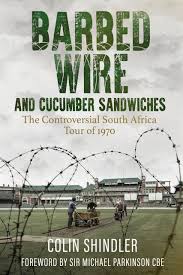

Barbed Wire and Cucumber Sandwiches

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 320

Author: Shindler, Colin

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 4.5 stars

And now we have two, as the second of the three promised books on the cancellation of the 1970 South African tour has arrived. I will say at the outset that Barbed Wire and Cucumber Sandwiches is rather different in approach from Tour de Farce, thus for those interested in learning more about this historic episode the books are complementary, and not alternatives.

There is a significant message at the very start of chapter one; It is impossible to understand the passion that consumed both sides in the first six months of 1970 until the events of 1968 have been appreciated. I was eight years old at the time – some of the stories highlighted in the helpful timeline are ones I was just about conscious of – the Vietnam war, the Prague Spring and the assassination of Martin Luther King, all of which I learned much more about as I got older. The ‘D’Oliveira Affair’, as it was cricket, I knew a little about at the time but the story I recognise, but have to confess to never having subsequently looked into, was the student unrest in Europe and, in particular, France.

I would say straight away therefore that I am grateful to Colin Shindler for two things in particular, firstly his enlightening me as to what was going on on those French campuses, and secondly for pointing out something I had never really fully taken on board before, that being that there was a much wider context to the campaign to stop the tour than I had previously realised.

Having set the scene Shindler continues his story with a look at the almost completely forgotten but far from uneventful 1968/69 MCC trip to Pakistan before running through the events of the 1969 summer and then, following that in the close season before the South African cricketers were due to arrive, the experience of their Rugby Union playing compatriots.

Much as I had previously taken an interest in the Stop The Seventy Tour campaign itself I had never really appreciated those preliminary skirmishes and in many ways the chapter on the Rugby tour is the highlight of Barbed Wire and Cucumber Sandwiches. It is, of course, a serious matter and not one that is calculated to or should cause amusement but there is one particular episode from the Rugby tour took me back to a less sophisticated time and made me chuckle. It arose out of a plan that was to, effectively, hijack the coach that was to take the South Africans from their hotel to Twickenham for the Test against England.

The problem in executing the plan was that it needed someone to infiltrate the South African party, and the movers and shakers in the campaign were almost all what were described at the time by the majority of British people over the age of thirty as ‘long haired layabouts’ and therefore assumed to be agitators. The plan therefore was to get an attractive young woman to seduce one of the players and use that as an achilles heel, but that failed when the targeted player got himself too drunk. In the end it took the only one of the organisers who had a short and back and sides to dupe the coach driver, safely ensconced in the driver’s seat and ready to go, into returning to the hotel thus allowing this apparently respectable young man to nip into his seat and drive off.

Eventually, of course, the tour was called off, but not until after a great deal of toing and froing and much being said on all sides. The story is recounted here in detail and the arguments and counter arguments rehearsed, as they must be in any balanced account. It is however, for the benefit of those who were not around at the time, worth underlining one point. In the 21st century the concept of apartheid is wholly repugnant to any right minded person, as is the idea that that there could be any justification for allowing a nation that practiced such an abhorrent way of life participate in world sport.

In the 1960s however the world was a different place, and whilst many disapproved of apartheid that did not extend to a wish to interfere with the way in which South Africa ran its internal affairs. In short there were plenty of people around who did not in any way support apartheid, but who simply did not see it as the role of the outside world to interfere in South Africa’s internal affairs. It was the so-called ‘baby boomers’ who were determined to secure change and whilst they certainly had sympathisers, and one or two vociferous ones, in the corridors of power the ultimate success of the campaign is a tribute to the youth of the day and their determination to overcome the very considerable hurdles that the establishment put in their way.

The importance of Colin Shindler’s account lies not so much in the comprehensive and well written account he gives of what happened over the course of the campaign, but in the fact that he was able to discuss the events with those involved, and in particular the man who is now Baron Hain of Neath in the County of West Glamorgan. Other notables interviewed included Mike Brearley, Ray Illingworth and Robin Marlar.

Finally there are a couple of other aspects of Shindler’s book that I found particularly enjoyable. The first is the account that he gives of the five match series between England and the Rest of the World team (including five South Africans) that replaced the tour. No doubt by virtue of those matches swiftly losing the Test status they were initially given they have little importance now, but for those of us who remember them there was some magnificent cricket played and, particularly at Lord’s, a wonderful performance from Garry Sobers who showed just why he is, in the minds of all those who saw him play, quite simply the finest all-rounder the game has seen.

The second digression concerns Hain himself. I was aware that a few years after the campaign the South African Secret Service were, supposedly, behind an attempt to discredit him and set him up to be convicted of a bank theft in which he was most certainly not involved . What had passed me by though was a private prosecution launched against Hain by barrister Francis Bennion in the aftermath of the cancellation of the tour which resulted in a ten day trial at the Old Bailey in the course of which Hain was eventually convicted of one out of four conspiracy charges, for which he received a financial penalty of £200 (about £3,000 in today’s terms) – it is certainly a curious twist in the tail of a fascinating account.

Leave a comment