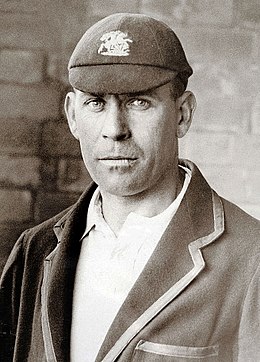

Patsy

Martin Chandler |

He was christened Elias Henry Hendren, but few sources refer to EH Hendren, and no one ever called him Elias anyway. His teammates, in light of his Irish ancestry, called him ‘Murphy’, and his partner in so many major partnerships, ‘Young’ Jack Hearne, called him ‘Spud’. To the vast majority of people however he was simply ‘Patsy’, very possibly the most popular cricketer ever to have played the game.

Everybody liked Patsy. No one seemed to have a bad word for him and the warmth with which his name is mentioned is universal. That affection extended well beyond England. Patsy was well liked in Australia, and a caricature of him one of the favoured tools of Arthur Mailey. The much respected Australian Prime minister Robert Menzies described him as a warm-hearted human being who embodied and displayed the true character of cricket. England teammate Jack Hobbs wrote I do not know a more popular man, and Sir Pelham Warner referred to a lovable personality and a man who raised the status of the professional cricketer.

The importance of the name of Patsy Hendren stretched as far as India. In 1946 there had not been too many cricket books published in India, and of those that had appeared as far as I am aware all had Indian authors. One of them, SK Roy, decided to publish a book on Indian cricket and, presumably having met Patsy on the 1946 tour, persuaded him to put his name to it. Patsy had never played in India, and as far as I can tell had never visited the country, but such was his reputation that he was still entrusted with Cricket Musings, published in Calcutta in 1947.

Born in 1889 in Turnham Green in Middlesex, Patsy’s early life was frequently struck by tragedy. The loss of two brothers, a sister and both parents meant that he and his younger brother John were effectively brought up by their older brother, Denis. All three were talented sportsmen. Denis played for Middlesex between 1905 and 1907, although he never quite made the grade. Later he played for Durham and, just once in 1919, turned out with Patsy for Middlesex after the Great War. The brothers were unbeaten at the end of the match after putting on 24 for the seventh wicket to secure a draw. Denis went on to become a First Class umpire and stood between 1931 and 1957. John might have made it a hat trick of Middlesex players as, when the Great War ended the game in 1914, he was playing for the second eleven. In 1916 however, just 23 years old, he fell in the Battle of Delville Wood.

An all-round sportsman as a teenager Patsy played professional football for Brentford and neighbours Queens Park Rangers before moving to Lancashire and Manchester City where, still only 20, he played twice in the old First Division. Transferred the following season to Coventry City the diminutive (Patsy was only 5 feet 5 inches in height) winger played in 23 First Division matches scoring ten times. Injury then kept him out of the side the following season and he ended up back at Brentford in the old Southern League. After the War Patsy played regularly in the old Third Division (South) until, by then nearly 38, he hung up his boots in 1927. The pinnacle of his football career was an England Cap against Wales in 1919. It was not a full international, so like Denis Compton a generation later Patsy was not a true double international, but it is an impressive achievement nonetheless.

As a cricketer Patsy was a slow starter. He was always a fine fielder, whether in the slips or in the outfield, and his earliest matches for Middlesex were occasions when he was selected with those skills in mind as much as his batting. From his debut in 1907 it was four years before the first century came, and although he finally started to make strides in 1913 and 1914 at the outbreak of War Patsy’s batting record was no more than ordinary, 5,636 runs at 27.49. His war was relatively quiet. He joined the Army almost straight away but after months of training he was sent back to civilian life. After leaving school he had been an engineer, a job he had cared for very little, but his abilities in that field were now considered more important than military service. In time those priorities changed again and Patsy signed on once more in 1917.

When the First Class game resumed in 1919 Patsy was already 30, but there were almost 52,000 runs at 55.94 to come and as many as 164 centuries. When he finally called it a day at 48 he was the third highest run scorer of all time behind Hobbs and Frank Woolley, a position he retains and doubtless always will. That first post war summer, despite the unsuccessful introduction of two day matches in the Championship, saw Patsy’s average north of 60, and it stayed there the following summer when he totalled more than 2,500 runs for the first time. To add to his pleasure Middlesex won the title in both seasons and Patsy’s selection for the Ashes tour of 1920/21 was a formality.

Overall Patsy batted well in Australia. He averaged more than 61 and scored 271 against Victoria and Ted McDonald, but like all the Englishmen he found it more difficult in the Tests, famous for being the first 5-0 outcome in Test history. The Englishmen were certainly outplayed, although they had their moments. For Patsy there was a half century in each of the first three Tests, and two thirties in the fourth, but he did not go past 67. He fielded brilliantly however, and made many friends.

As a batsman Patsy was a stroke player. Like many short men he was particularly strong square of the wicket, but he had all the shots and the basic foundation of a sound technique. He was particularly noted for being a fine player of fast bowling and a fearsome hooker of the short ball. That point is worth making at this stage because at first blush Patsy’s record suggests that he was one of those who was suffering from shell shock when McDonald and Jack Gregory squared up to England in the return series in 1921. That Patsy had the worst series of his career is clear, but his problem was being a nervous starter rather than a poor player of extreme pace.

In his initial encounter with the Australian fast bowlers Patsy scored 20 for Lionel Robinson’s XI in the first match of the tour. Three weeks later, for the MCC at Lord’s, he scored 40 and 52 as the Australians scraped home by three wickets. His place in the side for the first Test was assured, but Trent Bridge was a disaster for England and Patsy. Batting first Patsy came in at 18-2. The first delivery he faced from Gregory pitched outside off stump and went through to the wicketkeeper. The next looked the same, but cut in and sent his off stump cartwheeling. In the second innings he was digging in but was then responsible for Donald Knight being run out. Unsettled by that it was McDonald’s turn to get through his defences. He was bowled for seven.

Retained for the second Test at Lord’s Patsy found himself in in a crisis again, 24-2. As with Gregory at Trent Bridge thus it was with McDonald at Lord’s. This time the first two deliveries went past the off stump, and it was the third that came back in and hit the stumps. His confidence now in shreds Patsy struggled in the second innings, but at least saw the fast men off. By then he had got to ten, but he immediately relaxed and edged the leg spin of Mailey to Gregory at slip. England subsided to a second embarrassing defeat, and this time Patsy was dropped, not to return when, later in the series, the Australians lost their edge and England drew the fourth and fifth Tests without too much difficulty.

Despite his disappointments Patsy still managed his 2,000 runs for the season but, given one last tilt at the Australians he still couldn’t loosen the shackles. At the Scarborough Festival he was selected for C.I Thornton’s XI. There was no Gregory in the Australian line up, and no need for McDonald to bowl at Patsy as, this time, Mailey and ‘Stork’ Hendry dismissed him for 2 and 1.

In a career that was to go on for another 16 summers Patsy’s record is an impressive one. Twice, in 1922 and 1923, he topped the First Class averages and in the following five years was third, second, fourth, fourth and sixth. In 1928 and 1933 he exceeded 3,000 runs and there were only three seasons, two of them right at the end of his career in 1935 and 1937, when he failed to make 2,000, and even then he didn’t miss by much. Three times there were 13 centuries in a season

Having lost his England place in 1921 a return to Test cricket for Patsy came in 1924 when South Africa visited England. In unfamiliar conditions the South Africans looked like they might lose 5-0 until rain saved them in the last two Tests. Patsy played in all five matches, although he only got to the wicket four times. His lowest score was 50* and the higher of his two centuries 142. He was, inevitably after those performances, on the boat to Australia for a second time in 1924/25.

England were defeated again in Australia, but this time the fourth Test was won, and England were unlucky to lose the third match by just 11 runs. Such were the ravages of injury to their bowlers in that match that Patsy had to turn his arm over and, in having Mailey stumped by Herbert Strudwick, he took his only Test wicket. The last wicket had added 73. On both ESPNCricinfo and Cricketarchive Patsy is described simply as right arm slow. What led Mailey to his doom is not recorded, but such a pair of characters would doubtless have derived much amusement from the dismissal.

With the bat Patsy scored 314 runs at an average of just under 40 but the big score still eluded him with, as on his previous trip, three fifties but no century. According to former Australian skipper Monty Noble, the only man to fully chronicle the series in book form, Patsy batted pretty well, but was rather more defensive in the Tests than Noble had expected.

The elusive century against Australia finally came at Lord’s in 1926. It was a strange series for Patsy. There was that unbeaten 127 at Lord’s, but that apart he hardly got going, his other five innings bringing him just 59 runs. He still averaged 62 however, dismissed only three times. His contributions to the famous match at the Oval when Hobbs and Sutcliffe batted so brilliantly on a sticky wicket to claim the series were just 8 and 15. Noble was rather more impressed this time however, writing of the innings at Lord’s; When we were young we were taught that to retire in the direction of the square leg umpire for any reason was a crime. Hendren does it purposely in order to slash the short pitched straight ball through the covers – and how he slashed it!

A third trip to Australia came Patsy’s way in 1928/29. It was a great success for the team and Patsy himself had his most successful Ashes series. Percy Chapman’s men retained the Ashes with a 4-1 victory, and for Patsy there were 472 runs at 52.44. He began with 169 and 45 in England’s massive 675 run victory at the old Exhibition Ground in Brisbane, and whilst he did not match that again there were two more half centuries, including 95 in the final Test. There was some criticism however, Percy Fender, a teammate in 1920/21, writing; Hendren was patchy. Sometimes entirely brilliant, and then, not in the real mood, one would be left to wonder how he had ever managed to achieve some of the wonderful things he has done.

In 1929 Patsy was an automatic selection for the Test side against the visiting South Africans, but he had a disappointing series, and was dropped from the side for the fifth Test after passing fifty just once in the first four. He still made his two thousand runs however, and the summer did give rise to one of the enduring stories about him. The occasion was Surrey’s visit to Lord’s at the end of August, and the man who the tale belongs to is Surrey pace bowler Alf Gover.

Not having played at Lord’s before Gover arrived early, and found Patsy around the dressing room. They made their introductions and Patsy asked Gover what he did. On being told he was a fast bowler Patsy queried whether that meant really fast, going on to explain that he was getting older, and didn’t like the short stuff, and that he hoped Gover would bear that in mind whilst bowling at him.

Like any young pace bowler Gover was more interested in taking Patsy’s wicket than sparing his blushes, so the line of his attack when Patsy came into face him was obvious. There were three balls left in the over and Gover thought that was all he would need. He dug the first one in, and Patsy hooked the ball in the direction of Father Time and into the stand. Gover tried again, and second time round improved as he conceded only four. Third time lucky? No, a third bouncer went the same way as the first.

As Gover walked disconsolately away Hobbs went up to his young teammate and asked why he had just bowled three bouncers at Patsy. Gover explained that Patsy did not like fast bowling. Anyone familiar with Hobbs will be able to imagine the breadth of the smile on his face when Gover added that Patsy himself had been the source of this information, and the way Gover’s face dropped when Hobbs assured him that Patsy was one of the finest hookers in the game. Is the story true? It certainly should be, but in truth it seems unlikely – although the match was Gover’s first at Lord’s it was not the first time he had encountered Patsy. The pair had met at the Oval the previous season, and Patsy had taken a century from Surrey, so one suspects the story is apocryphal, unfortunately.

Despite his poor showing against South Africa Patsy was still invited to travel to the West Indies with England in early 1930, although that did not of itself suggest he was still considered an automatic choice for England. Another side went to play Tests in New Zealand at the same time (the only time this has ever happened), and the likes of Hobbs, Herbert Sutcliffe, Harold Larwood, Walter Hammond, and Maurice Tate remained at home anyway. England were unable to beat West Indies, winning one Test, losing one and drawing the other two, but Patsy had a magnificent tour averaging 135.76 in all matches, and 115.50 in the Tests.

Having already made the point that Patsy was a great favourite it is perhaps worth noting a couple of points in the debit column from that West Indies tour, if for no other reason than to show however much he might have been a crowd pleaser Patsy was also a tough competitor. The first came in a match against Trinidad when, with Patsy on 96, he was caught at second slip by Learie Constantine from the unorthodox left arm spin bowling of ‘Puss’ Achong. When Patsy had taken guard Constantine had been at first slip, and as he departed the crease he had plenty to say to Constantine about a move he clearly thought to be contrary to the spirit of the game. Next, a few weeks later in the third Test, Patsy and England were fighting hard to avoid defeat by batting out time and Patsy played his full part in trying to slow the game down. As the overs passed and the clouds gathered Patsy was ninth man out, lbw to a decision he clearly didn’t relish. Patsy took an inordinate amount of time to make his way back to the pavilion. The delaying tactics almost worked, but justice was done as the skies did not open until just after the last England wicket fell.

1930 was the year of Donald Bradman, and Australia regained the Ashes by a 2-1 margin. His runs in the Caribbean ensured Patsy started the series. He made an important 72 in England’s win in the first Test, and 48 in a losing cause in the second at Lord’s but, after Australia scored 729-6 change was in the air and Patsy was the batsman who made way for Maurice Leyland. Back in the ranks at Middlesex the runs continued to flow and Patsy did make the trip to South Africa that winter when, playing in all five Tests, he averaged 47.00 and, so it seemed, closed his Test career in some style.

In 1931 Patsy sustained, for the only time in his career, a serious injury. The match concerned was the Championship fixture at Lord’s between Middlesex and Nottinghamshire. Patsy, accompanied by his wife, bumped into Larwood as they entered the ground. Patsy and Larwood were of course old friends, and Mrs Hendren jokingly chided the Notts Express about not hitting Patsy. Larwood smiled and said he would ‘knock his block off’. Larwood did not normally bother to bounce Patsy, who he regarded as being as good a hooker of a cricket ball as he had seen. On this occasion he did however drop one short, Patsy went for the hook, made a rare misjudgement and was struck on the head. He went down like a light, his body twitching and terrifying all who were present. Patsy was rushed off to hospital, but fortunately was well enough a few hours later to reassure Larwood that he was not at fault. He still missed a couple of matches, a rare occurrence in those days.

Two years later, faced with the prospect of West Indians Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale bowling leg theory at Lord’s Patsy walked out to bat for Middlesex wearing a cap with not only a standard peak but what amounted to two more, protecting his temples, a piece of protective equipment designed and made by Mrs Hendren. The press and public did not approve. Patsy found the contraption too hot and did not make many runs, so the ensuing storm quickly died down. It is interesting to contrast the 1930s reaction with the safety first attitudes of the 21st century. It is notable that in a 1969 biography Ian Peebles, a former teammate who must have known the truth to be different, suggested that Patsy had never actually worn the three peaked cap in match conditions.

By the time Bradman returned to England in 1934 ‘Bodyline’ had come and gone and, at 45, Patsy was definitely a veteran. Early in the tour he was picked to represent MCC against the tourists, and scored a century. A fortnight later he scored a century against them for Middlesex and found himself back in the side for the first Test. He missed the fifth Test due to injury but retained his place throughout what was a difficult series for England. A confident 79 marked his entry back into the side in the first Test and he scored 132, his last Test century, and shared a partnership of 191 with Leyland in the third match.

Patsy’s reward for his efforts against Australia was another trip to the Caribbean, although he was nothing like as successful as on his previous visit. Four times he got to 38 in his eight visits to the crease, but in none of them did he go beyond 41. His best knock was probably the 20 he scored in the remarkable victory at Kensington Oval in the first Test (the story of which is told in this feature), but West Indies triumphed in the end, winning the series 2-1.

After returning from the Caribbean Patsy had a good summer in 1935 before in 1936, by now 47, he scored 2,654 runs, the fifth highest tally of his career. This was the season in which an 18 year old debutant made his 1,000 for the season and, in Denis Charles Scott Compton, Lord’s found a new hero. Patsy bowed out the following year, still not far short of 2,000 runs, but both Compton and Bill Edrich exceeded his tally, and he could retire safe in the knowledge that the county’s batting was in safe hands.

After retiring from Middlesex Patsy moved on to pastures new, as coach at Harrow School, a job he remained in until 1952. Then it was back to Lord’s for the 63 year old as he took the job of Middlesex scorer. It was congenial employment for a man who, if not wealthy, had enjoyed a comfortable living from the game. He had been granted two benefits in 1923 and 1931 as well as a testimonial in 1935. He remained in the scorebox until 1960 when, struggling with what would now be recognised as Alzheimers, he felt obliged to resign. Patsy Hendren was 73 when he died in 1962, a matter of weeks after the passing of brother Denis. Neither brother’s marriage had been blessed with children, so the line died with them.

Leave a comment