Born Before His Time

Martin Chandler |

The deeds of very few cricketers from before the Great War still resonate in the 21st century. The list might well be confined to Grace, Trumper, Ranji and Fry, batsmen all. The keener enthusiast will recognise a few more, bowlers such as Barnes, Spofforth and Lohmann. A man in a category of his own is Gilbert Jessop. The hardened cricket tragic apart the name means little, but is usually recognised, albeit with little insight as to why; “Yes, Jessop, I recognise the name, but I’m not sure why” being a far from unusual response.

Statistically Jessop has an impressive First Class record – a batting average of 35 and a bowling average of 22 confirm that, but at the highest level his 18 Tests brought modest rewards. He scored just 569 runs at 21.88, with one century and three fifties. With the ball he took a mere 10 Test wickets, at 35.40, and after taking the new ball on debut in his last seven Tests he bowled just two overs, so in the latter part of his career he was not really an all-rounder at all at the highest level. So why does his name still ring bells? It is a combination of two factors. First of all there is a Test match that has become synonymous with his name, “Jessop’s Match”, the final Test of the 1902 Ashes series. The other reason is that he has always been talked of as an “old-timer” who would have thrived in the one day game, whether 60, 55, 50, 40 or even 20 overs per side.

As a batsman Jessop was aggression personified. The state of the match, wicket or opposition bowling made no difference to the way he approached his task. He set the tone on his First Class debut and never looked back. His bow was in 1894 at Old Trafford. Lancashire had scored 351 after winning the toss and deciding to bat. The Gloucester reply was in tatters at 16-4, including WG for a duck, when Jessop came out to bat to face Arthur Mold, very fast and with a dubious action. Jessop’s first ball went for four, as did another before the over was finished.

From that game against Lancashire, which in the end was easily won by the home side, Jessop’s time at the top lasted twenty years, until the outbreak of the War in 1914 brought down the curtain on the career of the most exciting cricketer the game had seen. He was always an all-rounder but his role changed over the years. Initially he was mainly a bowler who tore up to the wicket and bowled as fast as he could. He wasn’t afraid to bounce batsmen either, causing some disquiet in one Varsity match for repeatedly bumping them down at the Oxford batsmen. As the express pace of youth faded Jessop did try and introduce some subtlety to his bowling, and latterly sometimes produced useful spells of off spin. It would be fair to say though that over the second half of his career he was only an occasional bowler, albeit one who still chipped in with a few wickets at reasonable cost.

Jessop was also a renowned fielder, displaying great pace in the outfield as well as a low, fast and accurate throw. He had a safe pair of hands as well, but it was his ability to run batsmen out that delighted the crowds. His speed and power saved many runs for his side, and of course his mere reputation frequently dissuaded batsmen from taking runs that, if truth be told, were there for the taking.

But it is as a batsman that the crowds flocked to see Jessop. In his early days he was thought of as a big hitter and little more, but such a description fails hopelessly to do justice to Jessop’s ability. Mere sloggers were men who occasionally came off at the end of an innings, not men who managed 53 career centuries, and he often went on further, the average of his three figure scores being as high as 140. But it was the rate of his scoring that was so eye-catching.

Unfortunately in Jessop’s day speed of scoring was measured in terms of time rather than balls received, so comparisons are not generally straightforward as over rates were much “better” in the “Golden Age” than they are now. It also needs to be borne in mind that until 1910, so the bulk of Jessop’s career, the ball had to be hit out of the ground rather than just over the boundary in order to score six. Despite that the figures remain remarkable. Taking his career as a whole Jessop’s runs came at a rate of 79 per hour, 83 looking at his centuries in isolation. In that currency some comparables are Len Hutton (36), Walter Hammond (43), Denis Compton (47), Ranji (50) and Vic Trumper (55).

In his entire career Jessop batted for more than three hours just once (he scored 240 in 200 minutes against Sussex in 1907 – none of his teammates scored more than 40). Jessop’s highest score, again Sussex suffered, was 286 scored out of 355 in two hours fifty minutes in 1904. In all a man who passed 50 on 179 occasions only spent more than two hours at the crease on ten occasions. His average time for a century was 72 minutes. Once, against Yorkshire in 1900, he scored a hundred in each innings, both of them before lunch. Yorkshire won the title that year, as they did eight times during Jessop’s career – he scored more runs and more centuries against them than he did against any other county.

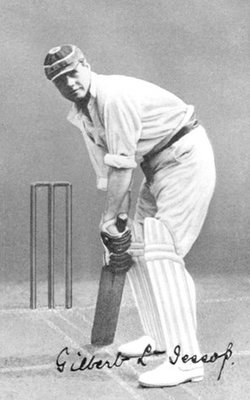

One irony of Jessop’s style of play is that he shaped at the crease as if anything other than the attacking batsman that he was. He was of moderate height, around 5 feet 7 inches, stocky, and always wore a cap whilst batting. His stance at the crease, with his legs well apart, earned him the nickname “The Croucher”. Unusually for his era he wielded a heavy bat, a long handle of course, and his hands were unusually widely spaced.

When the bowler delivered the ball Jessop was out of the traps like a startled greyhound, and he thought nothing of giving the charge to the quick bowlers, hoping that they would drop the ball short and allow him to unleash the cuts and pulls that his powerful wrists would send scorching to the boundary. The speed of Jessop’s foot movement, and the fact that he employed it against bowlers of all types, meant that for him there was no such thing as a good length ball that had to be defended. He could and usually would turn anything into a scoring opportunity.

Throughout his career Jessop played as an amateur, although there was no great private wealth. The second youngest of twelve children of a surgeon Jessop’s upbringing was however, by dint of his father’s professional status, comfortable enough until, at the early age of 53, the father died. Jessop was just 16 and the family’s much reduced circumstances obliged him to leave Cheltenham Grammar School. He became a schoolmaster, or more realistically a trainee schoolmaster, a route into the teaching profession that was taken by many in those days.

Always an impressive cricketer Jessop moved around various schools playing for a variety of teams but eventually was fortunate enough to be seen by WG, who was instrumental in his finding a place in the Gloucestershire side.

By 1896 Jessop, who at this stage considered himself to be primarily a bowler, had managed to get sufficient funds together to take up a place at Cambridge where he spent four summers. Jessop’s form improved with each passing year and in 1899 he scored almost 1,500 runs. Such was his progress that Jessop was picked for the second Test against Australia. His role was mainly that of strike bowler and he batted at number eight, but it was as a batsman that he was first called upon. England skipper Archie MacLaren won the toss and batted, only to see his immensely powerful batting side subside to 66-6, unable to cope with the blistering pace of Ernie Jones.

Jessop arrived at the crease at Lord’s for his first Test innings to join future skipper Stanley Jackson, the last recognised batsman. It was almost an immediate disaster as a bad call from Jessop left “Jacker” in no man’s land, and dependent on the usually reliable Syd Gregory fluffing his return in order to make his ground. After that the pair added 95 before Jessop, going for one more big hit, was caught in the deep by Trumper for 51. When his turn came to bowl his luck rather ran out as he slipped early on and strained his side. He bowled on though, and despite being in considerable pain ran in for more than 37 overs, taking a creditable 3-105. His figures would have been better still if three catches, including two from centurion Clem Hill, had not gone down. He contributed just four to England’s second innings, and was not called upon to bowl as Australia comfortably scored the 28 they needed for a ten wicket victory. He was not required for the rest of the series, replaced at Headingley by a young left arm medium pacer from Essex, “Sailor” Young, who took 12 wickets in his two Tests that summer and headed the England averages, but never played Test cricket again.

Despite his four years at the University Jessop did not manage to secure a degree, although whether the cause was lack of funds, insufficient time devoted to his studies or a combination of both is not entirely clear. It is probably as well for cricket that Jessop didn’t graduate though, as had he succeeded in doing so he may well have been lost to the game. His ambitions lay with the Church, but for that calling a degree was a pre-requisite.

As the new century dawned Jessop became a member of the stock exchange. Two years later when he married he gave his occupation as ‘stockbroker’, although there is little evidence that he was particularly successful in that occupation, nor indeed that he devoted very much time to it. In 1900 the die was cast for the rest of his cricket career. WG had left Gloucestershire to pursue his London County venture and Jessop, not yet 26, inherited the county captaincy, which he was to retain for a dozen years. It had no effect on his form as he enjoyed the best season of his career. For the second and final time he took a hundred wickets for the season, and with more than 2,000 runs to go with them he became one of the few who have completed that impressive double.

In the winter of 1901/02 Jessop toured Australia with MacLaren’s side. He played in all five Tests but met with little success in any of them, or indeed on the tour as whole. He had toured North America twice in the past, and this was to be his final overseas trip. He suffered very badly from seasickness which, in those days of long voyages by sea must have been a disincentive and his marriage, to a passenger he met on board during the return from Australia, put an end to any remaining ambitions to travel.

Despite his failings in Australia there was never any real question but that Jessop would be selected for the 1902 Ashes series and he was one of the squad of 14 selected for the first Test and asked to play. He contributed just 6 to England’s 376, and unsurprisingly didn’t get the chance to bowl as George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes shot Australia out for 36 as time ebbed away on the final day. The rain ruined the second Test as well, and Jessop didn’t even got onto the field in the couple of hours play possible on the first day. In the third Test, from number nine, Jessop scored just 12 in the first innings and barely bowled at all. MacLaren asked him to go in first in the second innings and he scored a rapid 55. It was to no avail however as England lost by 143, and despite MacLaren’s faith in him Jessop was left out for the fourth Test. There can be little doubt the result of that famous game, which Australia won by three runs, would have been different had Jessop and not the unfortunate Fred Tate been selected.

There was just pride to play for when the two teams arrived at the Oval for the fifth Test, and for England Jessop was back. Australia won the toss and their first innings of 324 looked a long way distant when England were caught on a wet pitch on which it was all they could do to avoid the follow on. Jessop contributed 13 in eight minutes. The situation looked bleak for England, but the demons in the pitch were still there, and after Trumper paid insufficient respect to the Jessop arm the visitors ended the second day on 114-8, just 255 ahead. Had it not have rained again England might have had a decent chance, but the heavens opened again and saturated the uncovered wicket overnight. The writing was on the wall as the last two Australian wickets mustered just seven more runs, to set England a distant 263 for victory.

England’s start was disastrous, as they slipped to 10-3. As if to mock them the rain then returned for a short while, just to keep the odds stacked high in Australia’s favour. When the skies cleared it soon became 48-5, at which point Jessop, career average against Australia 20.46, strode out to join Jackson. He looked like a man in a hurry, and he was. Runs came from each of the first six deliveries that he faced. There was just one concession to the opposition and the conditions, and that was the direction in which Jessop looked for runs. Hugh Trumble could turn the ball a lot, and at the other end the batsman barely got a sight of Jack Saunders as he began his run behind the umpire before appearing just in time for his delivery stride. The big cross-batted hits to leg were eschewed, and Jessop kept his bat much straighter than usual and the sanctuary of lunch was reached at 89-5 – Jessop had been responsible for all but 12 of the partnership.

The pitch was a little easier after lunch and Jessop was able to play his natural game against Saunders, who visibly wilted under the pressure. At one point a cut from Jessop’s bat from him led to an all run five, the vastness of the Oval playing area being another factor that made the speed of Jessop’s assault remarkable. Eventually Saunders was rested, but by then Jessop was able to tuck into Trumble as well, and Warwick Armstrong’s slow medium leg breaks held no terrors for “The Croucher”. After just 75 minutes at the crease it was a boundary from the not then so “Big Ship” that brought up the century. It was by far the fastest Ashes hundred ever scored and remained so until Adam Gilchrist’s pyrotechnics at Perth in 2006/07 – a fine innings but one compiled in benign conditions in a wholly different match situation.

It seemed for a time that there might be a tame end. After one more boundary from Armstrong Jessop seemed, for once, to be caught in two minds. He should have perished, if he was going to be dismissed at all, to a superb running catch in the deep field whilst looking to clear the rope once again. As it was he tamely lobbed an Armstrong delivery into the delighted hands of Monty Noble at square leg. Most on the ground expected that to be the end, but one hopes that no one left, because a fine innings from Hirst and his famous partnership with Rhodes meant that Jessop’s effort had not been in vain. England crept home amidst growing tension by one wicket. I would think that Bob Willis well knows how Hirst felt. The Yorkshireman, whose overall Test record, like Jessop’s, does not do justice to his career as a whole, took five wickets in Australia’s first innings, and scored a crucial 43 in England’s grim reply as well the unbeaten 58 that took them to victory. Yet in the same way that Headingley ’81 will always be “Botham’s Match”, so was the Oval ’02 destined to be known as “Jessop’s Match”.

After their triumph at the Oval England did not have another home series until the 1905 Ashes, and with memories long the selection of Jessop for the first Test, despite his form for Gloucestershire being no more than ordinary, was a popular one. Sadly he was out without scoring and played no further part in the series. His county form picked up a little as the season progressed, but when he failed to record even a single century in 1906 it seemed like he may have lost what he once had. Some suggested that by concentrating too much on the game of golf Jessop’s cricket was adversely affected. If it did the reverse wasn’t true, as he eventually played golf off scratch.

Fortunately 1907 proved that Jessop had not lost his form completely and he returned to England’s colours for the first Tests played in England by South Africa. His form in the Tests was patchy, but there was one innings that saw him at his best. In the first Test he scored 93 in just 75 minutes as England took a 1-0 lead in the series. The quartet of South African googly bowlers eventually levelled the series and Jessop seemed as fallible against them as any of his teammates, but he had shown in scoring that 93 that the mystery bowlers could be dealt with.

For the next four summers Jessop batted as well as ever, and in 1911 he scored more than 1,900 runs at 42 with as many as seven centuries, but for all the thrills that the followers of the County Championship had Test match audiences were disappointed. Jessop was called up for the first Test in 1909, and scored 22 in a low scoring encounter, but then in the third Test he had a nightmare. He pulled muscles in his back after an hours play whilst attempting a swift pick up and return. The doctor in the dressing room wrongly diagnosed a slipped disc, and the incorrect treatment that he then administered left a legacy for the rest of Jessop’s life, and ended his season.

There were though still two more Tests to come for Jessop, as he was called up for two of the three Tests against the weak South African side who competed in the 1912 Triangular tournament. He achieved little however, and gave up the Gloucestershire captaincy for the 1913 season. He enjoyed some success that year, comfortably making his 1,000 runs for the fourteenth and last time. His career drew to a close in 1914, a summer in which he celebrated his fortieth birthday. His final match was against Somerset. In the first innings he top scored with 25 in 18 minutes, and in the second hit his first ball to the boundary before being stumped off the third. His bowling was a rarity by then but he took 4-34 and 1-7 and held a couple of catches as Gloucestershire won a very low scoring game by one wicket. As so often in the past Jessop’s contributions had changed the course of a match, and in that sense it was a fitting end to a wonderful career.

When EM Grace retired in 1909 Jessop was appointed secretary at Gloucestershire, no doubt a welcome source of additional income. As well as the generous expenses he was paid as captain Jessop had also been writing regularly for the Daily Mail since 1903, so it is difficult to imagine he had much time for stockbroking. But with the outbreak of war Gloucestershire closed down, and with cricket doing likewise there was little to write about. So Jessop joined up and took a commission as a Captain in the 14th Manchester Regiment. He spent the early part of the war recruiting with MacLaren, and played a good deal of cricket, when his old back injury permitted.

In 1916 Jessop was plagued by lumbago, so a radiant heat treatment was arranged. This involved the patient getting into a contraption that resembled an iron lung, with the body then subjected to jets of steam. The prescribed time was 30 minutes, but the patient could extract himself from his situation at any time. At least he was meant to be able to, but the catch was accidentally left down for Jessop and, as the attendant disappeared, he was in trouble. When finally released he had sustained damage to his heart. Jessop never played cricket again and was invalided out of the army. His sporting career was over, and the extent of his disability can be measured by the fact that when in the 1920s the BBC were looking for a commentator when they began broadcasting Test cricket Jessop had to decline the offer he received, as he couldn’t guarantee to be fit to work on any given day. Despite the problems his heart gave him Jessop lived on until he was almost 81. For many years prior to his death he had lived with his son Gilbert, a vicar who, when his calling permitted, was himself a fine attacking batsman and off spinner at Minor County level.

There have been many who have made the obvious observation about the place Jessop might have found in the modern game, but the best known is Richie Benaud, as astute a cricket man as I have heard, who describes him as perhaps the best one-day player to have ever lived and never played that form of cricket. Gilbert Jessop was a genuinely quick and hostile bowler, a fearless hitter of a cricket ball and a magnificent ground fielder – the IPL would have loved him.

Leave a comment