The Old Bald Blighter – Part I

Martin Chandler |

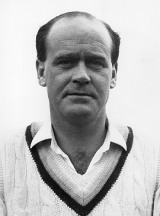

One of the more remarkable characters produced by English cricket Brian Close was, certainly in his native Yorkshire, a legend as much for the power of his personality as for his considerable contribution, in terms of runs, wickets, catches and leadership, to Yorkshire’s cause over more than twenty years. Close’s 22 Tests brought him, statistically, modest rewards and in the rest of the country his name does not resonate through the years in quite the same way but his best remembered attribute, his unflinching courage, guarantees him respect whenever his name is mentioned.

Close was a young man of many talents and had he not chosen a career in professional sport could have taken advantage of the opportunity for a University education and, doubtless, a lucrative career in business. In the event a man who was a talented footballer as well as a cricketer preferred to make a career from his sporting rather than intellectual abilities. His signing of professional terms with Arsenal, in the early 1950’s the greatest team in English football, promised much but after turning up late for a reserve game as a result of Yorkshire’s refusal to let him leave Lords early during a pre-season match, he was given a free transfer. During the 1952/53 season, having joined Bradford City, he suffered a knee injury which ended his football career and for many months threatened his future as a cricketer as well.

To return to Close’s cricket he made a spectacular entrance to the game in 1949 when, at the tender age of 18, he became the youngest man to complete the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in an English season and the first to do so in the season in which he made his First Class debut. Neither record has been broken or equalled since and barring a revolution in the way the game is organised in England never will be. Another record that Close achieved that season was that of playing in a Test match for England in his debut season – in that he was not and is not alone but the other two to have achieved the feat, Kent wrist spinner Douglas Carr in 1908 and Lancashire’s Ken Cranston in 1947, were years older and their circumstances different.

On the field Close is best remembered for his batting. He could be resolute in defence but only if his team’s circumstances demanded that he bat that way. All other things being equal Close was an aggressive left hander who always looked to score runs quickly and who hit the ball very hard indeed. His bowling was either right arm medium paced seamers or, latterly, off breaks. Above all Close was unselfish as his first Test appearance showed. He was selected to play in the third Test against New Zealand. Walter Hadlee’s tourists had been given four Tests in 1949 all, doubtless because past experience suggested to MCC they would be no match for a full strength England, of three days duration. New Zealand had been crushed by an Australian team which lacked Bradman in 1946, but perhaps the MCC should have looked more carefully at aTest against England in 1947 which, while ruined by rain, suggested that the New Zealanders batting was actually rather stronger than the carnage wrought a year earlier by Tiger O’Reilly and Ernie Toshack suggested it might be. The New Zealand batting, buoyed by the appearance of Martin Donnelly, did have enough to draw all four Tests. Close, batting at number nine on debut, came in to bat with England desperate for quick runs in order to try and establish a winning position. Close could surely have been forgiven for concentrating on at least getting off the mark but true to his beliefs he immediately went for the bowling and was well caught on the boundary off the orthodox left arm spin of Tom Burtt for a duck. His bowling was economical but he took only one wicket and he was one of three bowlers who were not retained for the final Test as the selectors shuffled their hand in the hope, unfulfilled, that they could break the deadlock.

National Service restricted Close’s 1950 season but he was granted special leave of absence to allow him to join Freddie Brown’s touring party for the Ashes series of 1950/51. The tour began superbly for Close as he scored his maiden century in the opening First Class fixture as well as taking four of the 14 Western Australian wickets that fell. Sadly that was to prove the high point of a thoroughly miserable tour for Close who returned home prior to the New Zealand leg of the tour with a groin injury. He did play in the second Test, but scored just one run in his two innings. He was undoubtedly treated harshly by the rest of the party who seemed to interpret his youthful exuberance as arrogance. Faults in his technique were ruthlessly exposed by, in particular, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, and on what was not the happiest of tours anyway Close was denied the guidance he needed from his captain and senior players and the negative tour report he received from Brown undoubtedly hindered his international career. Despite a Test career that would, on and off, extend over a further quarter of a century the 1950/51 series was the only overseas tour party Close was ever selected for.

His National Service over Close played his second full season in 1952 and did the double again, but the legacy of his footballing injury meant he missed almost the whole of the 1953 season and as the years passed he increasingly became a batsman who bowled rather than a genuine all rounder. Further Test selection finally came Close’s way for the fifth and final Test against South Africa in 1955. The series had been an exciting one with England taking the first two Tests only for South Africa to come back to win the next two and bring the series to an exciting climax at the Oval. South Africa’s revival had been brought about by the pace of Neil Adcock and Peter Heine, the off spin of Hugh Tayfield and the strangling left arm medium pace bowling of Trevor Goddard. The selectors decided that the right tactics were to select two left handed opening batsman and Close and Lancashire’s Jack Ikin found themselves plucked from the County circuit. For Close it was his first Test for five years. In the case of Ikin it was his first for three years, and also proved to be his last. The selection worked as England won that deciding Test. Close’s contribution was steady rather than spectacular but he recorded scores of 32 and 15 and earned a place on the England “A” tour to Pakistan the following winter. This was a controversial tour best known for an incident when a number of England players, Close included, “kidnapped” one of the umpires and doused him with water after a number of controversial decisions. It was fortunate for a number of the young tourists that their manager, Geoffrey Howard, and Captain, Donald Carr, were not of the Freddie Brown school of management.

The visit of the West Indies in 1957 brought two more Test caps with modest results and there was a single appearance, on home soil at Headingley, against the 1959 Indians when Close took five wickets, before he next courted controversy in 1961. Weight of runs including five centuries and seven fifties meant that Close had forced his way into the Test side by the fourth Test of an Ashes series that was standing at 1-1. The Australians won that fourth Test, all blame seemingly being placed at Close’s door without, hindsight would suggest, any justification.

England dominated the first four days and at one point Australia were just 157 in front with their last pair at the crease. Alan Davidson and Graham McKenzie were then allowed to add 98 for the last wicket, and England were set a challenging 256 to win with just under four hours of playing time left. After two hours and five minutes Ted Dexter, having just scored 76 at almost a run a minute, was dismissed and England Captain Peter May quickly followed him. Close was in next although he had questioned the wisdom of his joining Raman Subba Row at that stage given that they were both left handers. With May at the crease however he had no alternative but to go out to join Subba Row, and May gave him no indication as they passed on the field that the situation was anything other than that England were still going for the runs. Benaud was by now bowling defensively into the footmarks outside Close’s off stump and getting a great deal of turn with his legbreaks. Close could see that any right hander was going to struggle to score at any speed against the defensive field that was set and he reasoned that if he hit Benaud with the spin to leg he might be able to knock him out of the attack. There was one huge six quickly followed by a mishit that resulted in a catch to backward square leg which was gratefully accepted. The rest of the England batting could not then play out time and Australia ran out winners by 54 runs, and by virtue of a comfortable draw in the final Test they won the series 2-1. Most observers, and most importantly the England selectors, chose not to examine too closely the Australian last wicket stand, Benaud’s shrewd bowling and captaincy or the failure of anyone other than Dexter and Subba Row to make a contribution with the bat in the England second innings and instead decided to condemn Close’s innings as reckless and irresponsible and therefore to blame him for the defeat. One person, and perhaps the one best qualified to pass judgment thought Close’s actions to be the best tactical option for him but no one who mattered was too interested at the time in what Benaud had to say on the subject.

In 1963, by now 32 years of age, Close was given the Yorkshire captaincy which he held for eight years in four of which the Championship was won. With this responsibility the England selectors also deigned for the first time to select him for more than two Tests in a series and he played in all five Tests against Frank Worrell’s West Indians in what was a gripping series. On their previous visit in 1957 England had comfortably beaten the West Indies and they had won a series for the first time in the Caribbean in 1959/60, but Worrell had united and inspired his team who beat England 3-1. Unusually the most famous game of the series was the one drawn encounter, the second Test at Lords where Colin Cowdrey, batting at number eleven and with a broken arm, famously came out to help David Allen survive the final deliveries. It had been a marvellous match both sides being in with a great chance of victory as England ended up just six runs short of their target with that one wicket standing. In the England run chase Close had scored 70, which was to remain his highest Test score, memorably walking down the wicket towards the fearsome Wesley Hall and Charlie Griffith in order to disrupt them. Close never had a problem with taking blows from a cricket ball on his unprotected body, pain was all in the mind for him, and there are famous photographs of his bruised and battered body after that innings which vividly illustrate just how fearless he was.

Unfortunately for Close while he scored more than 300 runs in the 1963 series, and passed fifty on two other occasions, he did not score sufficiently heavily to set his place in stone and a poor start to 1964 meant he was not selected against Australia. Back in Yorkshire Close’s form for Yorkshire was moderate so it was to be 1966 and another rampant West Indies side before he was recalled again for the final Test. Mike Smith had led England to defeat in the first Test, and Colin Cowdrey had done likewise in two of the following three before injury ruled him out of the final game. England needed an inspirational leader and turned to Close. They did well to restrict West Indies to 268 on first innings but then found themselves deep in trouble at 166 for 7 before the last three wickets added a remarkable 361 to give a first innings lead of 259. The West Indies were bowled out for 225 with a day to spare as England recorded a morale boosting victory. Close’s personal contribution with the bat was minimal but he marshalled his team superbly and out thought his counterpart Gary Sobers. The most telling Close moment came in the tourists second innings when Sobers came to the crease. Sobers was averaging over 100 for the series and was quite capable of taking the game away from England. Close decided to play on Sobers liking for the hook shot and instructed Sussex fast bowler John Snow to bounce him. Close inevitably stationed himself at short leg. Almost every other unprotected fielder who has ever played the game would have ducked and turned as Sobers shaped to smash the ball straight at him but not Close. As ever he stayed at his post and, after Sobers mistimed the shot and edged the ball on to his body, the new England skipper was there to catch the rebound and with that bring the game to an end as a contest.

There was no England tour that winter and as the incumbent Close was reappointed for the visits of India and Pakistan in 1967. Although again his personal contributions were workmanlike rather than spectacular only a trademark rearguard action from Hanif Mohammad at Lords prevented England winning all six of the summer’s Tests and it appeared that at long last, with the 1967/68 tour to the Caribbean set for that winter, Close would finally tour again and indeed would do so as Captain and have the opportunity to do battle with Sobers over a full series. Sadly it was not to be as those in authority who were opposed to Close managed to contrive a situation where he could be censured for his conduct in a County Championship match that took place at Edgbaston late in the season.

The facts of the incident are simple enough the home side being left just over 100 minutes in which to score 142 for victory. If Yorkshire could hang on to the draw they would gain two points which might have been the difference between them between them winning the title or not. Warwickshire ended the game on 133-5 so nine runs short. The controversy arose because Yorkshire had bowled just 24 overs in those 100 minutes, and while an over rate of 14.40 may not raise too many eyebrows today it was distinctly slow by the standards of 1967. Close was hauled over the coals by a committee at Lords. He was, as ever, unrepentant and he filed a full answer to the charges. He cited the damp conditions and the need to constantly dry the ball (which could only be done under the supervision of an umpire), the fact that his pace bowlers operated throughout, and the need to regularly change his field as the Warwickshire batsmen changed their tactics. Close also pointed out that the light rain falling for a good deal of the time would, in his opinion, have fully entitled him to ask the umpires to take the teams off the field yet he at no time wasted time by pursuing such a request.

It certainly seems to this writer that Close had a number of excellent arguments but perhaps the best view would come from the attitude of the Warwickshire players. Sadly that is something it is not easy to readily discern the only man whose views this writer has found in print being those of Tom Cartwright, as expressed to his biographer Stephen Chalke the best part of forty years later. It should be remembered that Cartwright and Close later had an excellent working relationship at Somerset but certainly the book gives the impression that Cartwright found nothing in Close’s tactics that justified the formal censure that followed. With that went the England captaincy and indeed Close’s place in the tour party – Cowdrey took over the reins again and we can be certain that the irony was not lost on Close when Cowdrey’s subsequent success was the subject of much pointed criticism in the Caribbean on the grounds of the slow English over rates, which on occasion certainly dipped below 14.40.

The next controversy that Close became embroiled in was at home in Yorkshire. He was called to a committee meeting after the close of the 1970 season and, without warning, given the choice of resigning or being sacked. The expressed concerns of the committee were Close’s perceived antipathy towards one day cricket, his reluctance to engage with and bring on the younger professionals and his own increasing vulnerability to injury. In the way of the man Close opted for dismissal and at the age of 39 he joined Somerset and proceeded to demonstrate with a vengeance just how flawed the Yorkshire committee’s reasoning was.

Firstly Close turned one of the cinderella sides of the County Championship into genuine contenders particularly, strangely enough, in the one day game. In fact remarkably, for a man supposedly so averse to that form of the game when, in 1972, England were casting around for a Captain to replace the injured Ray Illingworth in the first ever series of ODI’s in this country it was the 41 year old Close who was chosen and who led England to a 2-1 victory over Australia. Secondly, for a man who had a poor relationship with younger players he did remarkable things with those in Somerset particularly two young men named Botham and Richards who went on, of course, to achieve some fame and who both give Close full credit for his role in their cricketing development. As for Close’s injuries there undoubtedly were some but Brian Close, the man who refused to ever flinch no matter how hard he was hit, was not a man to let an injury get in the way of playing. The fact remains that in every season at Somerset, except his last in 1977, Close’s batting average was better than it had ever been at Yorkshire – the century he scored for Somerset in a 10 wicket victory over his old county in June 1971 must have been one of the more satisfying moments of his career.

By the start of the 1976 season Brian Close was 45 and remarkably, as Part II of this feature will begin to describe, his best remembered moments in Test cricket lay in front of him rather than in the past.

Nice work Martin – one of the great characters of the game.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 13 February 2010

Another great article. Correctly recognises the Gooners’ pre-eminence too. :happy:

A quick glance at my “Arsenal Who’s Who” reveals the great man scored 2 goals in 5 games for Arsenal Reserves in the Combination League & 11 in 19 for Arsenal “A” in the Eastern Counties League.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 15 February 2010

Wow. The past is a different country indeed. Feel as tho I should’ve already known that tho as an Arsenal fan.

It’s weird to think that had they been born 50 years later chaps like Close and the Comptons would almost certainly have just been footballers rather than cricketers. Makes me wonder how good a cricketer Phil Neville might’ve been had he been borm 50 years earlier too. Tim Cahill (as an Aussie presumably not one to praise poms lightly) said he was a better cricketer than footballer.

Altough given his footballing prowess that might’ve been a backhanded compliment too.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 15 February 2010

Great piece Martin. Regarding the time-wastng charge, IIRC the issue was exacerbated by Close taking his players off when the batsmen and umpires stayed on, also the last two overs took 15 minutes leaving Warks just 9 runs short. Still sounds like the selectors were looking for an excuse though.

Comment by Dave Wilson | 12:00am GMT 18 February 2010