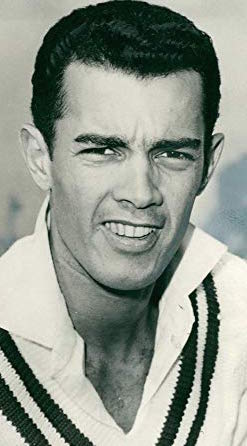

Charlie Davis – Trinidad and West Indies

Martin Chandler |

After how many Test matches can an average be treated as a true measure of a batsman’s worth? Most seem agreed that in order to be considered a good Test batsman a man has to average at least forty, and that the mark of a great is a figure north of fifty. Are fifteen matches enough? If so then the fact that Trinidadian Charlie Davis is all but forgotten is, to say the least, unfair. Between 1968 and 1973 Davis played three Tests against Australia, three against England, four against India and five against New Zealand. He ended up with 1,301 runs at an average of 54.20. Of those who have batted more than twenty times in Tests, and excluding those currently plying their trade, only seventeen men in the history of the game have finished with a higher mark.

Davis was born in Trinidad on New Year’s Day in 1944. There was no family history of cricketing prowess, but Davis’ mother played hockey for Trinidad, and he was not the only one of her five children to play cricket for Trinidad and West Indies. Elder brother Bryan was an opening batsman who played four times in the Caribbean against Australia in 1964/65 recording three half centuries, but not passing 68. He was talked about from time to time after that but, perhaps surprisingly in view of the fact that it was not until the early 1970s that West Indies had a settled opening pair, was never selected again.

As a 17 year old Davis recorded his first century in just his second First Class appearance, for North Trinidad against South Trinidad. Six months later he got his second against British Guiana, a particularly impressive performance bearing in mind he came in at 15-4, and after his side slipped to 81-7 he shepherded the tail up to 257. The innings neither avoided the follow on nor, ultimately, defeat, but it showed Davis had the temperament to deal with pressure situations.

With India touring the Caribbean in 1961/62 and after that spectacular start Davis might have been capped soon after his eighteenth birthday. He was named in a ‘squad’ of 23 for the Test series although in the event no place opened up for him. At this point Davis might have been lost to West Indies cricket completely as his early impact had been noted more than 4,000 miles away in Gloucestershire. The county offered terms to both Davis brothers, but professional cricket in England, which would have involved giving up any hope of a Test cap and a long wait for a residential qualification appealed to neither. At the other end of his career, once the counties were able to specially register overseas players, Bryan did spend a couple of successful summers with Glamorgan, but it was never a way of life that his younger brother considered.

By the time England, under Colin Cowdrey, arrived in the Caribbean in the New Year of 1968 Davis was on the verge of Test selection. He played against the tourists in their first big game of the tour, for a Board President’s XI, and scored an unbeaten 158. In his account of the tour Brian Close wrote that he played with such confidence and freedom that his century looked inevitable. Davis lined up against Cowdrey’s men again in their next match, on his home ground in Port of Spain. He scored 68 and 62.

The selectors must have thought long and hard about including Davis in the side for the first Test, also to be played in Trinidad, but in the end could not find a place for him. Davis and his fellow Trinidadians must have been disappointed, but the only place he might have taken was that of Clive Lloyd, who had had an excellent first series against India the year before. In the circumstances the decision to omit Davis was a reasonable one and despite the series eventually going England’s way after that remarkably generous declaration by Garry Sobers in the fourth Test West Indies’ problem that series was their bowling, rather than their batting, and no middle order vacancies appeared.

In 1968/69 West Indies, for the first time since the historic 1960/61 series, visited Australia. His deeds against MCC remembered Davis was in the party, although he was still unable to force his way into the side for the first Test, won by West Indies thanks in large part to a fine century by Lloyd. The centurion went on to damage a forearm in the field however, and was consequently unfit for the second Test. Davis, described as off colour, also had fitness problems but did make his debut, albeit not in place of Lloyd but, having just taken seven wickets in a state match with his occasional right arm medium pace, instead of all-rounder David Holford, who despite taking a couple of wickets had failed twice with the bat in the first Test.

West Indies batted poorly at the MCG and were 170-6 when, batting at eight, Davis joined Roy Fredericks. Seven runs later Fredericks was gone as well, to be immediately followed by Jackie Hendriks, and although Davis batted well he was bowled for 18 by Graham McKenzie with the new ball, looking for opportunities to farm the strike. The use of a nightwatchman in the second innings brought Davis in at nine, and it was a repeat performance. He looked comfortable enough but went for 10. Australia won by an innings. In the Australian innings Davis did have the pleasure of taking the first of his two Test wickets, Bill Lawry, but ‘The Phantom’ was 205 at the time.

For the third Test of the series Lloyd was back and, his replacement Fredericks having been one of the few to emerge from the MCG with any credit, it was Davis who made way. With just a single half century and an average of 16 for the tour as a whole Davis did not get another chance as Australia won two and drew one of the remaining three Tests.

For some reason Davis did however find that niche in Australia with the ball. All told he took 21 wickets at 30.66 to finish top of the tour averages with his right arm medium pace. It was a false dawn, but a useful one for Davis as it persuaded the selectors to take him to England for their visit here in the first half of the 1969 summer, as an all-rounder.

Perhaps surprisingly England, a happy hunting ground for gentle medium pacers, saw Davis reverse his Australian experience. His seven wickets on the tour cost almost seventy runs each, and in the averages he was last of thirteen. Fortunately for him however he made some progress with the bat in a three Test series that the visitors lost 2-0. The paying public, who had watched Sobers lead his 1966 side to a stunning victory saw just five of that party returning, a less than fully fit Sobers and Caribbean cricket in disappointing decline.

The first Test, at Old Trafford, was won by England by ten wickets, helped in part by some slack fielding with Davis bearing his share of the blame. With the bat he top scored with 34 in the first innings and then added 24 in the second. The Sage of Longparish, John Woodcock, described him in The Cricketer as batting splendidly, but not for long enough.

The Lord’s Test was by far the best of the three, the game ending with England 37 runs short of victory with three wickets to fall. In the West Indies first innings Davis had put on exactly with 50 with his captain when, in a misunderstanding that certainly appeared to be Davis’ fault, Sobers found himself in no man’s land to give Geoffrey Boycott an easy run out. Davis decided the only way to avoid the wrath of his teammates was to stay in the middle for as long as possible, and he did so for over six hours. In that time he scored 103 and was in defensive mode throughout. Close would certainly not have applied the same description to this incarnation of Davis as he had to that of the previous year.

After his intense feat of concentration in the first innings Davis was out for a duck, for the only time in his Test career, in the second. The third Test was, on a personal level, much the same as the first for Davis as he scored 18 and 29, but the English margin of victory was rather different, just thirty runs, so another half hour from Davis after one or other of those starts and the series might easily have been shared.

By the time West Indies were next in Test action, against India at home in early 1971, Davis was out of favour once again and missed the first Test of what became a historic series the Indians, courtesy of four draws and a victory in the second Test, winning a major series overseas for the first time. The first Test was drawn, and there was much controversy over the claims for batting places of Jamaicans Lawrence Rowe and Maurice Foster being ignored. Contemporary reports express no such concerns over Davis’ omission.

The Indian spin attack having shocked the West Indians by making them follow on in the first Test the selectors thought long and hard about the batting for the second and Davis, who had made exactly 100 in Trinidad’s game against the tourists, and in doing so made Venkat look rather less troublesome than he had appeared the first Test, was eventually given the nod to replace the injured ‘Joey’ Carew, his fellow countryman.

Sobers won the toss and chose to bat. By the end of the first day Bishan Bedi and Erapalli Prasanna, with a bit of help from Syed Abid Ali and Venkat, had bowled their hosts out for just 214. The one batsman to impress was Davis, unbeaten on 71 at the end. In the second innings he was promoted from five to first drop, and was unbeaten on 33 at the end of the third day as, on 150-1, West Indies had just managed to wipe out their first innings deficit. There was a freak accident on the fourth morning as a ball came through a net and hit Davis, necessitating a quick trip to hospital and seven stitches in a cut under the eye. Sadly a collapse followed, but not through any fault of Davis who was once more unbeaten at the fall of the last wicket, this time on 74.

For the third Test the teams moved on to Guyana and another draw. For Davis there were innings of 34 and 125*, but there was little in the pitch for the bowlers and the Indians easily batted out time. Moving on to Barbados for the fourth Test there was a similar result with Davis, as he had in Guyana, having the pleasure of the best seat in the house during a vintage Sobers century. The pair had added 170 at Bourda and this time it was a stand of 167. In the match Davis added innings of 79 and 22* to his tally.

The fifth and final Test saw the West Indies pressing hard for victory back at Port of Spain and a third major partnership (177 this time) between Sobers and Davis. The Indians were held to 326 in first innings before, thanks to 105 from Davis, the West Indians took a lead of 166. They were eventually left to chase 262 for victory. They gave it their best shot but, in the end, it was the Indians pressing, 96 runs on, for the last two West Indian wickets. Davis, coming in at eight, scored 19. He was left with a series average of 132.75, which he might reasonably have expected to be the best on either side. This was not, however, a normal series, a 21 year old Sunil Gavaskar averaging the small matter of 154.80.

A year later the New Zealanders visited the Caribbean for the first time, and there were five Tests scheduled. Neither side was very strong in bowling, so it was perhaps not so surprising that none of the Tests managed to produce a positive result. The first match, in Jamaica, saw local hero Lawrence Rowe make his famous double hundred on debut, 214, followed by 100 not out in the second innings. Davis scored 31 and 41. The West Indians always held the upper hand, but a double century from Glenn Turner and a century from future captain Geoff Howarth saw New Zealand to a draw without too many alarms.

The two teams moved on to Port of Spain for the second Test and this time it was New Zealand’s turn to hold a slight initiative throughout. Bev Congdon scored a big hundred for the visitors and for the West Indies Davis’ 90 and 29 were both important innings.

The third Test had a sensational start as, winning the toss and choosing to bat, the home side were reduced to 12-4 with Davis out for just a single. There was a slight recovery but 133 all out looked hopelessly inadequate as Congdon and Brian Hastings both scored centuries to take a lead of 289. West Indies did rather better second time round but when their fifth wicket fell at 171 defeat looked inevitable. At that point however the Sobers/Davis double act reprised its performances of the previous summer and added 254. After Sobers went for 142 Davis went on and on to a ten hour 183, and by the time he was eventually run out with his side on 544 the spectre of defeat was long gone.

The fourth Test in Guyana was spoiled in part by the weather, and in part by a nine hour opening partnership of 387 between Turner and Terry Jarvis in New Zealand’s first innings. The match petered out into a tame draw, Davis’ one visit to the crease bringing him a modest 28. The fifth Test the home side should have won, but in a relatively low scoring game, time again being lost to rain, the New Zealanders still had three wickets standing at the end after Ken Wadsworth and Bruce Taylor batted out the final hour and three quarters. For Davis there had been innings of 40 and 23, once more illustrating that he rarely failed, but had a habit of getting out after doing the hard work. His series figures were inevitably not as impressive as the year before, but he still had an average of 58.25.

At the end of the New Zealand series Davis was 28, and might have played Test cricket to the end of the decade, but as it was there were to be just two more Test matches. A lack of success heightened the tensions that always existed in West Indies cricket and there were real problems when the Australians arrived in 1972/73, the most serious of which was that Garry Sobers didn’t play. For the first three Tests Davis did not play either, much to the annoyance of Trinidadians. Davis himself was hugely disappointed, after all his recent success, to not even make the initial selection of 23 names.

At the start of the series the home side, now led by Kanhai, played pretty well but, having eventually selected Davis for the fourth Test after a narrow defeat there was a horrible batting collapse in the West Indies’ second innings, and defeat by ten wickets. Davis made five in the first knock and, in the second innings debacle of 109 all out he scored 16. In the final Test Davis scored 25 and 24 to help his side avoid defeat.

In 1973 West Indies toured England, with a series in the Caribbean due to take place the following year. By then however Davis had all but retired. He was said to be unavailable for the tour for business reasons, although the reality was rather more prosaic. The simple fact was that playing cricket for West Indies in those days paid next to nothing, and Davis needed a regular income, so he stayed behind.

At the time Davis was employed by the West Indian Tobacco Company. At the end of the New Zealand series he had been told that the company had it in mind to promote him to Sales Manager. There were strings attached however, as whilst the company did not mind Davis the District Sales Representative taking off as much time as he wanted to play international cricket, they could not be so indulgent with a Sales Manager.

Davis was given as much time as he wanted to mull the decision over, but when his name was not on that list of 23 he felt it was time to concentrate on his business career. He informed the company that he would not be touring again, and in return they agreed that if selected he would be able to play in home Tests although in the event he decided, after those two disappointing matches at the end of the series, to retire completely from international cricket.

As things turned out Davis did not stay with the West Indian Tobacco Company for too long, choosing to move into advertising with a company in which he eventually rose to become a director, but then health problems hit Davis hard.

First of all he suffered a freak injury in a football match in 1979. An eye was damaged by a goalkeeper’s finger and, despite treatment in the US and UK as well as at home in Trinidad, he lost the sight in that eye. Then in 1983 he was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. The cost of all his medical treatment took away the assets he had built up in his successful years in business.

Despite his sight problems Davis certainly could still spot a talented young cricketer and in the early 1980s insisted that his old friend Sobers take a look at a young man for whom Davis foresaw a great future, notwithstanding that the youngster was so small he could barely hit the ball off the square – there was certainly nothing wrong with Davis’ judgment of a player – the young man in question was Brian Lara.

Sadly the Davis marriage ended in divorce a few years after his MS diagnosis and for some time now he has been unable to live independently. Nonetheless he has astonished his medical advisers with his resilience. By all accounts he should be in a wheelchair, but he isn’t, and with the aid of a stick still manages to get himself out to a mall in Port of Spain for lunch with old friends two or three times a week. These days he can only manage a couple of hours at a time, but there is no self-pity, and his sense of humour is still intact, even if his wits are not as sharp as they once were.

Davis has two children, both of whom left Trinidad to go to University in the USA and did not return. Nonetheless Davis is still close to his 48 year old daughter and her family who live in New Orleans, and his 45 year old son who lives with his family in Tampa. All of them reunited in Trinidad five years ago for a seventieth birthday party for Davis, and despite his difficulties he still travels to the US as often as he can and is well looked after by the airlines who fly him there. The last 36 years have not been easy for Charlie Davis, but his stoicism in the face of adversity is perhaps exactly what is to be expected given the way he played his cricket.

Note – I began writing this feature several months ago. Davis’ cricket career is well chronicled but finding out anything of substance about his life outside the game proved difficult. In the end I was able to contact Bryan Davis, who was kind enough to fill in the gaps. I am most grateful to him.

Excellent and factual.

Enjoyable read. ⚓️

Comment by Frederick Archer | 7:52pm BST 18 July 2019

Excellent essay on a forgotten cricketer.

One minor correction.Close was not leading England at Lords in 1969.Illingworth was the captain.

Comment by AFZAL Ahmed | 7:31pm BST 11 August 2019