always looked the other way. It must have worried him as, unlike many other top cricketers, Griffith has only cricket to depend on for a job.

The truth is that few in the early 1960s did Griffith any favours at all. He should have been taken out of the game and handed over to the likes of Alf Gover to sort him out. As it was the differing views of the appeasers in the corridors of power on the one hand, and on the other those on the field, both players and umpires, who sought to have the game played fairly, left Griffith in a state of perpetual anxiety, always waiting for the next incident. All things considered I can fully understand why Griffith bared his teeth from time to time, no one should have to undergo a career long trial in an unregulated court of public opinion, but that is exactly what Griffith had to put up with.

In fact there was a thoroughly decent and sensitive man underneath the hard exterior. Griffith was deeply upset by the Contractor incident, and visited the Indian skipper each day that he was in hospital. The manner in which his long running feud with Kenny Barrington ended does him great credit too. In the first Test in 1967/68, whilst backing up, Barrington somehow managed to strike Griffith’s neck with his elbow during his follow through to send him crashing to the ground. The umpires must have been dreading what was going to happen next, but Kenny was the first, apologising profusely, to go to Griffith’s assistance. If Griffith had given Kenny, already a centurion that day, a right hook, he would have had considerable mitigation. As it was he took the apology in the spirit it was given and half a decade’s mutual antipathy evaporated in an instant.

Griffith made a success of his life after cricket, becoming a sales manager with and ultimately a director of a Barbados lumber company. He remained remarkably fit, and came to England to play in some end of season exhibition matches at the Oval in 1982. In 1990, aged 51, he was back again with a club side, forming a handy looking attack with Wayne Daniel (34) and Joel Garner (37). Much later, in 2007, a Mumbai based journalist caught up with Griffith and got an interview with him, although many of the questions came from the interviewee, asking after Nari Contractor and expressing his pleasure at hearing the former Indian skipper was in good health. The summary, as it reads, avoids the throwing issue, which is a great shame. In the autumn of his years it would be interesting to know whether Charlie Griffith still feels as unfairly traduced as he did when Chucked Around was published back in 1970.

“From that position he cannot bowl, he must throw”. Rohan Kanhai came to the opposite conclusion: (1) From that position one cannot chuck abouncer because a chuck would skid; and (2) From that position it is difficult to chuck a yorker because the chuck will be erratic. I am more inclined to accept Kanhai’s version.

Comment by Arjun Tan | 7:56pm GMT 6 March 2016

I watched the entire second day of the Barbados – India game in 1962 from a seat in the back row on top of the sight screen, pavilion end, within 3 feet of the wicket line. I have a few observations I would like to add.

1.Griffiths bowled a short ball to Contractor (half tracker) and expected a bouncer. It didn’t bounce and Contractor ducked in anticipation, paused, hesitated and was hit around the right temple.

2. The ball that felled Mandjrekar was a typical Griffiths extra-fast one – delivered from well outside off with a huge body-lean to the left and a “flexed: elbow”. It was a huge off-cutter pitching about 18 inches outside off. Mandjrekar appeared to be letting it go when it jagged back towards his groin. I think the ball came off the shoulder of the bat, hit him in the face (?nose) and rococheted to Hall at short leg at speed. Hall never got his hands to the ball and was hit in the face and needed treatment. A dropped catch!

3. Griffiths was called for throwing in the second innings against Nadkarni when bowling from the Pavilion end. Nadkani batted left-handed so the umpire was at point. From that direction, it was always easier to see the bent elbow because Griffiths typically delivered with his body arched to the left so his head did not impede the umpire’s view.

Comment by Roy Low | 1:41am GMT 7 January 2017