The Man Who Humbled The Don

Martin Chandler |

Whilst he was earning his place in cricket history Eddie Gilbert was, in the eyes of the law, a second class citizen. He lived his life under the control of others, for no reason other than being an indigenous Australian. His financial affairs, housing, employment and even his marriage were looked after by the Chief Protector, and there were few things in life he did not need permission to do.

Eddie wasn’t a cricketing prodigy, and indeed did not play the game until he was 15. As a child he was much more interested in throwing boomerangs. But he eventually did pick up a cricket ball. He was around 5 feet 8 inches in height with a wiry build and exceptionally long arms. From a short shuffle to the crease of about four paces a full swing of those long levers and a snap of the wrist propelled the ball at remarkable speed towards the batsman.

His progress was not as rapid as his bowling, but Eddie soon became a local celebrity around the Cherbourg settlement (originally the Barambah Aboriginal Reserve)and slowly climbed up the ladder until, on All Hallow’s Eve 1930, he stepped out (having first obtained permission to do so) at the old Exhibition Ground in Brisbane for his First Class debut, for Queensland against South Australia.

In short bursts the speed Eddie generated was electrifying, and for Don Bradman he was the fastest bowler he ever faced. Disappointingly for Eddie though he was something of a one trick pony. There was no swing, seam or cut to go with the pace, so his career record is not quite so striking as his reputation. That much conceded in a period when fast bowlers’ hearts were easily broken in Australia his 87 wickets at 28.98 in 23 First Class matches over five seasons was something he could take pride in. More importantly he tangled with Bradman the Great on three occasions. Twice he came out on top, and the first of those three meetings is the stuff of legend.

Eddie’s great triumph took place at the ‘Gabba in November 1931. It was the eighth match of his First Class career. The early stages of the game gave no hint of the drama to come. The home side won the toss and batted. After the start of play was delayed by rain they were all out for 109. Hugh ‘Pud’ Thurlow then bowled a maiden over at Jack Fingleton before Eddie took the ball and Wendell Bill prepared to face him.

Bill wouldn’t have been fazed by facing Eddie. He had played in both matches against Queensland the previous season. In Brisbane he had scored 153, and was unbeaten on 93 when time brought the curtain down on the return. He had seen plenty of Eddie in the course of those two innings, and his unorthodoxy would not have taken him by surprise.

The first ball of the over kicked viciously off the green surface and flew towards Bill. He ducked, but in the manner of an inexperienced club batsman attempted to shelter his head behind his bat. The ball took the edge and flew to debutant ‘keeper Len Waterman. The crowd of 4,000 or so roared, and Bill made his way back to the pavilion. The new batsman was Bradman. He had missed the previous season’s fixtures so his last meeting with the Queenslanders had seen him record a then world record individual score of 452. There was no Eddie Gilbert then however.

The crowd was on tenterhooks. After his exploits in England in 1930 Bradman was a hero to all Australians, and the confrontation with their own team would have brought some mixed emotions for those in the ground. The first ball Bradman faced would have calmed a few nerves. It was distinctly quick, but blocked firmly by The Don. There was no run.

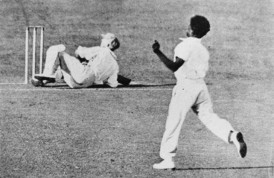

There was drama aplenty with the third delivery of the over. The ball climbed steeply at tremendous speed towards Bradman’s head. He took a desperate manoeuvre in order to get under the ball. He couldn’t completely escape as the peak of his cap was clipped, and to compound his discomfiture he lost his balance and ended up on his backside.

Beating the mighty Bradman all ends up must have done wonders for Eddie’s self belief, and the adrenalin must have been coursing through his veins. Perhaps he was even a little over confident? In any event delivery four was something of a waste in that it was wide of off stump and Bradman was able to watch it fly harmlessly by.

Eddie’s tail well and truly up the fifth ball of the over was the one Bradman later described as the fastest he ever faced. He tried to hook the ball but it was too quick even for him and for the second time in the over he lost his balance. This time the ball did hit the Bradman bat, and fell just short of third slip. More dramatically for the first and last time in his career the force of the delivery was such as to knock Bradman’s bat from his hands.

The brevity of Eddie’s run, and consequently his walk back to his mark must have further unsettled Bradman who had no time to gather his thoughts. No doubt on spleen he essayed another hook at the sixth delivery of the over. Once more he failed to middle the ball, but there was a top edge and Waterman took the catch high above his head. The world’s greatest batsman turned on his heels and walked back to the pavilion. What must the incoming batsman have thought? Alan Kippax was the New South Wales skipper. A fine batsman who evoked comparison with Trumper, Kippax was a veteran now and not entirely comfortable against high pace. It must have been almost an anti climax when he kept out the last two deliveries of the eight ball over. For Eddie it was a double wicket maiden.

Those first six deliveries of Eddie’s over are all that matters about the match. Few remember nor care that New South Wales went on to win by the thumping margin of an innings and 238 runs. Also sadly forgotten is the match winning innings. As he so often did Stan McCabe succeeded when most around him failed, and scored an unbeaten 229.

There were mutterings in the press about Eddie’s action right from the start, when he made his debut against South Australia in November 1930. In the two matches against New South Wales that followed it was openly suggested that he threw. The risk of him being no balled was one of the reasons put forward for Queensland not taking Eddie on their southern tour. Another, and perhaps more pressing for some, was that because he was an indigenous Australian he was socially unacceptable. In the end the majority at a team meeting favoured Eddie’s inclusion, but skipper Frank Gough, who is often portrayed as the villain of that particular piece, was not the only one who wanted him left out.

As for the Bradman duck despite his side’s comprehensive victory the New South Wales manager was not happy, describing Eddie’s bowling as a blot on the game. Bradman himself was interviewed by former Australian leg spinner Arthur Mailey for a newsreel. There was some discussion about the famous dismissal before, in closing, Mailey asked Bradman; And what do you really think of Eddie Gilbert? Bradman looked around, as if to check there was no one to overhear his response, and then whispered in Mailey’s ear. Whatever was said made both men laugh as the picture faded out. Not surprisingly this rankled with Eddie.

Bradman did not go into print about his thoughts until his autobiography, Farewell to Cricket, was published in 1950. By then Eddie would not have known nor cared what his former opponent wrote about him, but Bradman’s use of the word ‘suspicious’ on two separate occasions left his reader in no doubt as to his thoughts.

At this point in his career Eddie became the subject of a particularly nasty witchhunt. An influential sporting magazine, The Referee, was the cause. The writer who hid behind the pseudonym ‘Red and Black’ raised what on its face was a perfectly reasonable point. A judgment needed to be made about Eddie, and if his action was fair he should be selected for the forthcoming Test series against South Africa. The problem was that ‘Red and Black’ raised the issue constantly, from slightly different viewpoints and quoting different individuals. Everything on its face appeared even-handed, but in truth the sheer volume of material built up an unstoppable head of steam against Eddie.

A month after his greatest day Eddie was brought down to earth with a bump. In a remarkable act of bravado Victorian umpire Andrew Barlow announced in advance an intention to call Eddie in the clash with Victoria at the MCG. In his first over Barlow was at the bowler’s end and called him four times. The over had to be completed at half speed. Put on from the other end Barlow proceeded to call him again from square leg. It must be doubtful whether he had considered that his actions would bring a hostile reaction from the crowd towards himself, but they did. Despite Melbourne being home territory for Barlow and the Victorian batsmen Eddie was certainly not viewed as the villain.

Eddie was never no balled for throwing again after Barlow’s interventions in December 1931, and indeed four years later, by which time Eddie had a slightly longer run but had not really changed his action at all, Barlow allowed him to bowl throughout a Shield match unhindered. By then however the damage had been done. His chances of playing against South Africa gone with Barlow’s first effort the only other opportunity for Eddie to play for Australia would have been against England in 1932/33.

As things turned out Eddie was injured until just before the fourth Test of the ‘Bodyline’ series, due to be played at the ‘Gabba. Unsurprisingly the Australian public wanted him called up on his home ground so that the Englishmen could be given a taste of their own medicine. Eddie did play for Queensland against the tourists, but his return was a disappointing 2-93. Given the implacable opposition of Australian skipper Bill Woodfull to any form of retaliation it must be unlikely he would have got the nod even with a clutch of cheap wickets. At least he and his many supporters had the satisfaction of knowing that he had hurt the hated Jardine, struck a fearsome blow on the hip by Eddie at the end of the first day as England began their reply to a disappointing Queensland total of 201.

Did Eddie throw? He was filmed, and passed that test, and had some ringing endorsements along the way, most notable amongst them from the tragic figure of Archie Jackson who took a century from his bowling a few month’s before tuberculosis claimed him. Jackson expressed himself to be quite satisfied with the fairness of Eddie’s bowling. Perhaps a more important approval came from George Hele, a Test match umpire who stood in all five of the Tests in 1932/33. The reality simply seems to have been a lack of belief that it was actually possible to generate such pace from a short run without throwing. In addition the race card cannot be ignored. By the 1930s only a handful of the indigenous population had ever played First Class cricket in Australia. How strange that the three of them who were fast bowlers, Jack Marsh and Albert ‘Alec’ Henry were the other two, were all amongst the slightly larger handful of men who had been no-balled for throwing.

It was to be more than 18 months after the 32/33 season ended before Eddie next played a Shield match. He came back into the side for the games at the ‘Gabba against Victoria and New South Wales in January of 1935. Queensland lost both matches, but it was an auspicious return for Eddie. He had a five-fer in each game, and altogether took 14 wickets at 18.21. Unusually for him Eddie very nearly helped his side to victory with the bat against New South Wales. Chasing 310 to win he came in at 239/9 and smashed what was to remain his best ever score, an unbeaten 34, before his partner was out with 29 still needed.

Moving forward four years after that famous day at the ‘Gabba Bradman faced Eddie for the second time. By then, December 1935, Bradman had moved to South Australia and the game was at the Adelaide Oval. There is no doubt that the indignity inflicted in those five deliveries had been preying on the Don’s mind. Against a disappointing Queensland attack, including Eddie struggling with a new twelve pace run, Bradman scored 233. In Farewell to Cricket he wrote that he had obtained revenge.

Although Bradman did not refer to it in his book there was in fact a third meeting with Eddie a few weeks later in the return fixture at the ‘Gabba. In the meantime Eddie had made the headlines again after being no-balled at the SCG in the intervening game against New South Wales. It was not for throwing this time, instead Eddie found himself the first man in Australia to be no-balled for intimidatory bowling. As with the throwing episode he had the sympathy of the vast majority, who could see no comparison between the line he adopted when the England bowlers of three years previously had been allowed to bowl without interference.

In fact the SCG controversy coupled with his poor form, having taking just eight wickets at a cost of 551 runs all season, meant that there was considerable speculation as to whether on merit Eddie should make the side for the visit of South Australia. In reality however the interest generated by the renewal of the rivalry with Bradman ensured there was never a realistic chance of his being left out.

In 1930 Bradman had come out well on top in his personal duel with Harold Larwood. In 1932/33 Larwood had evened up that particular battle but, sadly, circumstances dictated that a ‘decider’ would never happen. At the ‘Gabba Eddie not only had his decider but won it. Bradman scored 31 that day but faced only seven deliveries from Eddie who was back to something approaching his top speed. His first delivery to Bradman, straight after he came in, caught the edge and was taken by the gully fieldsman on the half volley. Another inch and it would have been a second duck. After that Bradman took a two and two singles before Eddie took a breather. When he came back it was like a replay of the first delivery save that this time the ball carried comfortably to gully. The post lunch crowd, swelled significantly by the prospect of the contest were delighted. As with four years before Queensland went on to lose heavily, by 10 wickets, but Eddie had won his personal battle, and ended up with 5-87. Three weeks later in a low key encounter Eddie played his nineteenth and last Sheffield Shield match. The encounter with Victoria was drawn with the visitors’ taking first innings points. Eddie at least went out on some sort of a high, his figures being 5-107 and 1-33.

Eddie’s birth was not documented and there is no official documentation confirming the date, although 1 August 1905 is now generally accepted, so Eddie was not yet 31 at the end. With Queensland cricket in the doldrums the QCA decided that they wanted Eddie to come to Brisbane to live for the 1936/37 season. That meant they needed the permission of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals in order to take him away from Cherbourg. They got the consent they needed, although the report of the Superintendent at Cherbourg opposing the request is interesting, and at the same time rather sad; Gilbert is not a very good example of what a native should be. He is lazy and will not work. Also he is always in mischief with women. Eddie must have changed. In his younger days he had impressed the same Superintendent, who had encouraged his cricket career.

Sadly the move did not work out and Eddie never got into the state side. After a few weeks the QCA decided they had no further use for him. He was returned to the Chief Protector and thence to Cherbourg with a request that his cricket gear be laundered at the Association’s expense and then returned to them. It seems a rather callous way to send Eddie on his way. His pace was down and he had a shoulder problem, but he seems not to have been given a fair chance. There is some suggestion that his behaviour had disappointed, although nothing was ever publicised and whilst the Cherbourg Superintendent knew Eddie well, unlike Test batsman Bill Brown, his views do not sit comfortably with those of Brown who, in relation to those occasions on which he skippered Eddie, told his biographers; He was a good fellow. He did what I asked him to do.

Work was found for Eddie back at Cherbourg, initially as an auxiliary in the local hospital. His main duty was handing out medication, something which he seems to have done with the panache of the waiters he had seen in Brisbane. This was noted by his employers, although it is not entirely clear whether they approved or disapproved. The cricket world had not completely forgotten Eddie though, and he was selected to play for a Queensland Country XI in December 1936 to face Gubby Allen’s England side. He pulled out at the last minute with a shoulder injury, although it seems more likely that he simply couldn’t face the expectations.

Another problem for Eddie was alcohol. Strictly speaking it wasn’t allowed at Cherbourg, but Eddie found ways of acquiring it, and when he had the chance he would drink all he could get. His employment moved on to the railways, and there were occasional games of cricket. Unsurprisingly the former First Class cricketer enjoyed some success, both with bat and ball, but the last record of him playing district cricket was in the 1938/39 season, so still only 33.

Around 1940 Eddie fathered a son, named Eddie after his father, but the mother sadly died either in childbirth or shortly afterwards. At this stage Eddie was separated from his wife Edie, a long suffering lady with whom he had no children. After the birth Eddie senior disappears, before the last record of his playing cricket appears in 1943. He bowled on the first Saturday of a two day game, but didn’t turn up for the second day.

A degree of stability returned to Eddie’s life in 1945 when he and his wife were reconciled. They both got six month exemptions to leave Cherbourg to work, but within that time Eddie was gambling again and living rough. From then until the end of 1949, by then an alcoholic, his life followed the same cycle. There would be a few days work here and there, punctuated by bouts of drinking and gambling.

Following his admission to the Cherbourg hospital in December of 1949 the decision was made to transfer Eddie to Brisbane General Hospital where he was assessed as being violent, confused, noisy, uncooperative, no interest. He was sent from there to Brisbane Mental Hospital, later Wolston Park and now known as the Park Centre for Mental Health. Tests showed he had syphilis and a diagnosis of General Paralysis of the Insane was made. How the syphilis was contracted has been a matter of some speculation. One opinion is that the condition was hereditary and other more colourful suggestions are that the disease was contracted whilst visiting a brothel when a Queensland player or from a white woman who he encountered during his cricket career.

The treatments Eddie received were many and varied. The most notable were antibiotics and, in order to induce an artificial fever, the injection of malarial blood. The now largely discredited electric shock treatment was also tried, doubtless without any sort of consent from Eddie. Informed consent from the patient would now be a prerequisite in those few cases where merit is still seen in the procedure.

By 1950 Eddie was a lost soul. He was rarely communicative and prone to violence, both as victim and perpetrator. An excellent biography by Mike Colman and Ken Edwards contains the at times conflicting thoughts of friends and family members who visited Eddie over the next few years. His wife visited him for a while, but gave up when she became convinced there was no hope of recovery. One person who wasn’t permitted to visit when he showed an interested in doing so was illegitimate son Eddie Barney. Eddie junior was a sportsman too, representing Australia in the 1962 Empire Games in Perth as a flyweight boxer. He was a teenager when he first asked to visit and was turned down. Later he did see his father.

As time passed the wider world forgot all about Eddie Gilbert until, in 1972, writer David Frith decided to write the final chapter of his story. Believing his subject to be long dead Frith, as he always did, located the right trail and followed it to Wolston Park. He was amazed to learn that far from being deceased Eddie was alive and still at the hospital. The November 1972 edition of The Cricketer contained a moving and beautifully written account of Frith’s quest and how he finally met Eddie. He found him to be a shell of a man, and was unable to have a conversation with him although he did get a partial signature, and got to shake Eddie by the hand.

Eddie died on 9 January 1978 at the age of 72. A post mortem revealed no trace of syphilis so that must have been resolved by one or more of the early treatments he received, and so the disease never reached its most serious, tertiary, phase. The correct diagnosis was in fact Alzheimers, something that retrospectively explained many of the behavioural traits Eddie had demonstrated over the years.

The body of the old fast bowler was taken back to Cherbourg for a funeral that was paid for by the QCA. There were a goodly number of mourners who attended and he was buried in the local cemetery, albeit in an unmarked grave. Thereafter it might have been thought, given the way he had descended into obscurity from the late 1930s, that after his death Eddie would be forgotten once more.

In fact the memory of Eddie has not gone away and whilst not being remembered amongst the front rank of Australian cricketers most people with any interest in the game’s history are familiar with at least the bare bones of his story. It helps to have been the only man ever to have knocked a bat from the hands of Australian sport’s greatest icon, and a nation’s guilt over the way in which the indigenous population were treated in Eddie’s time is also a factor. Doubtless also relevant is the surge in interest in the Bodyline series that began with the fiftieth anniversary in 1982, something that has never really abated. Likewise the issue of illegal actions, so regularly raised in recent years, inevitably throws up Eddie’s name. It is something his reputation has benefitted from, the consensus seeming to be that to the extent there may have been a problem it was hyperextension, and therefore not in truth an issue at all.

In 1998 Queensland Cricket founded the Eddie Gilbert Cricket Program with the goal of providing coaching and support for native Australians. In the 21st century someone remembered the unmarked grave and in 2007 a headstone featuring details of Eddie’s bowling record lifted the cloak of anonymity from the corner of Cherbourg cemetery where his remains are interred. A more striking visual commemoration was unveiled in Nov 2008 at the Allan Border Field in Brisbane, a life sized bronze statue of Eddie at the end of his delivery stride. Finally in 2015 the cricket ground at Wolston Park was renamed the Eddie Gilbert Oval at a ceremony attended by many of Eddie’s descendants. It seems certain now that the man who might well have been the fastest bowler to ever play the game is not going to be forgotten again.

Leave a comment