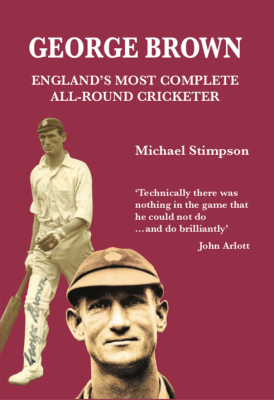

George Brown

Martin Chandler |Published: 2018

Pages: 187

Author: Stimpson, Michael

Publisher: Dorch Publications

Rating: 3.5 stars

The sub-title of Michael Stimpson’s biography of George Brown is England’s most complete all-round cricketer. The coupling of that on the front cover with the late John Arlott’s observation that, technically there was nothing in the game he could not do …… and do brilliantly, suggests the book might be an unrealistic hagiography. I will therefore say at the outset that that is not the case, and that George Brown is recommended reading.

Although, as Stimpson concedes, Brown’s name is almost never mentioned today that was not always the case. The book is littered with quotes from Arlott, clearly a great admirer of Brown, and who was certainly responsible for my knowing a little about a man who he was always likely to wax lyrical about given half a chance. Arlott’s departure from the BBC commentary box in 1981 brought all that to an end however, and no one who is under 45 years of age, save for hardened cricket tragics, will know anything of Brown, or what Stimpson means by his sub-title.

I suspect that author Stimpson is one of those under 45s, as he tells the story at the start of his book as to what the catalyst for it was. He explains that whilst thumbing through a collection of Arlott pen portraits in a charity shop he spotted Brown’s name in the list of subjects and, intrigued by the appearance of a name he had not heard of it, bought the book in order to read the Brown essay. He goes on to express the view, and with this I would respectfully disagree, that this biography should have been written by Arlott. I think Arlott would have disagreed too. He had every opportunity to write a biography of one of his Hampshire favourites, but never took it. He has written short pen portraits of them all, pieces without exception full of warmth and affection – Arlott was a man whose objectivity could be compromised, and I suspect he knew that as well as anyone.

Inevitably Stimpson has been influenced by Arlott, but what he hasn’t done is take everything that Arlott writes at face value and hasn’t been afraid to examine some of the stories that he picked up during his extensive research and question what has been written elsewhere. I should also stress at an early stage that what he does not do, despite that sub-title, is try and suggest that Brown was a great all-rounder. His use of the word complete is deliberate and entirely appropriate. As a young cricketer Brown was a batsman/wicketkeeper. He then became a professional so started to bowl fast in an early club engagement and enjoyed considerable success. As a result you have a man who scored more than 25,000 First Class runs and took more than 600 wickets. Briefly, between 1921 and 1923, he was an international player and capped seven times by England. On each occasion he was selected to keep wicket and never bowled a single delivery in a Test match.

As far as the brevity of his Test career was concerned Brown was one of those called up to face the music of Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald in 1921. His turn came after two defeats and he played in the rest of the series. With scores of 57, 46, 31, 32 and 84 and some competent displays behind the stumps he certainly made his mark. A long run in the side beckoned, but in fact Brown’s only other Tests came in South Africa in 1922/23, where 49 runs at 9.80 tell their own story. He wasn’t invited to play for England again, although at county level he remained a fine player and consistent performer. The highlight of his career came whilst an England player, in 1922, and was the 172 he scored against Warwickshire to lead Hampshire to victory after they had been all out for 15 in their first innings.

The volume of available material from newspapers is such that Stimpson would not have had any difficulty in putting together a biography from that source alone. and indeed I was a little concerned that that might prove to be the case. Fortunately it wasn’t, the main reason being the help and co-operation that Stimpson received from two of Brown’s grandchildren and, a great grandchild who is the family historian. Their assistance, coupled with Arlott’s writings, enable Stimpson to get behind the cricketing achievements and portray a rounded picture of Brown the man.

As far as Brown’s story is concerned he started his working life as an attendant in a mental hospital near Oxford, an occupation which cannot have been easy. Legend has it, and the man himself never denied this, that Brown walked all of the sixty plus miles between his home and Southampton for a trial with the county. With all his kit with him that would have been at least three days of walking. How was the introduction made and how confident of success was he are two associated questions. Stimpson is clearly a little sceptical, and examines the episode with the help of contemporary documents and family stories. The romance of the walk clearly appealed to Arlott, and it is doubtful he would ever have questioned it.

It is unlikely too that Arlott would have dealt with Brown’s contribution to the Great War at any greater length than he did that of Jack Hobbs in his biography of The Master, published in 1981. Hobbs was in a tricky position, married with young children, and he has been the subject of some criticism, particularly as so many talented sportsmen did volunteer for service straight away. Brown too did not volunteer, although conscription eventually extended to him in 1917, but even then he did not see active service. As can be imagined this was a big issue in the aftermath of such a brutal conflict and there is some suggestion that Brown’s omission from the 1920/21 Ashes party, after a fine season, was a reflection of his having an ‘easy’ war. It is not a subject that Stimpson shirks from, and whilst definitive conclusions are impossible at this distance in time it is one of the most interesting parts of the book, particularly as on the cricket field Brown’s bravery was legendary. He was always happy to face the fastest bowling, and although Stimpson has a few sensible observations on the subject, was by reputation far from averse to adopting the Brian Close approach to fast and furious bowling and standing up straight and allowing the ball to cannon into his upper body.

The fact that his grandchildren have memories of Brown from his later years bring interest and depth to the story of the post playing career of a man who kept out of the limelight after retirement. In particular the account of Brown’s job as a parking attendant in Winchester in his late sixties is an eye opener. The book is rounded off by a verbatim account of the emotional eulogy that Arlott gave at Brown’s funeral following his departing this mortal coil in December 1964, followed by an equally affectionate if rather more objective conclusion from Stimpson.

There are a few statistics at the end of the book, but sadly no season by season record of Brown’s doings on the field, which would have been useful for those without a Cricketarchive subscription. There is also no index, but on the other hand sources are well referenced and there are some excellent photographs. The book was also free of factual errors, recovering from a slightly worrying start in which Warwick Armstrong being bracketed with Gregory and McDonald as a very good seam bowler raised my eyebrows.

Leave a comment