Hobbsy: A Life in Cricket

Dave Wilson |

Hobbsy: A life in Cricket – the biography of former England, Essex and Glamorgan leg spinner Robin Hobbs – by Rob Kelly, was published in 2018 by Von Krumm Publishing, you can read our review here.

Robin Hobbs made his Test debut for England in the summer of 1967 playing three matches against India and one against Pakistan. After appearing in the opening Test of the 1967/68 tour of the West Indies he was dropped and didn’t feature in the Ashes series later that year. Out of the frame for England, Robin headed for South Africa at the end of 1968 where he and his fiancé Isabel were getting married. England had also been due in South Africa but the tour was cancelled as a result of the D’Oliveira Affair and in its place a tour of Ceylon and Pakistan was hastily arranged. It was intended that the tour party would be the same 16 players that had been selected for South Africa but following the withdrawals of Boycott and Barrington – both for health reasons – the selectors decided to reduce it to 15 players. With an extra spinner needed for the sub-continent, Robin was picked as the man to replace the two world class batsmen.

Excerpt from Chapter 10 of Hobbsy: A Life in Cricket

An imbalance of the tour party was the least of England’s problems; internal unrest in Pakistan meant that the country was as good as engaged in civil war. This was no time and place for a cricket tour but incredibly it was sanctioned and encouraged by a British Foreign Office keen to demonstrate support for the Pakistan President, Ayub Khan, who was considered a vital ally in the Cold War.

All of this was still to come as the tour party headed off to the peace and tranquillity of Ceylon for the first leg of the tour, arriving in Colombo on 22 January 1969. The four warm-up games were played in a festival spirit and in between the players relaxed playing golf and basking on the idyllic sands of the island’s beautiful beaches. “We played in Kandy and Colombo, there were thousands of people watching. I used to toss it up and got smacked all over the park, I got one for 70 in eight overs and one for 60, everyone was happy, people were running after the ball for the sixes and our captain, Colin Cowdrey, must have been thinking ‘He’s a bit expensive this bloke!’”

After the serenity of Ceylon the tour party flew on to Pakistan where they’d be playing three warm-up games before the start of the Test series. Robin played in the first of these games against the Control Board XI at Bahawalpur taking two for 71 in an attack which also included fellow spinners Pocock and Underwood.

Despite a good bowling performance Robin wasn’t selected for either of the final two warm ups. At one stage Robin had been left virtually alone in a hotel in Lahore while the rest of the team had headed off to Sahiwal, some 180 km away, to play a three-day match against the West Pakistan Governor’s XI. Without much by way of entertainment Robin turned to pitch and putt to keep himself amused.

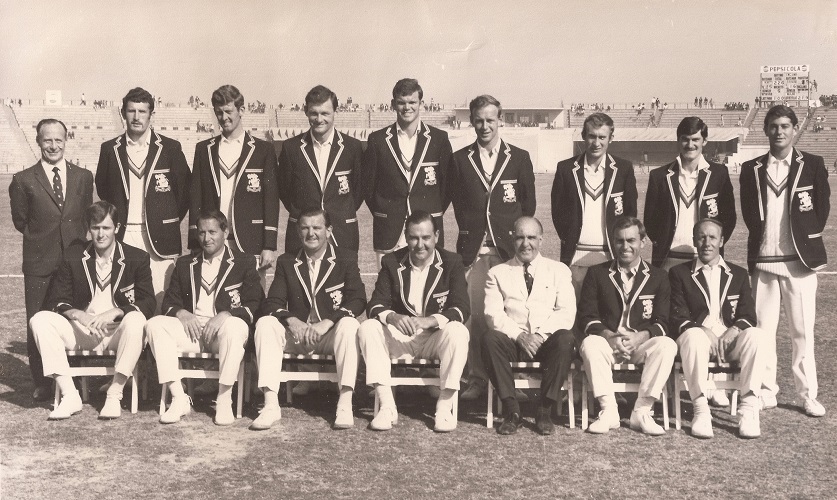

England team at the Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore, February 1969

Standing: Bernard Thomas (Physiotherapist), John Snow, Pat Pocock, Roger Prideaux, Bob Cottam, Derek Underwood, Keith Fletcher, Alan Knott, Robin Hobbs.

Sitting: David Brown, Basil D’Oliveira, Tom Graveney, Colin Cowdrey, Les Ames (Manager), John Edrich, John Murray.

The first Test at Lahore was drawn and Robin could only watch from the sidelines twiddling his thumbs, England preferring to go with the spin of Pocock and Underwood. There were a number of interruptions from protestors during the game, particularly on the first and last days, and an air of tension pervaded the ground as the England players were left wondering whether they might be forced to flee at any moment due to the inefficiency of the security forces’ efforts to keep control.

The second Test was at Dacca in East Pakistan and before departing a cable was received from the British High Commission there warning that the tour party should not come to that part of the country as their safety could not be guaranteed. When news broke that the team wouldn’t be heading to Dacca an angry mob promptly burned down the High Commission. Surprisingly, the following day a further cable arrived from the High Commission assuring that everything was now fine and that the tour should proceed as planned. It was Carry On up the Khyber stuff! “Poor old Les Ames was tearing his hair out,” Robin recalls, “he spent more time at the High Commission than he did at the cricket.”

Incredibly the Test passed off without serious interruption with the organisation of stewarding and security taken over by the student protestors themselves. On the field the match was drawn, Robin once again wasn’t selected and Pocock was dropped as England opted to go with three seamers and just one specialist spinner in Underwood. Pakistan on the other hand opted for four spinners and just one seamer.

The one bright light amongst all the turmoil was the arrival of Colin Milburn shortly before the start of the Dacca Test. Milburn – who’d just come to the end of a stint playing for Western Australia – was preparing to sail home to the UK when he was summoned to Pakistan where he was needed as cover due to injury concerns with Cowdrey. The journey from Perth to Dacca took 72 hours and Milburn emerged exhaustedly from the plane to be greeted by the whole England team, his arrival was a huge fillip. The mood was raised even higher by a few laughs at Milburn’s expense. Years later Robin stills chuckles away at the thought of that day.

When the plane landed we picked him up from the airport. We were staying in a decent hotel but there was a hotel we’d stayed at on the under-25 tour two years earlier which we called the Shag Bag, it was a dreadful hole. We picked him up from the airport, put him on the bus and we dropped him off at the Shag Bag, we told him there weren’t any rooms free at the Hilton and left him with his bags outside this bloody hotel.

After an hour the players returned to collect Milburn but the horror wasn’t over for him. By chance his arrival in Pakistan that day coincided with a religious festival which Robin remembers well with a mischievous smile.

It was the day of the year when the locals throughout Pakistan slaughtered an ox wherever it stood to feed the local village and so the whole place was covered in blood and carcases. Ollie’s reaction was priceless – “F***ing hell, what have I come to, there’s blood everywhere!”

The second Test was drawn and the tour party flew to trouble-torn Karachi for the series finale. By now Robin had given up hope of playing any further part in the tour and had got rid of all his kit, giving it away to grateful locals. Taking a look at the pitch in the days leading up to the Test Robin describes it as being “as flat as a table”. Not having played for a month he felt certain he had no chance of being selected and was relieved that he wouldn’t have to bowl to a Pakistan batting line-up well used to facing spin, and that in their own backyard. “Pakistan had a batting order that looked like a world eleven”, recalls Robin, “they had Hanif Mohammad, Majid Khan, Shafqat Rana, Asif Iqbal, Saeed Ahmed, Mushtaq Mohammad, they batted down to 11.”

To his bewilderment, Robin found himself selected anyway. The England selectors had originally opted to go with the same bowling attack as in Dacca but as the wicket dried they felt it would be a slow turner and so Bob Cottam was dropped and in came Robin, ridiculously short of match practice, something which he still recalls with a sense of astonishment.

Cowdrey said to me two days before the game “You’re going to play the next game Robin, we think you’re the chap to bowl them out.”

I said “You’re f***ing joking! I haven’t played or bowled a ball for five weeks.”

“We’ll sort that out this afternoon” he replied.

“Oh really, what are we going to do?” I said with more than a hint of sarcasm.

“We’re going to the nets, you and I, and you’re going to bowl 50 balls.”

And so, with less than two days to go before the deciding Test in the series, Cowdrey and Robin headed for the nets for a special practice. “Oh my God, oh God help us,” recalls Robin, “balls were going all over the place and there I was – Hobbs picked for the final Test in Karachi, trying to hide or run away.”

Colin Milburn was also brought into the side, replacing Roger Prideaux, and went on to score a magnificent 139 after England had won the toss and, much to Robin’s relief, opted to bat first. A number of pitch invasions and interruptions had occurred during the first two days and on the third the situation turned ugly following the death of a prominent anti-government leader. For Robin, short of match practice and contemplating the prospect of a mauling at the hands of the Pakistan batsmen, fate intervened and provided his salvation.

The anti-government protestors had been threatening all tour to disrupt the place and we’re playing in the national stadium in Karachi and I’m thinking ‘We’re 502 for 7, I’m going to have to bowl 25 overs here and I’m going to get smashed for 150 and this is the end of my f***ing life, I can see it happening.’ I couldn’t bowl a hoop down a hill and they had a batting order I couldn’t get any of them out, I would have got nought for 150. And then suddenly God looked down on me. The gates at the far end of the national ground opened and f*** me, about 500 people came bursting in. They set fire to all the hoardings, all the VIP lounges went up in smoke and there were two blokes out there with a f***ing shovel digging the pitch up and if I could have had another shovel I’d have been out there with them. I tell you what, was I happy!

One player who didn’t share Robin’s elation was Alan Knott who was on 96 not out and approaching his maiden Test century when the mob broke into the ground and brought a halt to the game. The England team took refuge in their dressing room and the Pakistan cricket authorities took the decision to abandon the tour. The players were as good as smuggled out of the ground back to their hotel where they hastily packed their belongings and headed for the airport where the tour manager, Les Ames, had managed to get everyone booked on the first flight out of Karachi. As the plane took off at midnight, Milburn rocked the cabin with a rendition of The Green, Green Grass of Home and Robin and the other England players broke into rapturous and relieved applause, flying home “as happy as Larry.”

It had been a strenuous five weeks on a tour which should never have been given the go-ahead. Other than Boycott and Barrington, none of the other players had pulled out before the start which, on reflection, may seem surprising but in that era international cricketers were not as financially secure. The original tour to South Africa would have lasted close to four months, the rearranged one lasted less than two. However, MCC – perhaps mindful of how fraught the tour would be – still opted to pay the players the same fee which made the ordeal well worth their while. Robin still chuckles at the whole experience: “I got two wickets which cost MCC £1000 – £500 a wicket.”

The whole tour had been a farce and the England team had been lucky to escape unscathed, the experience had been even more surreal for Robin with his strange recall for the third Test despite being completely short of bowling practice.

It was unbelievable, I was really sold down the river being picked for that last Test there and I only got out of it by luck, I didn’t bowl and came back unscarred by pure luck. I would have been slaughtered, I would have been smashed all round the park so that made up for the missed chances at Lord’s in 1967.

Playing in an abandoned Test did however bestow upon Robin a rare and dubious honour which he still sees the funny side of many years later. “I’ve been one of the few people to have played in a Test series who didn’t bat, didn’t bowl and didn’t even bloody well field.”

Hobbsy: A Life in Cricket costs £16 and is available direct from Von Krumm Publishing.

Copies are also available from the Essex Cricket Shop and Amazon.

Leave a comment