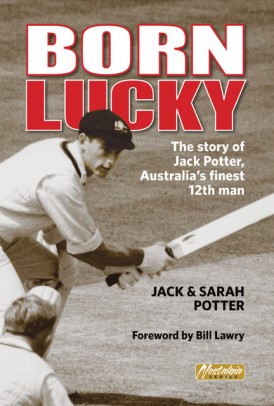

Born Lucky

Martin Chandler |Published: 2021

Pages: 259

Author: Potter, Jack and Potter, Sarah

Publisher: cricketbooks.com.au

Rating: 4 stars

I have to say that reading Born Lucky was, and I suspect I will be one of many to say this, a humbling experience. Jack Potter has achieved an astonishing amount in his 82 years, and at the end of the book his reader is left suspecting that he has a few adventures left in him yet.

But first things first. Who is Jack Potter? Certainly for those outside Australia he does need some introduction. Potter was a decent batsman for Victoria in the 1960s and, in the somewhat self-deprecating style that characterises the book, makes much of the fact that no Australian cricketer has been twelfth man for the Test side as often he has (three times) without ever winning a cap, playing up that achievement on both the front and rear covers and also, of course, at various points in between.

His playing career apart Potter’s reader will learn that he has done many things with his life, but perhaps his greatest gift to the game of cricket was during his tenure as the first Head Coach at the Australian Cricket Academy back in the late 1980s.

By the time I had got to the end of Born Lucky I have to say that I found myself liking Jack Potter immensely, so much so that I have even forgiven him for unleashing Shane Warne on an unsuspecting world. He is a man of firm views, but he does not waste words and his story moves along at a fair old lick. There is a bit of humour, plenty of positive comments about people with whom Potter has interacted and a bit of criticism for some as well.

Some autobiographies, and indeed biographies, fail to properly explain where their subject has come from, preferring to move on to the main event as soon as possible. Potter however takes time to explain his background, and how his parents lived their lives. All in all the account of how opportunities arose for his parents and the Australian way of life in the early decades of the twentieth century is an illuminating one.

Unusually for a man who went on to achieve so much there was no history of sporting prowess in the Potter family, but it certainly wasn’t just cricket at which young Jack excelled and one national side he did get to play for was the Australian baseball team. Potter skilfully tells the story of his schoolboy experience and his rise through the grades to state cricket for Victoria and then to the very brink of the Australian national side. He was called into the squad for the MCG Test of the 1963/64 home series against South Africa and, although disappointment awaited him in terms of his non-selection, he did have the pleasure, during one of his forays onto the field as sub, to use his baseball skills to run out South African opener Eddie Barlow in a manner which would have been more than familiar to one of his South Africans opponents, legendary fielder Colin Bland.

His failure to break into the Test side notwithstanding Potter did enough in that Australian season to secure a place in the 1964 Ashes party which left for England under Bob Simpson. The soft early season English pitches were not to his liking however, and by the time he did run into some form the die was cast and the limit of his involvement in the Test series were those two further appearances as twelfth man.

Although Potter clearly enjoyed his tour it ended badly for him when, in the match against the Netherlands at the end of the trip, he suffered a frightening injury when batting on the matting wicket. Potter was hit on the temple by a short pitched delivery during Australia’s shock defeat. The fractured skull that he suffered as a result meant that Potter was unable to travel back to Australia with his teammates.

Once Potter did return he might have been forgiven for having second thoughts about any sort of cricket career at all, but he stuck at it and the captaincy of Victoria passed to him for the 1966/67 season when he masterminded a wholly unexpected Sheffield Shield victory for a young and inexperienced side. Rightly treated as one of the highlights of the book that achievement is also showcased in another of Potter’s publisher’s books, Against All Odds, by Ken Piesse and Mark Browning.

Much of Potter’s time after he left cricket was spent in academia, both in Australia and for a year in the US state of Minnesota where did a Masters Degree. At various times he was also engaged in coaching, some commentary and other cricket related activities before in 1987 he became the first head coach of the Australian Cricket Academy.

In some ways sadly for the rest of the cricket world, and England in particular, Potter’s revolutionary outlook to coaching was a great success and, despite opposition in a number of quarters, the Academy flourished producing Warne, Justin Langer and many other Test players over the years.

In time however Potter became frustrated by certain aspects of the administration that he had to deal with and he left the Academy after three years. His first stop after that was a complete change in that he bought and ran a cafe bar in Adelaide. The story of himself and a friend trying to fit some new steel doors to the bar’s premises to improve security is one of the many endearingly entertaining aspects of the book.

The cafe bar having been sold Potter might have done many things, but he chose to traverse Australia for a year in a camper van. After that he relocated to England to take up a job as coach at Sedbergh School in Cumbria, and other ventures in England followed before he eventually returned from there to the southern hemisphere and time in both Australia and New Zealand, where he now lives.

Along the way, perhaps unsurprisingly, the pace of life put strains on relationships and Potter’s current wife and co-author is his fourth, although with so much else going on in his life that he wants to tell his readers about the breakdown of the relationships is not something that Potter dwells on.

Of those who receive some criticism one surprise to me was that of Simpson. Potter acknowledges Simmo was in a different class to him as a batsman, but interestingly Potter is critical of his captaincy methods. Another man who does not come out of Born Lucky too well is the ultimately tragic figure of the South Australian captain at the time the Academy started, David Hookes.

Graham Halbish, the man who was the cause of the frustration that brought Potter’s three year stay at the helm of the Academy to an end, is someone else not portrayed in the best of lights. Ultimately however Born Lucky is a ‘feelgood’ story brimming with positivity and despite his 82 years the closing chapter sees Potter, a heart attack notwithstanding, still hoping to carry on being lucky, and with his sights set on one last century – it is a splendid attitude.

Potter, his wife and all those involved in the production of Born Lucky deserve great credit for this book which is produced in a limited edition of 500 copies, the first 221 of which are individually numbered and signed by Potter and his wife. In the past I have been a little concerned that books in this publisher’s Nostalgia Series are bound in boards rather than cloth and a dust jacket, but I begin to wonder now whether perhaps I am wrong and Ken Piesse is right, given that the now ten books in that series stood together on my shelves cut an impressive dash. This one, like the others, is highly recommended.

Leave a comment