The Bard of Basingstoke

Martin Chandler |

Back in 1969 The Noble Game of Cricket*, a large coffee table type book, was published. It is a showcase of sixty examples of cricketing art, so not of immensely wide appeal although there was sufficient interest in it to persuade the publishers to produce a second edition in 1986. For many the book was notable as much as anything because it was jointly written by, with all due respect to EW ‘Jim’ Swanton, the two leading cricket writers of the day, Neville Cardus and John Arlott.

The famous pair had not worked together before, nor were they to do so again but they seem to have enjoyed a good relationship. Arlott described Cardus as a friend, although the pair seem not to have been particularly close. The Noble Game of Cricket consisted of an introduction by Cardus, in his usual style, followed by reproductions of the chosen works, each summarised briefly by Arlott.

I have not been able to discover how the project came about, but it is unlikely that the entirely separate roles of the two men called for a great deal of collaboration. There is perhaps a clue in one of the few comments I have been able to find from Cardus about Arlott. A year before the book was published Arlott had been appointed the cricket correspondent of The Guardian, the position which had given Cardus his opening almost half a century before. Cardus’ quoted reaction was I have always admired Arlott’s economy of words, his ability to depict a scene or character as though by flashlight …….. he is one of our most civilised writers. That economy of words is well illustrated by, for example, Arlott’s verdict on the great Barry Richards; He butchers bowling, hitting with a savage power the more impressive for being veiled by the certainty of his timing.

Arlott was born in 1914 in Basingstoke and was therefore a quarter of a century younger than Cardus. The two men did not therefore have a great deal in common outside cricket, albeit for neither was cricket the be all and end all, something which doubtless contributed to the quality of their writing. In addition neither went straight into the press box, and neither was a good cricketer. Cardus was a noted music critic in addition to his cricketing duties. Arnott was a poet, wine expert and, of course, an accomplished broadcaster.

After leaving school Arlott worked in his local town hall briefly before spending four years as a records clerk in a mental hospital. He then joined the Southampton Borough Police, a job he stayed in for a dozen years, rising to the rank of Sergeant. He spent much of his free time in the summer watching Hampshire play cricket, and another abiding passion was writing poetry.

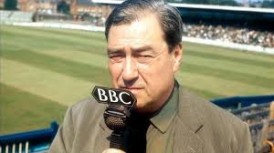

Eventually Arlott’s poems brought him to the attention of future Poet Laureate John Betjeman and, through him, to the BBC and in 1946, after spending some time combining his police duties with BBC work Arlott joined the corporation as an Overseas Literary Producer. When, that summer, the management were looking for someone to broadcast to India on the 1946 tour Arlott was given the task. The rest, as they say, is history.

The first cricket book to appear from Arlott’s pen came the following year, Indian Summer being an account of that first post war series. There were then four more similar accounts. Gone to the Cricket in 1948 dealt with the 1947 South Africans, and Gone to the Test Match recorded the ‘Invincibles’ visit of 1948. Gone with the Cricketers chronicled Arlott’s first overseas trip with the 1948/49 tour of South Africa and the visit to England the following summer of Walter Hadlee’s New Zealanders. Arlott had strong liberal values and found apartheid abhorrent. He never visited South Africa again after 1949 and later played a major role in Basil D’Oliveira’s migration to England. The fourth in this series of books, Days at the Cricket, concerned the visit of the 1950 West Indians.

There were other books from Arlott at this time. Passionate about the history of the game he was involved in the repackaging with new introductions of two books of reprints of rare and almost unobtainable nineteenth century books. In 1948 From Hambledon to Lord’s: The Classics of Cricket appeared, to be followed a year later by The Middle Ages of Cricket. The first included the work of John Nyren, Charles Cowden Clarke, James Pycroft and John Mitford. The latter was Pycroft again, and also reproduced William Denison’s collection of pen portraits from a century before, The Sketches of the Players.

Also in 1949, in the manner of Cardus, Arlott gathered together a selection of his own essays that had appeared elsewhere, Concerning Cricket. A very similar collection, The Echoing Green, appeared in 1952. The former is a fine book, the latter quite outstanding. Arlott also found the time to publish How to Watch Cricket in 1948, to edit a selection of the work of others on the subject of the First Class counties, Cricket in the Counties, in 1950, and to work with Stanley Brogden on a second edition of Brogden’s classic account of The First Test Match: England v Australia 1877.

There were three biographies from Arlott over the course of his life. The first was a slim book about Maurice Tate that appeared in 1951. More substantial efforts in respect of Fred Trueman (Fred: Portrait of a Fast Bowler) and Jack Hobbs (Jack Hobbs: Profile of The Master) appeared in 1971 and 1981.

In Coronation year Arlott wrote Test Match Diary 1953 on the subject of that summer’s Ashes series. He also edited Cricket, a book in the Pleasures of Life series, which contained a number of his own essays as well as the work of others. His next book was his second and last account of an overseas Test series, Australian Test Journal, one of the many accounts of Len Hutton’s men’s 1954/55 Ashes triumph.

It would then be 1959 before Arlott published his Cricket Journal, which was in large part an account of the very unsuccessful visit to England that the New Zealanders endured the previous summer. In the next three seasons England’s visitors were India, South Africa and Australia and Cricket Journals 2, 3 and 4 recorded those series. With the genre gradually becoming less attractive there was, a decade later, to be just one more tour account from Arlott, The Ashes 1972.

In the latter part of the 1950s there were three other Arlott books. First, The Picture of Cricket, a modest 32 pages, appeared in 1955 and, as the title suggests, deals with cricket illustrations. That was followed in 1957 by Alletson’s Innings, a 40 page account of the remarkable 189 that Ted Alletson scored for Nottinghamshire against Sussex in 1911. Finally, and also in 1957, Arlott contributed 59 pages to the official history of the Hampshire county club.

It was then to be 1967 before Arlott published Vintage Summer, a look back at the remarkable English season of 1947 when Denis Compton and Bill Edrich carried all before them. After that there came the Trueman and Hobbs books already noted, and the 1972 Ashes book, but a number of collections of essays apart that was to be the end of Arlott’s cricket output until, finally, an autobiography appeared in 1990, the year before he died. Arlott perhaps left the project too late as Basingstoke Boy is a little disappointing. For those wanting to know more about Arlott David Rayvern Allen’s 1994 authorised biography**, Arlott, is a better read, and more so is Stephen Fay and David Kynaston’s Arlott, Swanton and the Soul of English Cricket.

None of Arlott’s books are rare in themselves. Two appeared in limited editions as well as standard books, there being 200 signed and numbered copies of Alletson’s Innings and 200 of Basingstoke Boy, again signed and numbered and also leather-bound. Shortly before Arlott’s death book dealer John McKenzie published an expanded edition of Alletson’s Innings, again in a signed and numbered limited edition. For those familiar with the Arlott signature the clearly frail scrawl is a sad sight, especially as just a few weeks before that, when signing copies of the limited edition of his poem Harold Gimblett’s Hundred, which Richard Walsh published, the Arlott hand had seemed as firm as ever.

Arlott remains popular with collectors in part because of his habit of off printing essays from his books and issuing them in small signed and numbered limited editions. The Old Man, an essay on WG Grace from Concerning Cricket was thus released in a limited edition of 12. There are 10 copies of Athol Rowan from The Echoing Green, and a mere three of The Works of JC Clay from Cricket, and half a dozen of Jim Laker, which came from a 1969 collection of essays; Cricket: The Great Bowlers. Another was Jack Hobbs; An Appreciation which was off printed from John Arlott’s Book of Cricketers. There are twenty copies of that one and fifteen of The Boy Collins, an essay on AEJ Collins (he of the 628* in a Clifton College house match in 1899) that, as far as I am aware, was the only one of these that was an original work and not an offprint.

Although many of Arlott’s books concerned Test series he was a great lover of county cricket. Unlike some other writers he was also a great admirer of the players, and spent many hours in dressing rooms getting to know the men whose play he so admired. In his own words; The heart of English cricket is the county game; and the essence of county cricket is not the Test star who dominates it, but the ordinary county cricketer who is there every day and gives it his constant and fullest effort.

Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s a number of Hampshire beneficiaries had cause to be thankful to Arlott as he produced short biographical sketches of them, had a few copies signed, numbered and specially bound for sale with the proceeds going to the benefit. Needless to say the items in question are now highly collectable. The fortunate beneficiaries were Neville Rogers (1956 – 12 copies), Leo Harrison (1957 – 70 copies), Derek Shackleton (1958 – 50 copies), Vic Cannings (1958 – 50 copies), Jimmy Gray (1959 – 50 copies), Roy Marshall (1961 – 50 copies), Arthur Holt (1963 – 50 copies), Mervyn Burden (1964 – 25 copies), Henry Horton (1964 – 50 copies), Peter Sainsbury (1965 – 50 copies) and finally David ‘Butch’ White (1969 – 25 copies). Very similar in format are appreciations of two amateurs, Desmond Eagar (1958 – 20 copies) and Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie (1962 – 50 copies).

For the Arlott collector there are three other items worth mentioning, two produced for cricketers’ benefits and the last a posthumous publication by Richard Walsh Books being a limited edition of 50 copies of an essay on Wilf Wooller which had been written twenty years earlier for the Glamorgan handbook. The benefit publications were not like the others referenced in that they were neither signed, numbered nor cloth bound, but nonetheless the appreciations of Gloucestershire’s Sam Cook and Hampshire’s Danny Livingstone that appeared in 1957 and 1972 respectively are both rare and sought after.

To return, briefly, to The Noble Game of Cricket, history seems to be treating Cardus and Arlott rather differently. As those who recall him depart this mortal coil Arlott seems to be sliding quietly into history. Cardus on the other hand still creates interest and his legacy is debated to this day with new publications appearing regularly including a major new biography and separate anthology recently released. The styles of Cardus and Arlott may be very different, but both are as readable now as they were in their heydays.

In addition to the books mentioned the name Arlott appears on the spines of a number of other books most of which are either anthologies of Arlott’s own works or collections of the work of Arlott and others that Arlott edited. Foremost amongst the anthologies are Arlott on Cricket, A Word from Arlott and Another Word from Arlott, all of which were edited by Rayvern Allen. Examples of the latter are Cricket: The Great Ones, John Arlott’s Book of Cricketers, Cricket: The Great Bowlers and Cricket: The Great All-Rounders. There is also another biography of Arlott, a very personal book written by his son Tim.

*The first edition of The Noble Game of Cricket appeared in a standard hardback and also a numbered limited edition signed by both authors and used in a slip case.

**Rayvern Allen’s book also appeared in a signed, numbered and specially bound limited edition which, there being a mere dozen copies, is very rarely seen.

Leave a comment