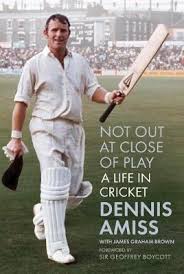

Not Out At Close of Play

Martin Chandler |Published: 2021

Pages: 224

Author: Amiss, DL and Graham-Brown, JMH

Publisher: The History Press

Rating: 4 stars

Two days after this review appears Dennis Amiss will celebrate his 78th birthday. It is unusual for a man of his years to write an autobiography, or indeed to produce a second such book 48 years after his first attempt at the genre. In fact had it not been for a certain Mr ER Dexter and last years 85 Not Out (that came along 54 years after Ted Dexter Declares) Amiss might have been a record breaker. It is perhaps therefore just as well that, unlike his famous England opening partner who provides a foreword to Not Out At Close Of Play, statistics for their own sake were never what motivated Amiss.

One of the 25 men to have made a century of centuries Amiss has always come across as a dedicated professional and a good role model, impressions that his book does nothing to dispel. The writing duties have been undertaken by James Graham-Brown, a man whose name I recognise as a fringe player for Kent and Derbyshire in the 1970s. Graham-Brown went into teaching and, now retired from that profession, has become an accomplished playwright. I believe this is his first book, and I hope it will not be his last.

Where Amiss is exceptional is in the length of his career. He joined Warwickshire in 1958 as a 15 year old and retired in 1987, so he spent one shy of thirty years at Edgbaston as a player. Also unusual, for a batsman who went on to achieve so much, is the length of time it took Amiss to establish himself, first in the Warwickshire side and then with England.

In fact it takes the major part of half of Not Out At Close Of Play for the narrative to reach the point where, in Pakistan in 1973, Amiss finally managed to cement his place in the England team. The book is not, unlike a number of recent cricketing autobiographies, in any way about mental health problems as such but the the reflections of a septuagenarian on the cause of the disappointments and frustrations of his early years are fascinating, and the strength of his memories of second eleven and other minor matches from so long ago are impressive.

His success in Pakistan meant that at the start of 1973 Amiss joined Geoffrey Boycott in their productive partnership at the top of the England batting order. His account of their first match together, more particularly how he ran Boycott out in the second innings and the latter’s reaction to that dismissal is an amusing one, and a story which Boycott, perhaps curiously, chooses not to give his side of in that foreword.

Amiss tells his story in a straightforward chronological manner. He naturally dwells on the highlights of his playing career, those two double centuries against West Indies, although he certainly doesn’t seek to do anything other than accept that, overall, his record against Australia in general and Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in particular was disappointing.

Much has been written by many about the Test cricket in the 1970s and whilst, as he was an active participant, I was certainly interested in Amiss’ views on that subject the two aspects of his career that have not been the subject of much previous writing are his roles in World Series Cricket and the first rebel tour to South Africa. The latter in particular is an episode that seldom features in print, none of the participants being willing to share their thoughts with Peter May in 2010 when he wrote The Rebel Tours.

Not being one of the star turns in WSC Amiss’ route to Kerry Packer’s band was a different one to many of the other players who signed up for the ‘circus’ and his views on it are well worth reading even if they are if unsurprising. Most interesting is the reaction he experience in dressing rooms and the corridors of powers after he got back from Australia in 1978. That there was much disapproval in the committee rooms is a given, but there also seems to have been hostility amongst fellow players. It is slightly disappointing that details of that are sparse, and whilst I can understand why, more than forty years on, Amiss does not want to name names I would like to have known more about the ‘discussions’ that took place.

Given the political and ethical considerations the South African trip was a very different proposition. To be fair to Amiss the issues are tackled, but Amiss’ personal justification for going on the tour is fairly predictable and rather suggests the chapter is included not because Amiss wants it to appear, but because he realises it has to. As Amiss is clearly a man who thought long and hard about what he did with his life and career that particular chapter could have been more interesting had Graham-Brown drawn out from Amiss what his views were and are on the counterarguments.

At the end of the day however nothing detracts from a reader’s enjoyment of Not Out At Close Of Play, particularly those of us who are old enough to have followed Amiss’ career and can remember the genuinely decent bloke he was. That he still is comes across very clearly in his book, which no one comes out of badly despite the various travails in Amiss’ playing career and his having had to involve himself, in carrying out the various administrative roles he fulfilled for county and country between 1993 and 2011, in some of the trickier situations in which English cricket has found itself.

For some, this reviewer included, the book would have benefitted from rather more in the way of statistics than the rudimentary figures that appear on a single page at the end of the book, but there is a good index and an interesting selection of photographs so, all in all, Not Out At Close Of Play is highly recommended.

Leave a comment