No Justice for the Judge

Martin Chandler |

English cricket has had a few false dawns over the years none more so than in 1988. In 1984 and 1985/86 the national team had lost consecutive series to the West Indies 5-0 and, the occasional flash of individual skill apart, had looked a thoroughly second rate team. There was however genuine belief in 1988 that things might be about to change. It was true that in Malcom Marshall the men from the Caribbean still had a great fast bowler at the peak of his powers, but two more, Joel Garner and Michael Holding, were now retired. In those days the ODI series preceded the Tests and a 3-0 clean sweep for England convinced many that the balance of power had shifted, and that we would have the first competitve series between the sides for more than a decade.

The first Test was played at Trent Bridge and Marshall, with Curtley Ambrose mopping up the tail, dismissed England for 245 before all the West Indian batsmen, Marshall and Ambrose included, chipped in to produce a first innings lead of 202. The optimists were however buoyed for a little longer as Graham Gooch and David Gower led England’s second innings to 301-3 and a comfortable draw. A few still believed that the tide was turning.

After the match a story broke in the tabloids about England skipper Mike Gatting and he was summarily dismissed for “inviting female company to his hotel room for a drink in the late evening”. Having just received a bonus for his performance in a series when he became involved in an unseemly row with an umpire on the field of play it did and does seem a ridiculous decision. Gatting’s record as skipper, the Ashes success of 1986/87 apart, was dismal but his sacking cannot have helped the English cause, as under the temporary leadership of John Emburey the side then rediscovered all its old fragility to lose the second Test comfortably. The third was a mauling. Marshall was at his best as he led a new pace quartet comprising himself, Ambrose, Courtney Walsh and Winston Benjamin.

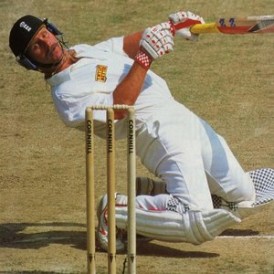

England lost the fourth and fifth Tests too, and it was clear that little had changed, but there was a debut for Hampshire’s Robin Smith, and he made an auspicious start. It wasn’t weight of runs that was the cause of the pleasure that Smith gave, 106 runs in four completed innings was no more than a modest return, but it was the way he scored them that was the cause for optimism. Smith always looked fidgety and nervous at the crease, constantly stretching and looking around him, but in a very positive way that inspired confidence. His technique was sound and he kept his eyes riveted on the ball every inch of the way. If the delivery was short and aimed at him he would rock back, as in the image that accompanies this feature, and let it fly harmlessly past his eyebrows. If it was on a length he was right behind it to treat it on its merits, but the real delight was the short one wide of off stump which would usually be met with what was surely as powerful a square cut as the game has seen.

On debut Smith found himself coming in with England, at 80-4, in difficulty. He gave us all hope though as he and Allan Lamb took the attack to the bowlers and started to get the England score moving. It was exhilarating to watch one particular delivery that Smith faced from his county colleague Marshall, where he went down on one knee to drive to the cover boundary. On the second morning the stand had progressed to 103 when disaster struck as Lamb pulled up lame and was forced to retire hurt. A combination of that interruption to his concentration, followed immediately afterwards by a brutal lifting delivery from Ambrose, saw Smith go for 38 and 18 runs later England were all out and on their way to a 10 wicket defeat. Smith managed one trademark square cut from Marshall in his second innings before being trapped lbw.

England lost the fifth Test too, comfortably in the end by 8 wickets, but they did take a first innings lead in a low scoring match thanks mainly to Smith, who top scored with 57. He hooked his very first delivery from Benjamin for four and left no one at the Oval in any doubt but that England had now found a young batsman good enough to grace the international stage.

England had no tour in 1988/89 so the next Tests that Smith appeared in were in that hugely disappointing, for England anyway, Ashes series in 1989. The scoreline was 4-0 to Australia, who also had by far the better of the two rain affected draws, and only Smith, who averaged more than 60, brought any crumb of comfort to England supporters. His first Test century came in the fourth Test when he scored 143 out of England’s first innings of 260. Wisden commented It was a fine innings by any standards; amidst the fragility of so many senior players it was outstanding.

As an established player there were many memorable knocks from Smith but a few will always stand out for me. The first was at Sabina Park, Kingston in February 1990, the famous game when, for the first time in 16 years, England defeated the West Indies. In terms of their respective roles in that victory, Lamb with the bat, and Gus Fraser, Devon Malcolm and Gladstone Small with the ball are properly remembered in front of Smith, but without his defiant and painstaking 57 which, with Alan Lamb’s contribution, added 172 for the fourth wicket, it would almost certainly have been business as usual for the home side.

In 1991 Smith was at the peak of his powers as a batsman, averaging 83.20 against the West Indies. He top scored with 54 in the first innings of the Test at Headingley that was eventually dominated by Graham Gooch’s momentous second innings 154*, but it is his contribution to the drawn second Test that sticks in my memory, and in Smith’s own view was his finest Test innings. West Indies teams of the early 1990s were not quite what they had been a decade before but they still took grave exception to being defeated. Batting first the tourists posted 419 and, with England reeling at 84-5, a crushing defeat looked on the cards. Smith had other ideas though and he added 96 with Jack Russell, 89 with Derek Pringle, 50 with Phil De Freitas and then 39 with Steve Watkin before he ran out of partners, unbeaten on 148*, and with the game saved. Wisden described it as seven hours of graphic concentration. David Frith wrote of his partnership with Russell Robin Smith had played one thrilling stroke after another in an innings which was to grow in size and technical quality to match Gooch’s in the Headingley Test. The Hampshire man’s strength injected hooks and square cuts with a power which bordered on the supernatural, and seldom if ever can Lord’s have witnessed such speed of ball through square cover.

My third abiding memory of Smith actually comes from an ODI. I enjoy ODIs as much as anyone but over the entire forty year duration of their existence they have failed to fire my imagination sufficiently to enable me to easily recall individual matches, so much so that only two have ever stuck in my mind. One was a quite awesome 189* from the masterblaster himself, Vivian Richards, at Old Trafford in 1984, and the other was Smith’s 167* for England against Australia at Edgbaston in 1993. No other England batsman scored more than 36, and Smith got his runs in just 163 deliveries with 17 fours and 3 sixes. England lost the game, quite comfortably in the end, but that detail is irrelevant. What sticks in the mind are the last seven overs of England’s innings in which Smith added 70 on his own. The display of grimaces, scowls, snarls and glares that the withering assault brought forth from Merv Hughes was almost as memorable as the innings itself.

The last memory of Robin Smith that my mind’s eye can show me without having to resort to archive footage does not even include a half century, but as Mike Atherton commented at the time his innings of 46 and 41 at Edgbaston in 1995 against, inevitably, West Indies, were worthy of a pair of centuries. The preparation of the pitch was a disaster and the smile on the face of that well known curmudgeon Ambrose, following the very first delivery of the match, was testament to that. The big man’s loosener pitched about half way down and took off to such an extent that it cleared wicketkeeper Junior Murray by a good four feet to go for four wides. Smith was eighth out for 46 in an England first innings of 147. West Indies lead of 153 was plenty as England were routed second time round for just 89. Of Smith’s 41 Jack Bannister said Smith showed what could be achieved by unflinching courage, immense concentration and the ability to play straight. As he watched the bombardment for Test Match Special Fred Trueman, for once knowing exactly what was “going off out there”, saidOne thing I know: Robin Smith will not be sleeping on his left hand side for a while.

After his heroics at Edgabston Smith got to 44 in England’s first innings of the fourth Test at Old Trafford but in the second innings he failed to get out of the path of an Ian Bishop thunderbolt and suffered a fracture cheekbone. He played no further part in that match or the last two Tests. Smith was not yet 32, and was to play the First Class game for another eight years but, remarkably, by the time the next English season began, in April 1996, he had played for England for the last time.

Fit again for the South African series that winter it is fair to say that Smith did not have a particularly happy time with the bat. It was a series England lost 1-0 and, had it not been for Michael Atherton’s remarkable 643 minute 185* at Johannesburg that would have been 2-0. Smith did his bit at Jo’burg, keeping his captain company for a couple of hours and scoring 44, but there were just two half centuries for him in the series and a disappointing average of 36.28. It is worth noting however that only Atherton and Graeme Hick bettered that average so there was no apparent need to panic. From South Africa it was off to the sub-continent and a disappointing World Cup campaign for England who lost a quarter-final to the eventual winners, Sri Lanka. Smith only made the side twice, pressed into an opening berth that he was not used to, but scores of 75 and 25 represented a perfectly respectable return in terms of runs scored.

So what went wrong? The essential problem, although surely not all of it, was simply down to the way in which Smith was managed. Despite the way he played the game he has always been the first to admit that he suffered from fragile confidence and a need to be encouraged to believe in himself. At the start of his Test career the man in charge of England was Mickey Stewart, of whom Smith says, He was outstanding. Throughout my early career Mickey was a wonderful manager. He encouraged me, he backed me…

By the time England toured India in 1992/93 Keith Fletcher was in charge of the team and Ray Illingworth was Chairman of Selectors. These were dark days for England and during Fletcher’s tenure, which ended after he was sacked following the unsuccessful Ashes campaign of 1994/95, they won only five Tests as against 15 defeats. From the West Indies series in 1995 until the conclusion of the ill-starred 1996 World Cup Illingworth assumed Fletcher’s role as well as his own to become, briefly and unsuccessfully, an overall supremo. Smith does not mince words regarding Fletcher and Illingworth ; ..in my opinion those two were the most appalling man managers, the most appalling coaches and the most appalling people that I’ve ever met

Smith’s antipathy towards Fletcher was clearly mutual and that must, given Fletcher’s role as Team Manager, reflect more to his detriment than Smith’s. Indeed in Fletcher’s 2004 autobiography he takes every opportunity to snipe at Smith and has barely a good word to say for him. Bearing in mind that when Fletcher took over the Team Manager’s position Smith was still only 29 his description of him as being past his prime seems bizarre.

In the book he did come close to saying something positive twice. First is a passage that begins When I was coach, Robin Smith was one of the few batsmen likely to make runs consistently …. although in fact he just used that comment as a stick with which to beat Smith immediately going on to add … but he was not always focused on his game. He had business interests and was also a party-goer. In the very next sentence he then had the temerity to suggest that Smith’s commitment to the England cause was less than absolute; Even if players had lived in England from a young age, some did not necessarily identify with it. National identity was being watered down. Some books are clumsily put together, particularly after the final proofs are checked, and the seemingly nonsensical sentence that follows No one could ever say that he did not give his all , but I wonder to what extent we would have been worse off without these individuals had surely been tinkered with by a somewhat dyslexic libel reader.

The second example was a comment about the common misconception that Smith was a poor player of spin, and relates directly to the Australian Tim May, sometime off-spinning partner of Shane Warne and while a decent bowler, not in the same league as his illustrious colleague.Our batsmen should have tried to hit him off his length. Robin Smith for one, gave him too much credit. Smith was a far better player of spin than most of the others but he read too many newspapers and listened to what every media pundit was saying. Smith should have been capable of bullying spinners in the same way that Gooch did. It does seem odd that the distracted businessman/party-goer would have had enough time in which to read the sports pages and listen to what every cricketing journalist was saying, but there you have it from the Team Manager.

Fletcher has another go at Smith’s dedication and, by implication, his courage, in some comments about the 1993/94 Caribbean tour which, again, I suspect may have had a positive gloss added by the libel reader; Robin Smith was affected by the uneven surfaces that we came across throughout the Caribbean – that and his love of the good life. He, too, was a likeable individual and I admired his thorough loyalty to Hampshire …. but he could have done with a measure of (Alec) Stewart’s dedication on that tour. Twice he overslept when he was supposed to be at the ground …. Fletcher does not say what ground he should have been at and for what purpose, but it seems likely that had it been for a match he would have said so in terms and Smith would surely have been severely censured. Why Smith should be singled out for mention on the subject of pitches on which all the England batsmen struggled is beyond me, and I am left with the feeling that the second part of Fletcher’s criticism amounts to no more than a case of a senior player being late for nets occasionally, hardly unusual in that era.

Later in the book, while discussing the desirability of batting practice and the benefit or otherwise that some great players derived from it, Fletcher accepts that the likes of David Gower, Garry Sobers and Ian Botham didn’t ever seem to be adversely affected by giving nets a swerve in favour of a bit of sleep after some socialising. At the end of the relevant paragraph, for no apparent reason, the following sentence pops up; The difference between Botham and Robin Smith when he favoured similarly late nights a decade later was that Smith let himself down in the middle. In reality that is an accusation that Smith was unprofessional, and really ought to be backed up by some specific facts, but I looked in vain for any evidence to back the allegation up.

As for Illingworth he published a controversial book during 1996, One Man Committee. although the furore it caused surrounded comments he made about Devon Malcolm. Inevitably Smith’s name crops up regularly but there is nothing to indicate whether or not Illingworth concurred in the views later expressed by Fletcher. Perhaps Illingworth’s ghost, Jack Bannister, whose admiration for Smith is clear from where I have quoted him above, had something to do with that – or perhaps Illingworth simply had no opinion about Smith.

Whatever the failings of Fletcher and Illingworth might have been the reality is that Fletcher was gone in 1995 and Illingworth’s last act as Chairman of Selectors was to help pick the parties that went to Zimbabwe and New Zealand in 1996/97. How close Smith ever got to selection again is unclear. The man appointed England coach in 1996, David Lloyd, did not even mention Smith in his 2000 autobiogaphy so certainly he would not seem to have been to far up his list of possibles. Smith himself has said that he was assured on various occasions by members of the selection panel that he was still in their thoughts and that he needed runs for Hampshire. He got those runs from time to time, but generally as far as the Championship was concerned he was more of a Gower than a Hick and his county form for the remainder of his career was steady rather than spectacular.

Press and public alike would, as the 1990s wore on, often bemoan Smith’s absence from the England side. In 1997 during the Australian backlash after England had had the temerity to win the first Test of that summer’s Ashes series his great qualities were sorely missed. On their subsequent visit to the Caribbean in early 1998 England lost the series 3-1 and three of their frontline batsmen averaged less than 20. I would not suggest that the Judge’s presence would necessarily have changed the outcome of the series. But I am sure that the West Indians were delighted that he was not included in the touring party. In my opinion, and that of many others, Smith was jettisoned by England far too soon. He was still one of the top batsmen in the country when he lost his place and, the selectors and management in those days having such poor inter-personal skills, he was treated appallingly. But he can hold his head up high – I and everyone else who saw them will always remember his great innings. In the end there was little justice for Robin Smith, but he left an unforgettable legacy.

Loved his work.

Comment by robelinda | 12:00am GMT 25 November 2011

One legacy from Robin Smith is that most modern batsmen followed him into the gym and now have forearms bigger than my legs…

Comment by Flametree | 12:00am GMT 25 November 2011

Good read that, was a true fighter. I remember after they beat Aust in a ODI the Poms taking pics of him with a bulldog. I think only him Lamb and Gatting could have pulled that off.

The rest of the team would have been laughable with anything outher than a poodle at their side

Comment by archie mac | 12:00am GMT 27 November 2011

Really enjoyed reading that, one of my very favourite players when I was younger. When I was about 8 or 9 I used to have a picture of him (playing the square cut obviously) on my bat after I decided to go all Brian Lara and take the stickers off, don’t think I have ever successfully played that shot in my life but I certainly tried enough times.

My only real memory of him as an England player was when he fractured his cheekbone, remember my dad saying at the time he feared it would be the last time he would play for England, had totally forgotten he was on that tour of SA.

Comment by Pothas | 12:00am GMT 27 November 2011