Cricketing Myths

Dave Wilson |

Cricketing Myths – Patrick Ferriday

Authour of ‘Before the Lights Went Out’, ‘Masterly Batting’ and ‘Supreme Bowling’, Patrick Ferriday provides some insight into cricketing myths, beginning with a famous pair of fast bowlers. You can read more about those and other pace pairs in his book ‘In Tandem’.

Myths are fun and usually survive because the light version is better than the more mundane reality. In that sense they have an uncomfortable relationship with fake news. They might make a good story but they are fiction posing as fact. Here is a personal cricketing list. I’m sure it’s not comprehensive but it’s a start.

Hall and Griffith

This pair of West Indian fast bowlers were where it all began. No longer the days of those little spinning pals backed up by a bit of medium pace. For the first time the Caribbean had an attack to terrorise the best batsmen in the world and, with the odd hiatus, their team would continue to do the same for the next 50 years. Except it simply wasn’t like that.

Wes Hall came to prominence in 1958/59 by taking 46 wickets in his first eight Tests – all in Asia. For the next five years he didn’t so much ply his trade as roar it from the rooftops from Brisbane to Bacup to Bridgetown. He hurled himself into everything, made himself the most thrilling fast bowler ever seen and wore himself out within five years. When Charlie Griffith arrived to share the load in 1963, Hall was just as exciting to watch but much easier to play (even despite Colin Cowdrey’s broken arm). His average before was 21.87 for 116 wickets, thereafter his 76 wickets cost 33.27. The colossus of the tied series was, after all, merely mortal. Griffith’s 32 wickets in England in 1963 was a series-winning performance but dogged by allegations of ‘chucking’ his form and fitness dived.

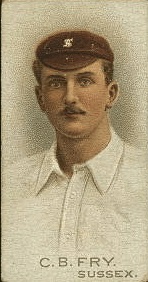

King of Albania

Apparently Ashley Giles wasn’t the first England cricketer to be offered the monarchy of a European nation – as in most things, CB Fry got there first. The all-round glories and tales of this modern-day Hercules abounded and when the Albanian government were casting around for a new king in 1920 then Fry was one of the names to come into the reckoning. He was not the first choice but the Albanian envoy was looking for an English country gentleman with an annual income of £10,000. Fry didn’t exactly fit either category and even Fry himself admitted that no direct offer was made. Certainly there was no possibility of accepting without Fry’s great friend and one-time county colleague Ranjitsinji bankrolling the entire enterprise. When he declined then Fry was out of the running without ever really having been in it.

The Heavy Ball

It pitches back of length, rises and strikes the bat just below the splice. Even a modern bat can jar the hands when thudded by 5.5 ounces of leather impacting at 80-odd mph. That’s not the issue. Any quick bowler can deliver this heavy ball with the requisite speed and placement. But in there somewhere is the demand that the heavy ball is delivered by the heavy bowler. Tim Bresnan and Jacques Kallis were two – neither particularly quick but both somehow heavier than, say, Glenn McGrath (if he bowled short) or Dale Steyn.

Joel Garner, Jeff Thomson and Curtly Ambrose are three quicks lauded and feared in equal measure for their ability to get a ball to rise abruptly from only just short of a length. Larwood or Lindwall needed to bowl a bit shorter to get the same lift. None of these were heavy-ball bowlers or at least they are not described as such. Instead we look for a ‘big strapping lad’ or a paceman who ‘likes his dinner’. Heavy does as heavy is.

Bobby Peel’s Indiscretions

The legendary soak Peel had decided to get absolutely smashed, well maybe not ‘decided’ it just happened. Why not? England had all but lost the first Test, with Australia 113-2 chasing 177 on a shirtfront. But then it poured and a steaming sticky awaited the players the following morning. England’s own steaming sticky was put under a cold shower and bowled his side to a 10-wicket win.

Peel had a simple relationship with the bottle, he loved it more than anything and it was precisely this predilection that Lord Hawke was trying to remove from Yorkshire cricket. It was never going to end well. Legend tells of a hammered Peel taking the field at Sheffield in 1897 and variously bowling a ball that hit the sightscreen on the full before urinating either on the selfsame screen or even the pitch. He never played for Yorkshire again. Unashamed cribbing from Stephen Chalke’s Summer’s Crown shows that Peel was indeed drunk, bowled seven poor overs and slipped over on a number of occasions, due to missing spikes on his left shoe, before leaving the field with an injured knee. Peel moved to the leagues, lived until a ripe old age and was replaced at Yorkshire by Wilfred Rhodes.

Gettin’ ’em in Singles

It’s a famous situation. England, rescued by Gilbert Jessop’s whirlwind hitting, are now in with a chance of reaching their target of 263 to win. George Hirst has been batting steadily and his new partner, at 11, is fellow Yorkshireman Wilfred Rhodes. Fifteen more are needed. Did George say to Wilfred “We’ll get ‘em in singles”? Did he ’ell as like. Why would he? He might well have said “take it steady” or some such but two pragmatic players would hardly turn down a leg-stump full toss. And neither did they – Rhodes hit a boundary and the game was won. Fortunately we have an eye witness – one of David Frith’s ‘Encounters’ was with Rhodes himself and the question was put. ‘Hogwash’ confirms Frith, “It were some press man’s invention” confirms Rhodes. In a recorded interview, Hirst confirmed that they decided to play their normal game – which included boundaries. That should really be the end of that – but it won’t be.

Pace Before 1914

The tales of pre-1914 pace bowlers are legion. Ernie Jones parting the doctor’s beard, Albert Kortright sending bails to the boundary or Tibby Cotter smashing stump after stump. But by and large they are tales and the overwhelming evidence points to genuine fast bowling being largely an undiscovered art until Gregory, McDonald and Larwood in the inter-war years.

With no speed guns or reliable film footage how do we judge? Contemporary reports can be misleading but contemporary comparisons can also be revealing. South African JJ Kotze is usually bracketed with the quicks of the Edwardian age – but his ’keeper Ernest Halliwell was in the habit of standing up to the stumps. Look at pictures of Tom Richardson or Kortright in action and the wicketkeepers are barely five yards behind the stumps although the slips are plenty further back. George Hirst and Monty Noble both had their ‘keepers up. Tiger Smith often stood up to opening ‘quick’ Frank Foster

Go back a decade and Charlie Turner is described as ‘medium paced’ or even ‘medium fast’; he was in fact a spinner and was accurately measured at 55mph. Maybe Jones and Cotter were quick. Maybe. Jones took 32 wickets in four Tests at 17 each which smacks of something special. Unfortunately this was sandwiched in the middle of 15 other Tests where he managed just 32 more wickets. Cotter lasted longer but nothing points to him being outrageously fast compared to English contemporaries such as Fielder or Brearley. The very fastest bowlers were averaging less than 80mph.

Atherton’s Heroics

The biggest criticism I got from English readers when Masterly Batting listed the top 100 centuries in Test cricket was the omission of Mike Atherton’s famous rearguard epic at Johannesburg. Five sessions to bat, play for a draw, heroic resistance – the only thing missing was a jammed Gatling gun.

Captain courageous saved the day and there’s no argument with the 643 minutes and 492 balls, it was indeed some performance. But one of the great innings ever? Jack Russell stayed, against an admittedly tiring attack, undefeated for 235 balls. The pitch was flat and the bowling (bar Allan Donald) uninspiring. A wayward Pollock in his second Test, Meyrick Pringle (five Test wickets at 54) with the new ball supported by Brian McMillan topped off with 52 overs of spin from Clive Eksteen (eight Test wickets at 61.75 each). This is not to decry Atherton’s patience, tenacity and courage but surely the great innings require more difficult conditions and certainly a better bowling attack? Perhaps the awe and reverence surrounding this innings says plenty about those who loved it so much. Gallantry under fire saving the day.

Buck Llewellyn

When the South African opening batsmen came out onto the Kingsmead turf on November 13 1992 it was already a much-heralded day to remember. After the walk to freedom and 22 years in the wilderness, Test cricket was finally returning. At 206-6 the deal was well and truly sealed as Omar Henry came out to replace his captain, and centurion, Kepler Wessels. The world’s press trumpeted the first non-white to represent South Africa at cricket; except he wasn’t.

Fully 96 years earlier, 19-year-old Charlie Llewellyn had represented his country against England at Johannesburg. It was to be the first of 15 Tests spanning 16 years – during a break of eight years midway through this career Llewellyn played with great success for Hampshire and in 1902 was even included in the squad for England to play Australia. His subsequent career in the northern leagues lasted until 1935.

It was a fine career for a fine allrounder but sadly his uniqueness lies in his skin colour. Llewellyn’s father was, unsurprisingly, Welsh and his mother a Malay immigrant from St Helena. He owed his selection into the national team to two main factors – great cricketing skill and a light skin tone. This was not a South Africa of enshrined Afrikaaner apartheid but English-sponsored racism led by Cecil Rhodes and his cohorts. They had banned quick bowler Krom Hendricks but turned a blind eye to Llewellyn. If this sounds absurd (or obscene) it’s worth remembering that 60 years later Grahame Thomas of Australia was only allowed to tour South Africa once photographic evidence had been produced to show that his appearance wasn’t really ‘negroid’. Sadly, Llewellyn’s daughter later felt the need to dispute the facts her of grandmother’s birth, but facts they are.

Wrong-foot bowling

Mike Procter’s bowling action was odd but it wasn’t that odd. The idea that he actually pivoted on his right foot while bowling high-pace right arm is just plain absurd and a physical impossibility. What he did do was bowl chest on and release the ball incredibly late in his action, so late that his right leg was as good as past his left leg when the ball left his hand. But that left foot was still firmly planted. Just have a look on YouTube.

Leave a comment