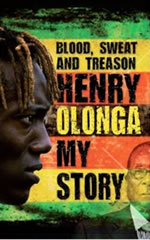

Blood, Sweat and Treason

Martin Chandler |Published: 2010

Pages: 275

Author: Olonga, Henry

Publisher: Vision Sports Publishing

Rating: 4.5 stars

Zimbabwe cricket has had a chequered existence since acquiring Test status in 1992. The earliest Test sides were comprised solely of white players until, in 1995, Henry Olonga became the first black African to gain selection. Between then and 2003, when the famous protest of himself and Andy Flower cost him his place and any prospect of a safe existence in Zimbabwe while Robert Mugabe ruled, he played 30 Test matches and 50 ODI’s over a period in which the fledgling Test nation fully justified their elevation to the game’s top table.

In years to come, when the political landscape in the country is different, someone will no doubt write a definitive history of Zimbabwean cricket. In the meantime Olonga’s autobiography is the first published by a Zimbabwean Test player. It is not, and was never going to be, a standard season by season analysis of a cricketer’s career. In fact this book could have been many things. Olonga might, though I am pleased he did not, have used his book as a platform from which to make an overtly political statement. He might also have tweaked his story with a view to then garnering further commercial opportunities from a dramatisation of his life. A bit of exaggeration here, a few events taken out of context there, and he would have had a plot that would not disgrace a Jeffrey Archer novel. It is therefore to his eternal credit that all his book seeks to do is tell the story of his life to date and it is no surprise, given all that has happened to him in his 34 years, that the result is one of the most compelling stories I have ever read, and one that is certainly quite unlike any other cricketer’s autobiography.

Even amongst those who have not led the sort of life Henry Olonga has a glittering playing career is by no means a prerequisite for an interesting autobiography. As a cricketer Olonga was by no means an all time great and outstanding performances from him were the exception rather than the rule. That said I had not realised his bowling was as sharp as it clearly could be (I managed to find some footage on youtube), nor that his career was dogged by injury to the extent that it was. I was left wondering just how different his purely cricketing legacy might have been had he remained injury free and had access to the sort of top quality coaches who would have made sure he did not, at the age of 19, have to remodel his action after it became the subject of criticism in his early internationals. The story of his career is eloquently and modestly told and would have been of particular interest simply by virtue of being the first time the cricketing upbringing of a Zimbabwe player has been dealt with in such a way.

There is though, of course, much else besides cricket in this book and many will read it primarily for the insights it gives into life in Zimbabwe. This is where the narrative is at its best as Olonga thoughtfully and concisely gives his reader just enough information about the nation’s history and politics to enable his story to be fully understood. He also recounts, with the skill of a seasoned storyteller, the events of the three occasions when he had to face up to the possibility of his imminent demise. The first time was on tour in Sri Lanka when only the intervention of his captain, Alistair Campbell, and a lifeguard, prevented him from drowning after an ocean current took him away from the rest of the team. Later on, back in Zimbabwe, he was the victim of a brutal car jacking and robbery and was then driven around for some time by the perpetrators, wholly unsure as to what their intentions towards him were. For the vast majority of us either one of those two experiences of our lives flashing before our eyes would have been more than enough, but Olonga had the courage to make the decision to take his life in his hands again in the black armband protest at the 2003 World Cup.

This story has a beginning and a middle. It does not yet have an end, nor even the beginning of an end. Henry Olonga is currently living in London with his Australian wife, Tara. Since 2003 he has worked in broadcasting and, blessed with a fine singing voice to go with his love of music, he has released an album. Whether, in the short term, he will remain in the UK or go to Australia is the first question that is left open. I suppose the second must be whether, once Robert Mugabe is dead, deposed or otherwise no longer a threat to him, he will return to Zimbabwe. I have to say that reading his book conjures up, for me at least, an image of Henry Olonga being an apolitical but unifying figure in his country, respected by all and capable of helping to lead the nation back to normality. Whether Henry Olonga might share that vision, or any part of it, is not answered here but time will tell and, whatever he does with his future, I wish him the very best.

Leave a comment