And the Moral of the Story is …………….?

Martin Chandler |

In the late 1980s and early 1990s in particular, although to a certain extent right through to the final flowering of Andrew Flintoff as a world class performer, all young English cricketers with any semblance of all-round ability found themselves compared to Ian Botham. The fact that it had taken over a century to find the first Botham seemed not to undermine the expectation of press and public alike that there would be a seamless transition to his successor.

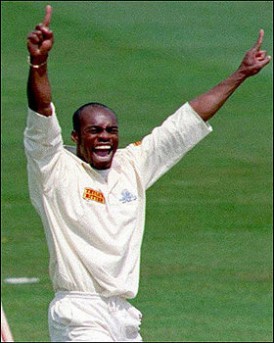

Chris Lewis was just one of those burdened with the Botham comparison. In fact he probably felt it more acutely than most. He was, first and foremost, a fine athlete with the physique to match. His athleticism in the field eclipsed that of the original Botham and, on occasion, his bowling touched the genuinely fast. More often, unfortunately, it was nearer to medium pace. As a batsman he looked the part, and some big innings at county level thrilled the crowds and raised expectations, but at international level he always appeared vulnerable, and never exuded the air of permanence that a true all-rounder would.

It is fair comment that Lewis’s Test career came at a time when England’s fast bowling stocks were low, and he undoubtedly would not have had so many opportunities in any other era. His debut came at the age of 22 in the final Test of the 1990 summer against New Zealand. Earlier in that season England skipper Graham Gooch had watched him blast an unbeaten 189 against his Essex side at Chelmsford. The sort of pitch the game was played on is best illustrated by the fact that Gooch’s side, replying to their visitors 520, lost just six wickets in piling up 761, but Gooch would have been impressed with Lewis’s bowling as well. He was the pick of the Leicester bowlers and stuck to his task to take 3-115 in 28 overs. His Test debut was a modest success too, but after that there were more lows than highs.

In 1992 he put in some good performances in England’s World Cup campaign, twice winning the match award before a disappointing personal performance in the final hastened England’s defeat. In the following year, his first and only Test century having been recorded in India, he was, with Alec Stewart, named as joint Cornhill England Player of the Year. Despite the award in that summer’s Ashes series he was dropped following the Second Test after being dismissed for a pair and taking 2-151 in Australia’s only innings.

Lewis’s absence was not however a lengthy one and he was back that same winter for the 1993/94 tour to the Caribbean and played in all five Tests, albeit with no great success. This was the tour where he missed the first match and had to spend two days in bed with sunstroke after shaving his head before going outside. The Sun famously dubbed him “the prat without the hat”.

Injuries as well as poor form cost Lewis appearances. He was a victim of migraine attacks, and variously missed out with back and hip injuries and, in his early career, with an uncommon blood disorder. His last Test was marred by what was, for many who mattered, the last straw. The final Test of the series against Pakistan was at the Oval. Lewis, who lived nearby, was given permission to stay at home rather than at the team hotel. He arrived late on the first morning, proffering a puncture as an excuse, but no apology. He scored 5 and 4 and took 0-112. He did get two more ODIs against South Africa two years later, but he achieved little in those and England never came knocking at his door again.

One of his coaches, Keith Fletcher, summed up the general feeling that lingers to this day Lewis had so much ability , but ultimately was not worth his place. He could bat and was a decent fielder, but he would always bowl better and quicker at people he thought he could dismiss. He rarely removed good players ………., a statement which does contain more than a grain of fair comment but, as with much of what Fletcher says about those he did not rate, is also an over-simplification. Lewis certainly did get good batsmen out when he was in the right mood. There cannot have been many bowlers who have, as Lewis did at Lord’s in 1996, dismissed Sachin Tendulkar twice in the same over (the first time was off a no ball). He later removed Rahul Dravid as well.

Englands next coach, David Lloyd, said of him, With Lewis the great problem was that you never knew quite what you were going to get, or even who you were going to get. That first summer I swear I had to handle two Chris Lewis’s. The first was brilliant against India, both in performance and attitude, but when the opposition switched to Pakistan …it was as if a different person turned up

Of his fellow players Michael Atherton, his England captain for the latter part of his career, said Like every other captain…..I fancied my chances of getting the best out of the enigmatic Lewis, and like every other captain I failed. I had expected to find a more sympathetic view in Devon Malcolm’s autobiography, and indeed he does offer insights as to where the England management, and indeed some teammates, failed to get to grips with a few aspects of Lewis’s personality, best described as “cultural” issues, but he still concluded No one seems to be able to get the best out of Chris Lewis, and he was unable to offer up any solutions, concluding I still rate his ability but can anyone manage to unpick the lock? Those words were written in 1998 and, of course, no one ever did.

By 1999 Lewis’ international career was over but the way he began the season suggested he was not prepared to accept that. Leicestershire’s first three County Championship fixtures brought him two centuries and 11 wickets and in that period he also recorded the only List A century of his career. Sadly for Lewis and Leicestershire injury returned to ruin the rest of his season, and then there was a decidedly bizarre episode in Lewis’ life in August of that year.

Lewis had, of course, been away from the England side for over a year, so he seems an odd choice for an Indian bookmaker to approach, however that is what happened. Shortly before the Old Trafford Test against New Zealand Lewis was invited to recruit England players to underperform and was given a budget of GBP300,000 with which to do so. More startlingly his potential employers told him that three of his former teammates had in the past taken money to influence the outcome of matches.

After the proposal was received Lewis went straight to the offices of the ECB and told them what had happened. There is some dispute about what happened next, although what is not in issue is that it took 17 days for the ECB to take the matter to the police. A similar report had been made to the New Zealand team management by Stephen Fleming. An approach had also been made to the Kiwi skipper although, seeing at an early stage where the discussion was going, he had quickly ended the conversation.

A thorough police investigation was carried out and many who were involved, whether directly or indirectly, were interviewed, including the two men who approached Lewis and Fleming. Mobile telephone records confirmed those contacts. The same records had also established that there were communications between the men and Brian Lara as well and, particularly significantly, with the London based Indian gentleman who was Hansie Cronje’s alleged paymaster. The businessmen’s account was that they were trying to arrange a benefit match in India and that the three cricketers were approached in the hope they would be able to put together a side to play in the match. They went on to say that their contact with Lewis was only as a result of their conversations with Lara and Fleming being unproductive. A file was eventually passed to the Crown Prosecution Service, but there was no prosecution.

The episode was not a happy one for either the ECB or Lewis. The former were at best indecisive, and at worst dilatory in their actions after Lewis made them aware of the approach. As for Lewis he felt let down by the board who he considered had treated him as a troublemaker and accuser rather than a player doing no more than carrying out their instructions to pass such information on. He never did receive the ringing endorsement from the ECB as to the probity of his conduct that he felt he deserved, although one of the investigating Police Officers later told journalist Simon Wilde that his behaviour had been “impeccable”.

The story originally broke in the now defunct News of the World shortly after the approaches were made, but it was later given new life by the emergence of “Cronjegate” and in April 2000, ostensibly on that subject, Lewis was interviewed by the same newspaper. That he was regarded as a pariah is evidenced by Darren Gough’s comments in his autobiography I resented the general suspicion now hovering over the entire England squad. Lewis was not flavour of the month with his former England teammates. A few days after the article appeared public opinion was reflected in the fact that Lewis was booed off the field at Old Trafford after being run out for a duck in a Benson and Hedges Cup game. Gough conceded in his book that he realised later he was wrong, but the story serves perfectly to illustrate why Lewis felt so let down.

Although he was only 32 the 2000 season marked the end of Chris Lewis’ First Class career. He played only five Championship games, although rather more List A contests, but it really was a case of going out with a whimper rather than a bang. A single sentence in the March 2001 edition of Wisden Cricket Monthly simply said that his contract had been terminated “by mutual consent”. The Almanack itself, in its 2001 edition, cited a degenerative hip condition, and underlined his poor performance in the season just gone. There was no fanfare and no thanks for past pleasure given. It is little wonder that Lewis came to believe that doing the right thing was not always the right thing to do.

So it was all over. A Test match career consisting of 32 appearances that had brought 1,105 runs at 23 and 93 wickets at 37 was, rightly, considered to be not good enough. That said it is worth noting that after 32 Tests, and just a year younger (27 as opposed to 28), Andrew Flintoff had scored 1,293 runs at 25 and taken 62 wickets at 41. Flintoff was undoubtedly fortunate to have the benefit of a more enlightened management team – who is to say that, had he been handled in the same way, Chris Lewis might not, in the final reckoning, have matched the great Lancastrian.

Although there was nothing like the money in the game for players then that there is now Lewis was still able to make a decent living from cricket. They did not run their full course but his agent negotiated lucrative contracts with Surrey and Nottinghamshire, and Lewis was able to drive a Mercedes convertable and to indulge his passions for designer clothes and the good life generally. His later career as a jobbing coach and club pro cannot have attracted anything like the same rewards and perhaps that, rather than any inherent criminogenic characteristics, is what led to his final demise. First however there was to be one more burst of positive publicity for Lewis.

At the beginning of the 2008 season a surprise announcement came out of the Oval that Lewis, by then 40, had signed for his former county to play in T20 matches. It was expected that he would have a bit of time to get up to speed before the hit and giggle started, but a rash of early season injuries amongst his bowling colleagues meant that he was pressed into service in April for Surrey’s opening Friends Provident Trophy game against Middlesex. It was to be no fairy tale return as the Middlesex batsmen in general, and Andrew Strauss in particular, gorged themselves on some innocuous bowling. No wicket for 51 in just six overs was Lewis’s disappointing return, and while a brisk 33 with the bat hinted at better things to come the game was already over as a contest before he got to the crease. Injury permitted but a single, even more disappointing, T20 appearance, and after that the great comeback was over.

Later that year, together with former London Towers basketball star Chad Kirnon, Lewis visited the Caribbean idyll of St Lucia. On their return a routine check of the luggage of both men at Gatwick disclosed cans of fruit and vegetable juice. Unfortunately however all was not as it seemed and analysis confirmed that the contents were dissolved cocaine with a street value of approximately GBP140,000.

Both men pleaded not guilty their defences being that they did not know that they were carrying a controlled drug. By implication, and later in their evidence, both men effectively blamed the other. As with nearly all cut throat defences the jury had little difficulty, after an eight day trial, in convicting both men. The Judge at Croydon Crown Court wasted few words on the two disgraced sportsmen branding them cowardly and avaricious. Applying the relevant sentencing guidelines saw them each receive a 13 year custodial term. Lewis will be 47 when, in June 2015, he is released on licence, and his remaining ability to earn a living, from the only thing he really knows, will be compromised to say the least.

With a conviction for a serious drug trafficking offence now on his record it is tempting to look back on the “match fixing” approach and wonder if perhaps there is more to it than was originally thought. When all is said and done any dealer in Class A drugs clearly has few, if any scruples about how he makes his money, and could not be expected to have any qualms about defrauding the gambling fraternity. But I have to say I am not convinced. There is no doubt in my mind that the jury who, after those eight days of evidence and speeches, decided Lewis knew exactly what he was carrying on that flight, were correct, but I suspect the actions were those of a desperate man backed into a financial corner rather than an evil one. I say that having had the benefit, sadly all too fleeting, of speaking to Lewis back in 2006, or was it 2007?

Naturally I recall some aspects of the case vividly, and others rather less so. I cannot, for example, now remember the name of the young man concerned, nor the details of the assault he had carried out on a fellow pupil at his school, but in any event I was instructed to represent the lad in our local Youth Court. He came from the sort of hard-working family who you would never expect to see near a courtroom, but despite their obvious shame they were hugely supportive of a son who, in fairness, was not without some fairly serious issues, cruel mockery about which had led to the incident which brought him before the court. Family apart the lad did not have a great deal going for him in life, apart from his cricket. He was tall and slim with the sort of physique that was made for bowling fast and Lewis was his coach. His father explained to me that Lewis was a great man, who had gone way beyond what he was contracted to do in order to help his son develop, both as a man and as a cricketer.

I spoke to Chris Lewis, who was desperate to help in any way he was able to and was quite happy to come to the court to give his support. I, of course, hoped that he would do so, but I had to be frank with my client and explain that he had so much mitigation that even an old hack like me was not going to have any difficulty in securing for him the most lenient sentence the court could impose, and that the last thing that sentence would do would be to impinge on his cricketing committments. In the face of that advice Dad, as was typical of the man, was not prepared to inconvenience a former international cricketer, even one who was happy to oblige. So I never did meet Chris Lewis, but he certainly seemed a thoroughly decent man to me.

Great read. Would make a decent script for a movie too.

I remember Lewis being a great athlete and a cricketer capable of far more than what he eventually achieved. There was something very lithe and serpentine in his run up to the crease when he was bowling well. Too few of those occasions unfortunately.

Comment by Arachnodouche | 12:00am GMT 9 December 2011

Think Lewis himself said that because he looked lithe and effortless that people expected him to be better than he was. I tend to think his problem was one of mental fortitude but it’s a good point about the coaching regime at the time (or lack of it). Wonder how Ramprakash, Hick and Lewis may have got on under Flower or Fletcher?

Comment by keeper | 12:00am GMT 9 December 2011

Very good read, as ever. Still sort of feels the Clairmonte Christopher Lewis story is somewhere near the end of act two tho; whether act three is redemption or further downward spiral depends upon the principal player I suppose.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 10 December 2011