The Greatest All-Round Performance?

Martin Chandler |

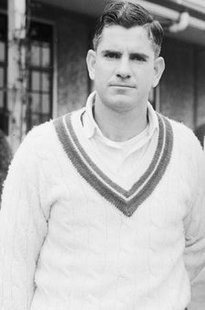

By the mid 1950s the momentum in the Caribbean islands to throw off the shackles of Colonial rule was building, and with it the resentment caused by the fact that no black cricketer, save George Headley once, had ever been appointed captain of West Indies. It had seemed that the times were changing in 1953/54 when Worrell was appointed as Jeff Stollmeyer’s deputy for the England series, but just 12 months later that job was taken from him and given to Atkinson.

Skipper Stollmeyer, who had no part in the discussions that gave rise to the vice-captaincy being changed, later described it as a preposterous decision and the cause of much of the dissension and bad cricket played by our team in the series. Walcott’s somewhat scathing comment in his autobiography was Atkinson took over even though the three Ws were in the team and he was fulsome in his praise for the efforts of Clairmonte Depeiza in the fourth Test, whilst pointedly not commenting on Atkinson’s performance. Weekes’ comment was similar, to the effect that Worrell’s demotion was felt by most people to be part of the ongoing refusal to give Frank the respect that was due to him.. Weekes at least conceded that Atkinson had a decent game in the fouth Test, but clearly aligned himself with the outraged majority.

Stollmeyer injured his hand during practice and missed the first Test, so the job of skippering the side fell to Atkinson. The match was lost by nine wickets. As the game was in progress the United African National Council arranged for a loudspeaker car to drive around the ground proclaiming their disgust over the appointment of Atkinson. For the second Test Stollmeyer was back but, in a move hardly likely to do anything for Atkinson’s confidence, the vice-captain was left out of the side this time. Australia still dominated, but thanks to a century in each innings from Walcott, and Weekes coming within 13 runs of replicating his achievement, a draw was comfortably secured.

Atkinson was back for the third Test, although few noticed above the furore brought about by the dropping of Smith, Ramadhin and Valentine. The later recall of Ramadhin shortly before the game began, on the face of it due to the view being taken that the wicket would turn, did nothing for the selectors credibility. This time, in the only low scoring game of the series, Australia’s winning margin was eight wickets. Atkinson achieved little with the bat, but he was his side’s best bowler. West Indies were playing four spinners. With a match haul of 4-117 he took the most wickets, and bowled more overs than anyone else.

Whilst fielding in the brief Australian second innings Stollmeyer had fallen and damaged his shoulder, so he was out again for the fourth Test and Atkinson was thrust forward again on his home island. The decision was again deeply unpopular, particularly in Jamaica where the final Test was due to be played. Another nationalistic organisation, The African Welfare League, protested vociferously in Jamaica, and sent a telegram to Atkinson that read The sporting public of Jamaica demand you to be decent enough to step down from the captaincy in favour of Worrell.

To add to his woes Atkinson lost the toss, and Johnson had first use of an excellent batting wicket. It was not until after lunch on the third day that Australia were all out, and they totalled 668. Their pace bowling trio were the backbone of the innings, with centuries for Lindwall and Miller, and Archer failing by just two runs to emulate them. At the top of the order Les Favell and Harvey posted half centuries, as did wicketkeeper Gil Langley, batting at 10. It was his only Test fifty. Atkinson shuffled his pack, using eight bowlers altogether. He himself bowled most of all, 48 overs, and went for only 108. He took the wickets of Lindwall and Favell.

The first problem to confront Atkinson was what to do about his opening partnership. He was in a tricky situation as he only had one recognised opener and he, John Holt, was in no sort of form. When the side had been selected it had been assumed Holt’s partner would be Depeiza. The wicketkeeper was not a top order batsman, but he had made a gritty half century from the top of the order in Barbados’ recent game against the tourists. He had however just spent more than two days concentrating behind the stumps, so Atkinson decided to give the job to Sobers. Playing just his fourth Test Sobers had yet to pass fifty, but he had always had an excellent relationship with Atkinson, and was happy to oblige. The Lion of Cricket proceeded to hit Miller for seven fours in his first three overs. It couldn’t and didn’t last, but he scored a very rapid 43, all but three of them in boundaries.

The Ws and Smith came and went and the close was still some way distant when, at 147-6, Depeiza came to the crease to join his captain. They averted further disaster and added 40 runs before the day’s play ended with the home side on 187-6. Atkinson was on 19 and Depeiza 22. After them all that was left between West Indies and an ignominious defeat were Ramadhin, Valentine and Dewdney, career batting averages 8.20, 4.70 and 2.42 respectively.

The local population wouldn’t, understandably, have expected very much out of the next day’s play, so only around 4,400 of them were in the ground. It turned out to be one of those sporting occasions when many more than actually witnessed an event later claimed to have been there. The beleaguered captain and “The Leaning Tower”, as Depeiza was affectionately known due to his trademark forward defensive stroke where bat and pad went forward together and remained in situ for a good couple of seconds after the shot was completed, batted all day. Only once before had two batsmen, Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe, batted through a full day of Test cricket without being parted.

The fourth day started well enough for the home side, but Australia would have expected the new ball, taken at 207-6, to achieve the breakthrough. In the event though the pair were totally unfazed, the most telling observation on the subject being one would hardly have known it had been taken, so brightly and briskly did Atkinson attend to it.As the pacemen gave way to the spinners the scoring rate slowed, neither man prepared to take any risk, but it was a quiet morning for ‘keeper Langley – Atkinson was on 68 before a delivery, from Johnson, beat his bat.

At lunch West Indies were 282-6, with Atkinson on 95 and Depeiza now on 37, rather different from the opening of the day when Depeiza was slightly ahead. When Atkinson duly went to three figures after lunch he had scored 103 out of 148, in 130 minutes. Both batsmen went serenely on without offering the bowlers much in the way of hope. There was one occasion when Benaud howled in anguish as Depeiza chose to leave a leg break that only just passed over the stumps, and had he been quicker on his feet there was one straight drive from Atkinson that he might have got a hand to, but it was 365-6 when the first chance came. After a mix up between the batsmen Atkinson, by then on 147, should have been run out, but Langley made a hash of an uncharacteristically wayward throw from Harvey, and he got home in the nick of time.

So desperate did Johnson become that, after just 17 overs in 32 Tests, he tried Harvey’s occasional off spin for four overs. He even gave Watson one over, a man whose bowling career was so neglible (just 46 wicketless deliveries in all) that neither cricinfo nor cricketarchive records the style in which he bowled. Tea came with the score 417-6, Atkinson 185 and Depeiza 78. Another new ball arrived at 427 and finally some joy for Miller as Atkinson’s cover drive found its way into Benaud’s safe hands. Sadly for Australia however it was a no ball. Whether or not Atkinson heard the call and altered his shot accordingly I have not been able to establish, but in those days of the back foot no ball law he might well have done.

As Depeiza approached his century Miller upped his pace, and at one point unleashed three successive bumpers to stop the leaning tower coming forward. The West Indies ‘keeper took it all in his stride however, and soon afterwards a steer to the boundary past gully took him to his century, and the partnership passed 300. That pressure relieved Depeiza had a brief rush of blood to the head and cover drove Miller for four, bringing up the 450 mark for his side.

Approaching his 200 Atkinson was by now beginning to tire, and at 195 he drove Lindwall to McDonald at mid off, but the chance went down. Depeiza tried to take more of the strike after that and Atkinson’s progress slowed. He was stuck on 199 for what must have seemed to him like a long time, and he was doubtless much relieved to finally get the single. It was a rare false shot, an inside edge to fine leg off Lindwall, but that hardly mattered. The next target was 344, the previous best partnership ever recorded for the seventh wicket in First Class cricket, a record that was 53 years old. The pair got their with ten minutes to go, and after that stubbornly defended for the rest of the session. The next target was 344, the previous best partnership ever recorded for the seventh wicket in First Class cricket, a record that was 53 years old. The pair got there with ten minutes to go, and after that stubbornly defended for the rest of the session. They went in on 494-6, with just 25 more needed to avoid the follow on. The dynamics of the game had changed dramatically from 24 hours previously.

After the enthralling cricket of the fourth day the fifth began in anticlimactic fashion as Depeiza was dismissed by Benaud without addition to the overnight score, and then 10 runs later Atkinson’s innings ended on 219 at the hands of his opposite number Johnson. Ramadhin and Dewdney were quickly spun out and West Indies were all out for 510. That was still 9 short of avoiding the follow-on, but with a sixth day being played Johnson chose to bat again.

Les Favell added an aggressive 53 to his first innings 72 but two more wickets fell quickly after his and at last it seemed that the wicket was beginning to deteriorate. There was a strong wind blowing the dust around, and in combination with the glare coming off the typical shiny Caribbean wicket batting conditions were not easy, but with a first innings lead of 158 the Australians weren’t unduly troubled by the variable bounce and turn that the West Indies spinners were able to extract and would have been happy enough with their close of play score of 184 for 8. Watson, Miller, Archer and Lindwall had fallen to Atkinson. Most seemed to believe that Miller had got an edge on the delivery that the umpire decided was out lbw, but there was no doubt that Atkinson bowled very well. Next morning he completed his five-fer, but Australia got to 249 and with a lead of 407 there were only two possible results, the draw or another Australian victory.

Atkinson had, as he had in the first innings, bowled more overs than anyone else, 36 of them, 16 of which were maidens and his return was 5-56. Smith, 3-71 in 34 overs was the other main contributor, and Sobers nipped out Benaud in his 14 overs. Ramadhin and Valentine bowled just 8 overs between them, a remarkable fall from grace for two men who, barely half a decade earlier, had tormented a decent English batting side in their own backyard.

When Holt and Sobers walked out to begin the fourth innings there were 230 minutes of play left. For 200 of those minutes there was little drama. The Australians set attacking fields, and the home side lost wickets regularly, but Holt made 49, and Walcott 83, and the last half hour begun with just five wickets down and Atkinson and Smith at the crease. Then there was a moment of controversy. Miller, doubtless bearing in mind how little batting there was to follow, decided that he wanted one last burst at the home side, and he wanted a new ball with which to do it. Wise to that one the West Indies, 193-5, stopped scoring (playing conditions were that a new ball was due after 200 runs). So two Miller deliveries were allowed to go for four byes each and Miller attacked with a classic “Carmody” field, three slips, two gullies, leg slip, and two short legs. Smith succumbed to Lindwall but in a brief reprise of their first innings heroics Atkinson and Depeiza made sure that the tail was not exposed as they ended up on 20 and 11 respectively.

His 122 in the first innings was Clairmonte Depeiza’s only First Class century. Although only 28 at the time his last First Class match was in 1956, when he left the Caribbean to pursue his cricketing career in the leagues in England and Scotland. For Denis Atkinson there were another 8 Tests over a couple of years, but he never came close to repeating the magnificent captain’s performance he produced at Kensington Oval in 1955, a match that deserves to be remembered much more frequently than it is.

Great article as usual Fred.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am BST 25 July 2014

Top work as always, mate

Comment by bagapath | 12:00am BST 26 July 2014

Public service broadcasting at its finest. More the fulfilling CW’s educational remit.

Seriously, great stuff. A chap who, one admits shamefacedly, I never heard of until now. A wonderfully un-Caribbean name, Denis Atkinson. More fitting for a pre-war Burnley wing-half.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am BST 27 July 2014

I think your cricrate All Rounder rankings puts far too high of a benefit on runs and not enough on wickets.

Comment by Blocky | 12:00am BST 27 July 2014

GREAT MEMORY! Brought back by a superb Great article! MANY THANKS.

Denis is my uncle and I was at the game (12 yrs old) in the George Challenor stand next to the players Pavillion.

Also, had the privilege as a young boy of meeting all the players!

Comment by Charles Atkinson | 10:26pm GMT 16 December 2023