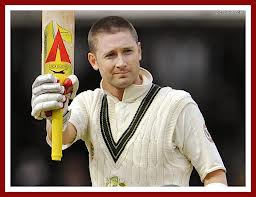

Can Clarke Emulate Border?

Gareth Bland |

During the recent four Test series between India and Australia, Greg Chappell pondered on the jewel in the Australian batting crown, the captain, Michael Clarke. Why, asked Chappell, could Clarke not best his predecessor, Ricky Ponting, and go on to amass in excess of 13,000 Test match runs? Fine player though Clarke is: technically adroit, wristy and with the economy of movement that only the best possess, it is not, perhaps, the first question that Australian fans will be asking themselves of their captain as his team attempts to surmount the not inconsiderable challenge presented by Alastair Cook’s England side in the coming months.

In the year that the Ashes go into overdrive – not to mention potential overkill – with back-to-back series, rarely has an Australian captain faced such a challenge. In invoking Clarke’s immediate predecessor, Ponting, Greg Chappell overlooked a more apposite turning point surrounding the leadership of the team some twenty eight years ago. In 1985 Allan Border returned home from an Ashes series with a husk of an Australian team in his wake. Australia was a team that needed rebuilding, rebooting and reviving in order to survive the remainder of that decade and go on to dominate the next one. It is in Border’s situation that we find circumstances most similar to those faced by Clarke today.

Border had inherited the captaincy in November 1984 following Kim Hughes emotional collapse. Initially hesitant and loath to administer the kind of authority and discipline that had defined the Chappell eras, Border was ably assisted in his empire building by coach Bobby Simpson and three other revolutionaries. Recognising 1985 as being Australian cricket’s modern anus horribilis the then chairman of selectors was Simpson’s former state team-mate Lawrie Sawle. A seer, Sawle identified an initial group of sixteen players whom he believed should be groomed for the top. In the cricket academy, “Bacchus” himself, Rodney Marsh, developed the young talent earmarked for international honours, paving the way for a conveyor belt of star graduates. To top off the group came the team’s physiotherapist, Errol Alcott, a man who would become to Australia what his compatriot, Dennis Waight, had become to West Indies. Sawle’s chairmanship, in unison with the spirit engendered by Simpson, Marsh and Border, was summarised by Gideon Haigh as “a commitment to the common weal”. For too long, Simpson felt, Australian cricket had been characterised by self-interest. In order to be the best, and beat the best, that clearly had to change.

Results initially matched Border’s morale, despite the captain’s own unimpeachable form with the bat. In the Australian summer of 1985/86 the skipper seriously considered quitting his post on more than one occasion; the strain and the inability to reverse the trend of defeat seemed too much. In 1986/87, prior to England’s arrival for Ashes battle, Australia toured India and participated in an entertaining series, culminating in the tied Test in Chennai. It was in the subsequent Ashes series that Border’s new Australia reached their nadir, however, bottomed out and began their ascent to the top. Arriving in Sydney 2-0 down the young team pulled off a thrilling victory to restore pride as well as giving the series result a more palatable gloss.

The team which had been mercilessly mocked, the one that had opened the first Test with a seam attack comprising a grand total of eight caps, and had seen veteran quick Geoff Lawson likened to an old race horse in need of being reduced to glue in the second, had come up with the goods at last. The likes of Steve Waugh, Geoff Marsh, Boon, Bruce Reid and Merv Hughes had all grown up together as a unit. A year on and a grinning, bearded Border would raise the Reliance World Cup aloft in India after his team defeated England in a close run game in Kolkota. From that point their stranglehold on the Ashes would become absolute, too. Not until 2005 would they be surrendered and even then England’s tenure was shockingly brief.

If the task was a difficult one for AB almost three decades ago, then it is surely even tougher for Michael Clarke now. Of a similar age when they ascended to the captaincy, Border was 29 while Clarke was 30, each had been a junior member in a champion, if fading, team. While Border started out sharing a dressing room with the Chappells, Lillee, Marsh, Hughes, Thomson, Mallett and Laird, after his debut under Yallop the previous winter in 1978/79, so Clarke arrived as the freshman in a team of giants the likes of which the modern game has rarely bettered. English eyes first fell upon him as the youngest member of a batting line-up which comprised Hayden, Langer, Ponting, Martyn, Gilchrist and Katich during the 2005 Ashes summer. The great side’s last gasp was to pulverise the visiting Englishmen in 2006/07 5-0: the emphatic nature of the thrashing was perhaps matched by the one-by-one nature of the retirements from the team in the wake of reclaiming the Ashes. It was a domino effect that Australian cricket has since shown no sign of being able to recover from; a precipitous decline matching that of West Indies during the 1990s.

And so Michael Clarke heads towards this summer’s Ashes series and beyond with a collection of players hailed by Gaurav Gupta in The Times of India as “the worst Australian team ever to visit India”. With Ponting gone and with Michael Hussey now also retired, Clarke is the lone batsman of undoubted world-class in the side. Tellingly, in the 13 Tests Australia played in the past year, 7 of the 11 individual centuries came via the blades of Clarke and Hussey. Moreover, in the recent India series three of the top six batsmen averaged fewer than 20, while the experienced Shane Watson had a notably poor time with the bat. Concerns over the side’s inability to buckle down and graft with the bat are compounded by doubts about the bowling personnel and the management style of the team coach.

In the spin department Glenn Maxwell has demonstrated promise as an off-breaking all-rounder, while Nathan Lyon, Xavier Doherty and Steve Smith have yet to consistently demonstrate the kind of class needed at the top level. In terms of pace, Clarke’s outfit looks raw to say the least. Doug Bollinger and James Pattinson were both dropped in India, while both Mitchell Starc and Peter Siddle disappointed. Mitchell Johnson, with 54 caps, remains the most experienced – and sharpest – of the quicks on offer.

Off the field the episode which in years to come may yet become known as Homework-gate, is indicative of a management style thought not in tune with the younger players. The coach, Mickey Arthur, perhaps too keen to wield the stick, scolded Shane Watson, Usman Khawaja, Pattinson and Mitchell Johnson for their submission of “reports” on the opposition in a manner which was seen as too tardy by half by the South African. Risible though it may seem, such apparent lack of unity cannot bode well for the young team’s chances and the lifting of the burden on Clarke.

The apparent ease with which former captain Ricky Ponting topped the averages in domestic competition does not suggest a surfeit of options available to the Australian captain and his selectors. Concerns about the paucity of batting talent have been openly expressed by chairman of selectors, John Inverarity, as his squad of 20 centrally contracted players contains just 6 specialist batsman. Of these, only one, Clarke, averages in excess of 50, while the next best, Phil Hughes, does not exceed one of 40. How often during that tour of India must Clarke have cherished his days of being “Pup”, of being the greenhorn surrounded by baggy capped grandees in Ponting’s champion team of yore.

Michael Clarke’s task in rejuvenating one of Test cricket’s greatest powers is without parallel in recent Australian cricket. Only Allan Border almost thirty years ago can be said to have faced a comparable obstacle. Border’s difficulties were, however, alleviated by a vision and unity of purpose among captain, coach and selectors which, sadly, does not seem readily apparent today. Combined with the inability of the Australian game to mine the rich seam of talent Lawrie Sawle and Bobby Simpson identified almost thirty years ago, Clarke’s challenge is a forbidding one indeed.

Leave a comment