Wilfred Rhodes – A Good Utility Player

Martin Chandler |

To every cricket follower of my father’s generation that I spoke to Wilfred Rhodes was Yorkshire personified. He was grumpy, taciturn and did not suffer fools gladly. One long time colleague said of him; He was not a lovable man; he was often critical to the point of rudeness before adding a rider, although his criticism of players was never far from the truth.

Sydney Barnes was not a Yorkshireman but, in many ways, was cut from the same cloth as Rhodes. They played for England together before the Great War and in retirement were frequent companions. Barnes view of Rhodes was that he was a well-informed man, very straight in his speech and all his dealings. He could be rather cynical at times, but he was one whom a man would be proud to call a friend.

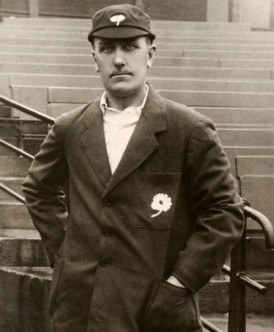

The reputations of both Barnes and Rhodes are reinforced by one thing that they have both given the game’s historians, that being the challenge that one faces if he or she is asked to find an image of either of them smiling. Theirs was a time when most photographs were posed, so they usually had a chance to put their best face on, but they didn’t. Smiling cricketers were not unknown however, by way of example Rhodes’ long time partner at Yorkshire, George Hirst, was often photographed with an impish grin on his face.

Like Hirst Rhodes was born into the small Pennine community of Kirkheaton in 1877. Always a fine cricketer he was an all-rounder then but not, initially at least, a spinner, preferring to bowl at something above medium pace. He was soon playing for the village team, although his employment as a railwayman in the sheds at Mirfield station caused some problems with that. Rhodes had to work on Saturdays until 2pm, which gave him just half an hour to get to wherever he was playing cricket at 2.30pm. One day he rang the bell at 1.30pm, and that was the end of that employment.

The eighteen year old Rhodes then left West Yorkshire to travel to Scotland, having secured much more congenial employment as a professional for the local club at Galashiels. He had sought a post nearer home, but had been turned down on the basis that he was too young. To begin with Rhodes continued with his seamers whilst north of the border, but changed style after the first of his two years there.

The Scottish season finished earlier than that in Yorkshire so Rhodes got home in time to help Kirkheaton to their Championship. He made the decision to change his pace and become an orthodox slow left arm bowler, something he had only experimented with in the past. He spent the winter in a barn next door to his home, bowling at a wall for hours on end. The ball he used was painted white on one side, so he could watch the spin.

Had they been able to afford him Rhodes might have joined Warwickshire, who he impressed during a trial, but as it was he went back to Yorkshire who arranged for him to join the Sheffield United club for 1898. At this stage Yorkshire were in need of a replacement for Bobby Peel who had been dismissed the previous summer. The story goes that Rhodes was in competition with Albert Cordingley to replace Peel, and indeed it seems that Cordingley was in pole position, his having played for the county against the Colts side the previous September. Rhodes appeared for the Colts against the county that day, and had had rather less success than Cordingley. The following May the plan was, apparently, that Rhodes would get the first game of the 1898 season against MCC at Lord’s, and that Cordingley would then play against Somerset at Bath in the first County Championship fixture of the summer.

The MCC side was captained by WG Grace and, later, Rhodes said that bowling to the great man then was the only time in his career that he felt truly nervous. Yorkshire overcame a strong MCC side, and there were six wickets in all for Rhodes so he enjoyed a decent debut. It is at this point that fate intervened. News reached the Yorkshire party of the ill-health of Cordingley’s mother, and he had to return home. Had he not done so and taken his place at Bath then it might well have been Cordingley who had taken advantage of the drying turf to end up with match figures of 13-45 in a convincing victory. But it was Rhodes who had the pleasure, and he never looked back and ended the campaign with what will doubtless remain in perpetuity the greatest ever haul of wickets by a man in his first season, 154 of them at 14.60. Those numbers also made Rhodes the most successful of Yorkshire’s regular bowlers and, more importantly, helped a side who had been fourth the year before to the title. Wisden has never been prone to hyperbole, particularly in those far off days, but its 36th edition certainly waxed lyrical about the county’s new slow left arm bowler, even going so far as to describe Rhodes as a sensation.

Through the course of his career Rhodes sent down more than 185,000 deliveries. No bowler in history has got within 10,000 of that total. The renowned Yorkshire journalist and author Jim Kilburn described his bowling thus; No action stays more clearly in the mind than his, with his three easy steps to the crease, the smooth cross-over, the gentle circling of the arm and the moment of immobile watchfulness as the batsmen furrowed his brow. Every over by Rhodes was a creation of beauty.

He wasn’t a big spinner of the ball, but at the start of his career turned the ball more than he did later on, by which time he was a master of subtle changes of flight and direction. There were some who suggested that in his later years he barely turned the ball at all, a comment that brought the famous retort, if t’batter thinks it’s spinnin’, it’s spinnin’.

Rhodes’ second season was marked by a visit of the Australians and some superb early season form carried him into the Test side. The game was drawn and Rhodes’ debut marked the final Test appearance of the England captain, WG Grace. The combined First Class careers of Grace and Rhodes stretched for 65 years. There were seven wickets for Rhodes, and he got three more in England’s ten wicket defeat at Lord’s. He was then left out of the next two matches before returning for the final Test and taking three more wickets. It would be a decade before Rhodes was next left out of an England side against Australia for which he was available. At the end of that 1899 summer Rhodes left an indelible mark on his career at the end of the season when playing against the tourists at the Scarborough festival. In Australia’s first innings he took 9-24, figures that would still be his career best 30 years later. At one point there was a spell of 7-5.

In 1899 Rhodes batted at ten or eleven, and was considered very much a specialist bowler. There had been three half centuries for Yorkshire in that debut season, but only one in 1899. The following year was Rhodes’ best with the ball, he took as many as 261 wickets at 13.81. There were another three fifties in his best season yet with the bat and, by 1903, he had managed 1,000 for the first time and the first of his record 16 doubles.

In the meantime Rhodes had played a famous role in the memorable series of 1902. The first Test was drawn when the final day was rained off but that was not before Rhodes had contributed an unbeaten 38 from number 11, the main point of which was that it enable England to occupy the crease until a wet wicket started to dry out. That characteristically gritty display was followed with 7-17 and, with a little help from his fellow resident of Kirkheaton, Hirst, Australia were dismissed for 36. It was with Hirst again that Rhodes made his other great contribution to that series when they put on 15 for the last wicket to drag England over the line in the final Test. They didn’t ‘get ‘em in singles’, and neither man could recall any words to that effect being uttered, but it remains the best known story involving Rhodes.

In those early days opinion was sharply divided over the division of Rhodes’ labours between his batting and bowling. Lord Hawke, the man in charge of Yorkshire cricket in that era, was firmly in the latter camp; Time after time I used to say to him, now Wilfred, you are not to get more than 20. Initially Rhodes said nothing, but did eventually respond; I hope that one day I should be played for England for my batting. The transformation was inevitable given Rhodes expressed view; I liked to feel the bat in my hand, and if anyone had asked at any time in my career whether I enjoyed scoring 50 more than taking half a dozen wickets, I should’ve said ‘yes I do’.

As far as what sort of a batsman Rhodes was Kilburn wrote; He was a careful batsmen. In the modern idiom he played the percentages, calculating profit against risk in his selection of strokes. His innings were investments before speculations, he preferred gilts to equities. No one attended a cricket match specifically to see Rhodes bat but crowds and colleagues alike noted with admiration the competence and assurance with which his scores were built.

The winter after his first double Rhodes made his first trip to Australia with Plum Warner’s side. He had not gone with Archie MacLaren’s side two years previously as Lord Hawke had not wanted either him or Hirst to travel, anxious that they should be able to give their all for Yorkshire the following summer. Two years on and the MCC had finally taken responsibility for the Test side, and Hawke did not feel able to raise the same objection.

Warner’s men recovered the Ashes, and indeed it was as a result of this success that the use of the urn as the notional trophy for success came back into vogue after twenty years. There had been fears voiced that Rhodes would find that the hard wickets of Australia would not allow him to bowl as effectively as the softer English pitches. It was neither the first or last time that the value downunder of a top class English finger spinner would be questioned and, not for the last time, the doubters were proved wrong. Rhodes took 31 wickets at 15.74 in the five Tests and was comfortably the best bowler on either side. In the second Test at the MCG he took 7-56 and 8-68, still the eleventh best Test analysis of all time and, at the time, the best in an Ashes encounter.

With the bat Rhodes was very much a tailender still, although in an injury crisis he did open, without conspicuous success in the final Test. Before that however he did, from number eleven, involve himself in a famous record in the first Test. His partner was ‘Tip’ Foster, who completed an innings of 287, which remains the highest ever score by a debutant by a comfortable margin. Rhodes helped Foster add 130 for the final wicket, and contributed 40. That lasted as a world record for almost 70 years, and the English record survived intact until two years ago, when it finally fell to Joe Root and Jimmy Anderson against India at Trent Bridge.

As a bowler Rhodes performances had peaked, and by the time he got to Australia a second time, in 1907/08, he was batting in the lower middle order. He was an automatic choice for an understrength England side that lost 4-1, and indeed might easily have been beaten in the match they managed to win. For Rhodes there was just a single fifty and seven expensive wickets.

Australia returned to England to defend the Ashes in 1909. This was the first season in which Rhodes topped 2,000 runs. For Yorkshire he was still a frontline bowler, 141 wickets at 15.89 are testament to that, but after a decade he was omitted from the England side for the second Test. By now the selectors first choice left arm spinner was Kent’s Colin Blythe but, in a difficult summer, Rhodes’ exile lasted just the one Test and he was back for the third match of the series. In the fourth Test he showed he wasn’t quite finished and outbowled Blythe in the second innings, taking 5-83, but the match was still drawn. The sign of things to come was the fifth Test when Rhodes was picked primarily as a batsman, and he responded with innings of 66 and 54.

That winter Rhodes went to South Africa for the first time. The matting wickets clearly didn’t suit him, and he took just two wickets in a series in which England’s leading bowler was George Simpson-Hayward, the last lob bowler to play international cricket. With the bat Rhodes opened in all five Tests. He averaged 25 and twice posted a half century, but overall it was a disappointing trip for him and England, who lost the series 3-2.

For the remaining pre-war seasons Rhodes bowling declined further, so much so that in 1912 and 1913 he failed to take his hundred wickets for the season. He continued to progress with the bat however and in 1911, on the eve of his third trip to Australia, he had his best ever season’s tally with 2,261 runs. In Australia Rhodes more than fulfilled expectations with the bat as he formed a formidable opening partnership with Jack Hobbs. It was a series in which England took back the Ashes in style. The bowling of Barnes and Frank Foster are rightly remembered as the major factor in the win, but in truth Hobbs and Rhodes were just as crucial. When Hobbs opened in the first Test with the long forgotten Sep Kinneir of Warwickshire they lost comfortably.

England won each of the next four Tests. Promoted to open Rhodes scored 463 runs at 57.87 including a century and three fifties. Hobbs was even more prolific, his tally being 662 at 82.75 with three hundreds. As a partnership their finest hour was at the MCG in the fourth Test where they put on 323, still England’s highest ever opening partnership. Rhodes’ success was solely with the bat. In the entire series he bowled just 18 wicketless overs.

When war broke out in 1914 First Class cricket came to a halt. Rhodes the batsman and support bowler was 36. His war work was in a munitions factory and in addition he played league cricket. For a time it was uncertain whether county cricket would ever be played again and when the war did end Rhodes was 41, and received a tempting offer from the Lancashire League. The decision was made that there would be a County Championship for 1919 comprising two day matches, something which didn’t much appeal to Rhodes, but his county needed him. Before the war the county’s bowling looked to be in the safe hands of two young all-rounders, Major Booth and Alonzo Drake, but Booth died on the Somme and Drake of ill-health on the eve of the 1919 season.

The 1919 version of Rhodes was therefore required to bowl. The strength and suppleness of the fingers was not quite as of old, and as noted some of the powers of spin were gone, but none of the nous and experience. He might not have liked the two day game, but he took 164 wickets at 14.42, his best summer since 1907. There were more than 1,000 runs as well, if not as many as in the pre-war years. He did even better in 1920. There were three fewer wickets, but the cost was just 13.18 and there were 1,000 runs again. He was an obvious choice for the 1920/21 trip to Australia, his 43 years notwithstanding.

Amidst England’s 5-0 defeat and the chaos of the following series at home in 1921 Rhodes was as nonplussed as anyone by the pace of Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald. He attempted, without any real success, to counter the pace by switching from his classical method to a two-eyed stance. In Australia he had just a single half century and an average of 23.80 and he was dropped after the first Test of the return series as the selectors embarked on a game of musical chairs that saw as many as thirty men play in at least one of the Tests. Four wickets in Australia at more than 60 runs apiece did nothing to ease the disappointment Rhodes’s batting caused him.

His post-war Ashes ventures might have been a chastening experience for Rhodes, but at county level he was still a formidable all-rounder and in the next five seasons produced four doubles. By now he was the de facto captain of Yorkshire as well. Nominally the county followed tradition and appointed an amateur batsman who was often of no more than good club standard, but the real power behind the throne was Rhodes. One of the best known stories is of an occasion when the man who the scorecard said was Yorkshire’s captain was padding up ready to bat, only to be told by one of his teammates not to bother as Wilfred will be declaring at the end of the over. On another occasion, with Yorkshire trying to turn the screw in the field Rhodes invited the captain to field at long off, on the basis that he should be spared the strong language.Much as Yorkshire were reluctant to fly in the face of convention Lancashire titles in 1926 and 1927 were doubtless a factor that turned White Rose minds to the desirability of a captain who earned his place on merit, and in November 1927 Herbert Sutcliffe was offered and accepted the captaincy. Rhodes was 50 at the time and there is no evidence he had any concerns about serving under Sutcliffe but, not for the last time, the Yorkshire members were not happy and the groundswell of opinion wanted Rhodes rather than Sutcliffe, or better still an amateur, coupled with it being revealed that only a narrow majority of the cricket committee were in favour of Sutcliffe, led the great opener to change his mind, and it would be more than thirty years more before a paid player finally did lead the White Rose.

In the international game, as the 1926 Ashes series dawned it was the best part of 15 years since Rhodes had been part of the last victorious England side. By now 48 he was, with Sutcliffe, invited to join the England selectors. After four draws those selectors decided to relieve Notts’ skipper Arthur Carr of the captaincy in favour of the Kent youngster Percy Chapman. His colleagues also wanted Rhodes to play and, not without serious misgivings, he eventually agreed. Thanks in large part to a famous stand between Hobbs and Sutcliffe on a sticky wicket England won, but Rhodes the bowler played an important role as well. In the first innings his figures were 25-15-35-2, his victims Bill Woodfull and Arthur Richardson. The stranglehold continued in the second innings when, with a young Harold Larwood, he helped dismiss Australia for 125, his contribution this time being 20-9-44-4. Again his victims were frontline batsmen; Bill Ponsford, Warren Bardsley, ‘Horseshoe’ Collins and Richardson again.

It might reasonably have been assumed that that would be the end of Rhodes in Tests, but in fact there were four more caps to come. In his 52nd year Rhodes was a member of the party that toured West Indies for the first ever series in the Caribbean. The brightness of the sun was no help to a man whose eyesight was just beginning to deteriorate, and he scored only 51 runs. With the ball he bowled 256 overs, and all the old guile was there and he went for less than two runs per over, but the ten wickets he took cost more than 45 runs each.

The final season of Rhodes career was 1930. He scored fewer runs than in any summer since 1899, but did record an unbeaten 80 against Notts at Trent Bridge. There was no Larwood on show for the home side, but Fred Barratt, Bill Voce and Sam Staples were all Test players. Bowling opportunities were limited that final summer by Rhodes having to share the stage with his successor, Hedley Verity, but the old man still took 73 wickets at less than 20, and as importantly knew that he had left his role in safe hands. The last of Rhodes 1,110 First Class matches was for a scratch eleven raised by ‘Shrimp’ Leveson-Gower for a game at the Scarborough Festival against the 1930 Australians. Rhodes finished with 5-95. Bradman was Australia’s top scorer with 96. Bob Wyatt put down a straightforward catch from the Don before he had scored, and he was dropped twice more, all from Rhodes’ bowling, so the old man’s sign off might have been even better.

Deteriorating eyesight afflicted Rhodes after retirement but the last cricket he played was as late as 1949 when he was 71. He could just about make out the batsman 22 yards away, but could certainly not see the wicket. He bowled from memory however, and could still drop the ball on a length, and fittingly the last over he bowled in any form of cricket was a maiden to recently retired Yorkshire skipper Brian Sellers. As Kilburn once wrote of Rhodes; He might sometimes have bowled unsuccessfully, but never badly.

Even the complete loss of his sight did not put Rhodes off the game, and he was still a regular attender at big matches even when in later life he moved to Bournemouth to live with his only daughter. His ability to ‘see’ what was going on in the middle is illustrated well by one story, an occasion when he admonished one of his successors, Don Wilson, for bowling too short. Understandably perplexed at how the old man worked that out Rhodes explained; I can tell where they hit the ball when I hear the fieldsman’s feet, especially when they hit it in my direction, and they hit it in my direction too often. It means they’re square cutting and a slow bowler should never be square cut or pulled.

Having survived his wife of 50 years Wilfred Rhodes outlived his daughter too and he spent his last three years in a Dorset nursing home before he died in 1973 at the grand old age of nearly 96. He spent his life describing himself as a good utility player, but no star. He took around 4,200 wickets depending on whether you prefer traditional figures or revisionist ones, and all but 40,000 runs. No one will ever get close to that tally of wickets, and only sixteen men in the history of the game have scored more runs – not bad for a mere utility player.

Leave a comment