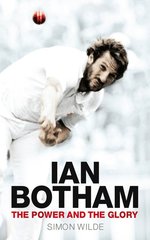

Ian Botham: The Power and the Glory

Martin Chandler |Published: 2011

Pages: 384

Author: Wilde, Simon

Publisher: Simon and Schuster

Rating: 4 stars

It is almost twenty years since Ian Botham last played First Class cricket but, the claims of Andrew Flintoff and Kevin Pietersen notwithstanding, few would dispute that he remains the biggest name in English cricket, with no reason to believe that that status is going to change any time soon.

It is not difficult to explain why this is the case. For an all too brief period as the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, Botham was the greatest all-round cricketer to have graced the game. The 1981 Ashes series defines him, his unforgettable contributions at Headingley and Old Trafford with the bat, and Edgbaston with the ball, being amongst the best known cricketing performances ever produced. There were however many other displays that deserve as much credit, if not more for their technical quality. The outstanding all round contribution to a ten wicket victory in the Golden Jubilee Test in India in February 1980 (114 in his only innings coupled with 6 for 58 and 7 for 48), and his remarkable batting throughout 1985 being just two of them. The key to his batting was a wonderful eye coupled with a sound technique and an unwavering belief in his own ability. As to his bowling the reason for Botham’s success is readily apparent from the image on the dust jacket of Ian Botham: The Power and the Glory – just look at the position of that seam.

Amongst the thrills there were of course some spills as well. Botham’s short and difficult time as England captain, and the relative weakness of his record against West Indies are the two most frequently cited, although for me the way his career entered a terminal decline at a time when I believed he should still have had much to offer the game, particularly as a batsman, was the most frustrating.

But the size of Botham’s footprint in the public conscience was not solely as a result of what he did on the field. He attracted almost as much publicity from an allegation of assault that was fought out before a Magistrates Court, an allegation of drug taking that was dealt with by the game’s moral guardians, as well as an affair and the consequent matrimonial difficulties that were picked over ad nauseam by the tabloid press.

What is, in the circumstances, surprising is that Botham has had things his own way for so long in the life story stakes. There have been biographies before, mainly exercises in hero-worship if I recall correctly, but I do not believe there has been anything subsequent to 1994’s My Autobiography and 2010’s Head On to provide an impartial account of the great man’s life.

It was therefore with great anticipation that I opened Simon Wilde’s biography of the man who bestrode English cricket like a Colussus in my youth. Wilde is an excellent journalist, already responsible for fine biographies of Shane Warne and, to show his versatility, Ranji. I was not disappointed. This book is at least the equal of the other two.

Inevitably all the well-known stories are dealt with, almost always by reference to what others who were present have told Wilde, and the manner in which he has allowed Botham’s life story to tell itself through those recollections serves him well. It was pleasing to see that in the past Botham has clearly been honest when recounting the tales himself. Naturally there are some instances where he has, perhaps understandably, been unable to be entirely objective, but if anyone is looking in this book for a “smoking gun” they are going to be disappointed.

What I was most interested in was learning more about Botham the man and here Wilde certainly did not let me down. I remember an evening in the early 1990s when I attended a benefit function where Botham was a guest speaker. A good friend of mine, who had never met Botham before, had been at University with the beneficiary was on the “top table” at the informal function that was held in a pub in the Home Counties. Botham held court splendidly, but when introduced to my friend looked at him and through him, and throughout the evening on those rare occasions when he was not speaking gazed intently at him, frowning, with an expression on his face that clearly said “Who the **** are you and why are you here?”

The best man to help to explain Botham the man must surely be Mike Brearley, and his views are certainly here, and there are many other interviews that shed light on that question. Wilde fully explores what he describes as “Brand Botham” and the efforts that Botham made to maximise his income during his career. Botham was of course knighted for his charitable work, and those famous walks he undertook, although Wilde suggests that exposure of the brand was if not an equal motivation to the benefit to the charities concerned, then certainly a significant one. Similarly he explores the issue of whether the reason Botham declined the opportunity to take the Rebel’s Rand for touring South Africa was really so he could “continue to look Viv in the eye” or more because on a full analysis the devaluing of the brand was too great a price to pay for whatever the South Africans were offering.

The measure of Wilde’s success is that when I finished the book I knew a lot more about what makes Ian Botham tick than I did before I picked it up and, perhaps more importantly, next time I see my old friend, and assuming he hasn’t read Ian Botham: The Power and the Glory I can explain to him just why he was treated in the way that he was on that February evening two decades ago.

Leave a comment