World Sports Magazine Review – 1948

Dave Wilson |

Following the earlier pieces on the sports magazine World Sports, which can be found here and here, part three features extracts from magazines published in late 1948 which naturally included the visit of Bradman’s Invincibles to British shores for what would be the great man’s swansong.

In the September 1948 issue, the first item of interest to cricket fans is a “Cinestrip” which shows “magic eye” photos of Lindsey Hassett, illustrating to aspiring batsmen how to execute the leg glance. But the main cricket interest is in that issue’s piece by famed cricket scribe Neville Cardus on “Cricket’s Peter Pan”, the eternally youthful Denis Compton, which opens ‘I have always fancied that a cricketer – if he is in possession of an instinctive technique – somehow expresses his personality and the period in which he was born.’ Contrasting the more mature technique of Bradman with the boyish exuberance of Compton, he notes the latter “runs between the wickets with an invisible school satchel flapping behind his back, elbows up, in a hurry and a little late…No wonder he is the most popular cricketer of all in the estimation of boys and girls everywhere.’ Compare that with the young folk of Australia, whom Cardus has never heard ‘crowing like cocks at the appearance through the pavilion gate of Bradman. The applause has always been…rather elderly.’ Keith Miller, meanwhile, represents young Australia’s ‘conception of glamour in action on the cricket field.’ The difference, Cardus goes on, comes from the fact that ‘hundreds of years of living, in all the ways of experience, are required to evolve and perfect a Compton.’ This somewhat romantic view might explain why Australia’s alleged apparent seriousness has always resulted in more success than England has enjoyed.

Cardus does however discuss Englishman Douglas Jardine in terms equivalent to his more forthright description of Australian cricketers, even going so far as to use the phrase ‘un-English’. He then goes on to discuss the relative ‘Englishness’ of the other Test nations, New Zealand and South Africa being more so than those who wear the baggy green, with the point being that Compton is quintessentially English specifically in regard to his cricketing character. Such unconcealed nationalism, evidenced by the use of terms like ‘not racially English lands’ when referring to such far-flung parts of the old empire as India, is a little eye-opening and reminds the present day reader that these pieces are now 70 years old – different times indeed.

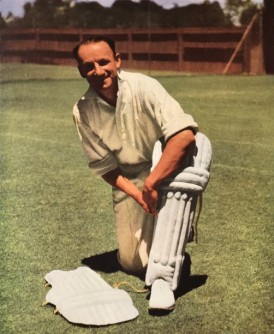

In the following issue of October 1948, Cardus penned a farewell to Bradman entitled ‘The Wizard of the Willow’. After his first innings in Britain, 236 against Worcestershire in 1930, the great Wilfred Rhodes noted he was ‘the best back-footed player’ he had ever seen; later that summer a newspaper headline trumpeted BRADMAN FAILS, after he had been dismissed at Glamorgan for a “paltry” 58. According to Cardus, Bradman’s great contribution had not been in the advancement of technique but with ‘an incredible concentration of a new economy.’ Although being past his peak, Bradman in 1948 scored more than 500 Test runs at 72.57 despite two ducks, the highlight being an innings of 173* at Headingley, taking his Test average at that ground to an incredible 232.50. Even so, Cardus considers WG Grace to be in ‘another dimension’ while pointing out the poor state of the wickets which the Grand Old Man played on. Strangely, the statistics quoted for Bradman’s Test career are incorrect – 80 innings, 10 not out, 6988 runs at 99.82; I’m not aware that eight runs were subsequently credited to him.

Cardus’ praise of Bradman is admittedly a little grudging with a sort of ‘yes, but…’ qualification to it all, such as ‘cold-blooded yet thrilling’ or ‘a ruthless little man, but with it all, a pretty humour’ and finally a questioning ‘Greatest of all?’, which Cardus answers with Grace’s famous pronouncement of ‘Give me Arthur [Shrewsbury].’ As Bradman retired 100 years after the birth of WG Grace, Cardus noted that ‘the great wheel has come full circle.’

Finally in 1948, the December edition sees Cardus waxing lyrical in ‘Cricket by the hearth’. This was a more fanciful piece imagining a session in the psychiatrist’s chair with Cardus responding to word-association. ‘Batsmanship’ brings to his mind CB Fry, of whom he writes ‘His influence on batsmanship has been stronger than anybody’s, including Hobbs and Bradman, since WG and Arthur Shewsbury.’ This piece allows Cardus to give full rein to his story-telling side, featuring Emmett Robinson subbing from the members seats at Leeds, and AC Maclaren captaining Stanley Jackson, “Plum” Warner and Gilbert Jessop at Lord’s.

Also in this issue, Rand Daily Mail journalist Paul Irwin discussed the probables for South Africa’s team to face the MCC in the latter’s upcoming tour, considering that Dudley Nourse may be an overly cautious captain, and that Eric Rowan would return to the side despite being now 39. As it turned out, Rowan averaged over 50 while a sporting declaration by Nourse in the final Test, rather than taking the safe option of forcing a draw but losing the series, brought much excitement with the chance of a possible victory to square the series.

Finally, the Scrapbook of Sport regales readers with the story of how the Duke of Queensberry won a heavy wager that he could not, in those days of horse transport, send a letter 50 miles in a short time. He won the bet by enclosing the letter inside a cricket ball and engaging a team to stand in a circle and pass it rapidly round until the distance had been covered. Presumably not a Murali among them.

Leave a comment