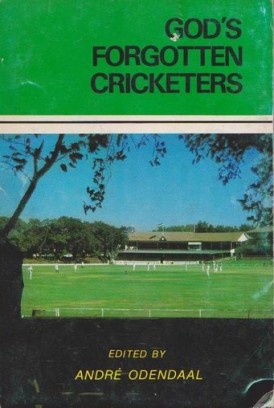

God’s Forgotten Cricketers

Martin Chandler |Published: 1976

Pages: 151

Author: Odendaal, Andre (Ed)

Publisher: The South African Cricketer

Rating: 3.5 stars

Andre Odendaal is an academic historian from South Africa. He edited this selection of profiles of South African cricketers when he was just 22. A few years later he enjoyed a brief First Class career of his own, initially for Cambridge University in England, and then for Boland back in South Africa. A batsman, he made one half century against Leicestershire on debut, but didn’t manage that again in his other 25 First Class matches, although he was man of the match in a losing cause for an innings of 74 against Warwickshire for the Combined Universities in the 1980 Benson and Hedges Cup.

A few years later, in the mid 1980s, Odendaal became the only white First Class cricketer to play in the premier competition for black cricketers in the apartheid era. Given that background and his life in academia it is perhaps no surprise that the best part of thirty years after God’s Forgotten Cricketers appeared Odendaal wrote a history of non-white cricket in South Africa, The Story of an African Game.

Had God’s Forgotten Cricketers been published anywhere other than in exiled South Africa I might have questioned the title of this collection of 16 essays for being overly melodramatic. But without any experience of it an outsider cannot possibly understand the way of life in South Africa in those days, and I can readily accept that is how it must have felt to those involved in the game. For a number of the men featured however they are in reality prime examples of ‘once seen never forgotten’. In that category there is an essay from Louis Duffus, then the eminence grise of South African cricket writing, on Graeme Pollock. There are also pieces from a variety of writers on Mike Procter, Barry Richards and Eddie Barlow.

Some subjects in the book are names that are well known to those who followed English county cricket in the 1970s, men like Clive Rice, Brian Davison, Ken McEwan, Lee Irvine and Hylton Ackerman. In the future the giant seamer Vintcent Van Der Bijl would play county cricket as well, with great success. So too would another pace bowler, the decidedly sharp Rupert Hanley, known as ‘Spook’ because of a shock of blond hair, although he would not show quite the form that Van Der Bijl did.

Of the remaining five subjects in the book, just one name was truly familiar, in that I had heard of him in the 1970s. Denys Hobson was a leg spinner, clearly highly rated and an unusual animal in South Africa. It has always struck me as ironic that the first successful South African side was built around a quartet of wrist spinners, yet there have been so few subsequently. I recall Hobson because Kerry Packer signed him for World Series Cricket, but he never played. Odendaal himself contributes the pen picture of Hobson, and a very good one it is too.

Another name I had heard was that of Ismail ‘Baboo’ Ebrahim, the context being those to whom apartheid denied a fair crack of the whip. Both his stats and Syd Reddy’s words suggest Ebrahim was as good a left arm orthodox spinner as South Africa has produced. Two other non-whites feature, off spinning all-rounder Abdullatief ‘Tiefie’ Barnes, a veteran of 35 by the time God’s Forgotten Cricketers was published, and a black African, Edward Habane. The Habane essay is one of Odendaal’s, and when he wrote it he clearly had high hopes of Habane, who was shortly to travel to England in order to further his cricketing development. In the event Habane only ever played a single First Class match and, Odendaal having set the scene here, it is partly in the hope it will tell the rest of Habane’s story that makes me so keen to seek out a copy of The Story of an African Game.

And that leaves just one name unaccounted for. There is of course a whole generation of white cricketers who missed out on a Test career because of the country’s isolation. Some travelled overseas in order to make a living from the game and became known, but plenty of others chose not to. I have read a little about some men from that latter category; batsman Henry Fotheringham, quick bowler Dave Brickett and wicketkeeper ‘Tich’ Smith are three of them. Left arm spinner Pelham Henwood’s is not a name I recognised, but it is he who makes up the sixteen.

The production of the book is not the best. It is a standard paperback that does not take the knocks too well and is not printed on the best quality paper. It is generously illustrated nonetheless and whilst the images might have been familiar to readers of the South African Cricketer very few jogged my memory. Some of them are excellent, and for some reason my mind kept superimposing the face of Temba Bavuma on the photograph of Edward Habane.

With the benefit of forty years of hindsight I would rather have seen the essays on those who had a Test career replaced with the stories of Fotheringham, Brickett and Smith, not to mention two ‘players of colour’, Howie Bergins and Winston Carelse. But God’s Forgotten Cricketers can only be judged by the standards of its times. It is an excellent book and represents an auspicious writing debut for its editor. Unlike his cricketing debut however I hope, once I track down The Story of an African Game, that God’s Forgotten Cricketers will not prove to have been the peak of Odendaal’s writing career.

Leave a comment