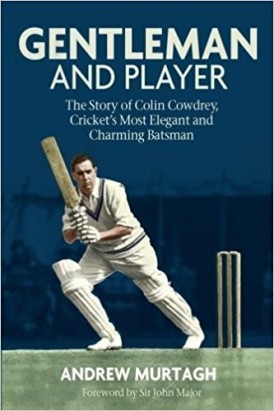

Gentleman and Player

Martin Chandler |Published: 2017

Pages: 352

Author: Murtagh, Andrew

Publisher: Pitch Publishing

Rating: 4 stars

There were two autobiographies from Colin Cowdrey in his lifetime, and another of that ilk that he had not yet completed when he died in 2000 at the age of 67. The first, Time For Reflection, appeared in 1962 at which point Cowdrey’s career had more than a dozen years to run. It isn’t very good. Later, shortly after he retired from the game in 1975, we had MCC: The Autobiography of a Cricketer. As such books go it is certainly one of the better ones, but not of much assistance to anyone who really wanted to know what made Cowdrey tick.

The first biography of Cowdrey was written by Ivo Tennant and appeared in 1990. The title, The Cowdreys, suggests it deals with the lives of sons Graham and Christopher as well as Colin. Looking at the book, which I must admit to not recalling ever actually reading, it does however seem to deal in the main with Colin’s career.

In 1999 Mark Peel, a schoolmaster, wrote what he described as an unauthorised biography of Cowdrey, although he did have some assistance from his subject and eldest son Christopher. The Last Roman isn’t a bad read, but certainly left the way open to Andy Murtagh, like Peel of the schoolmasterly persuasion, to write the definitive life of Lord Cowdrey of Tonbridge. With the full support of all four of Cowdrey’s children, and access to all of his extensive personal archives no one will have a better opportunity.

Since retiring from Malvern College, Murtagh has put his time to good use writing, in a slightly quirky and individual style, lively biographies of George Chesterton, Tom Graveney, Barry Richards and John Holder before tackling Cowdrey. The fact that, unlike with the other four, he was not able to interview his subject has not prevented him adopting his usual conversational style in relation to the many contributions obtained from friends, family and contemporaries of Cowdrey, and indeed on occasion the man himself speaks via his unpublished writings.

It is more than forty years now since Cowdrey retired from the game after a First Class career that had lasted for more than a quarter of a century. He was a fascinating man, his background very much a throwback to the days of empire, and a true gentleman amateur. He was also, despite his famous pear shaped physique, a multi talented sportsman and, with the willow in his hands, one of the most stylish batsmen the game has seen.

Murtagh looks fully at Cowdrey’s childhood in India followed by his stirring deeds for Tonbridge as a schoolboy. In 1954/55 he was taken to Australia as a 21 year old. He was not expected to figure in the Tests but in the event played in all five. His average was a fairly modest 35, but it was a low scoring series and an acclaimed century at Melbourne in the third Test firmly established Cowdrey as a Test batsman. Murtagh’s account of the tour itself is a good one, but it was something that happened before the partly left England that really caught my eye. I had never before read that Douglas Jardine made his way to Tilbury to bid farewell to Hutton’s men, still less that he had a few words of advice and encouragement specifically for Cowdrey. I would love to know the source of the story – the source is certainly not mentioned Gentleman and Player.

One of the most significant controversies in which Cowdrey was involved, as the incumbent England captain, was the D’Oliveira Affair. There seems to be little doubt that the selectors’ initial decision to omit D’Oliveira from the party to tour South Africa in 1968/69 was influenced by political considerations, but although many have searched for the evidence it must be unlikely now that the whole truth about the selector’s deliberations will ever emerge. Murtagh sheds little new light on this important corner of the game’s history although, unlike any previous writer on the subject, he did manage to explain to me ‘the party line’ and left me wondering, for the first time ever, whether perhaps there really is nothing more to tell.

Anyone with little more than a passing interest in Cowdrey’s life will know something of his travails with the England captaincy. It was a job he always wanted but never got a decent run at. He was Peter May’s deputy back in the late 1950s and did a good job when he had to take over. What Cowdrey really wanted to do was take a side to Australia, but he somehow got behind Ted Dexter and then MJK Smith in the pecking order. Later, after Brian Close contrived to lose the job for ‘non-cricketing reasons’ Cowdrey got another chance. He did well, winning in the West Indies in 1967/68, but in 1969 his Achilles tendon snapped and he missed a season, and Ray Illingworth made the job his own.

In 1970/71 under Illingworth, with Cowdrey vice-captain once more, England regained the Ashes on Australian soil for the first time since the days of Jardine and Bodyline, almost forty years previously. Cowdrey was a lost soul in the series, aggrieved at not leading the side, disappointed by the tough and uncompromising way the game was played and sadly out of form. The depth of his misery is best illustrated by the fact that such a significant cricketing event takes up less than a page of MCC: The Autobiography of a Cricketer.

There is certainly no attempt by Murtagh to avoid 1970/71, and he has a good look at the Illingworth/Cowdrey relationship. But I have heard, from a normally impeccable source, that Cowdrey had other troubles that winter. There is no mention of those at all, which means that either my source is not as reliable as I think, or alternatively there are still one or two aspects of Cowdrey’s life that are being kept under wraps. I suspect it is the latter, but that doesn’t alter the fact that Gentleman and Player is an excellent book and one which, like its predecessors, is a credit to the diligent research of its author and his ability to breathe life into his writing. The book also boasts a fine selection of photographs, which goes most of the way to earning forgiveness for the lack of an index, the absence of any statistics and a couple of rather grating typographical errors.

Leave a comment