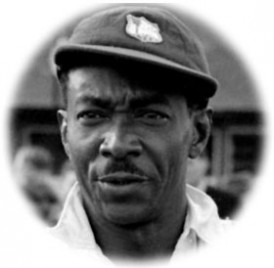

The Black Bradman

Martin Chandler |

For many years George Headley was third in the list of names of those with the highest batting averages, an all but meaningless 0.14 of a run behind Graeme Pollock. For now though Chetashwar Pujara has eased Headley out of the medal positions, as did Mike Hussey a few years ago, but as on that occasion I suspect that the great Jamaican, appropriately nicknamed “Atlas”, will be reinstated in the not too distant future.

Time treats the reputations of some players better than others, and Headley is a man whose stature seems to increase with every passing year, and his name is often thrown into the ring very early on when cricket talk turns to the subject of the game’s all time greats. The question that prompted me to write this feature, given that I have always been conscious of the fact that in a significant number of his Tests he did not face the best England attack available, is whether Headley was indeed “The Black Bradman”, or whether history treats a very fine batsman with just a little too much respect.

One of the better known pieces of cricketing trivia is that Headley is the only Test cricketer to have been born in Panama, and indeed up until he was ten years of age his native language was Spanish. His mother and father were however West Indian, Jamaican and Barbadian respectively. Headley senior worked on the construction of the Panama Canal, and when that was completed in 1914 the family moved on to Cuba.

It was 1919, by which time he was 10, that Headley went to live with his mother’s sister-in-law in Jamaica, so that he could go to an English speaking school. It was there that he was introduced to cricket, although he excelled at all the sports he tried, including baseball.

Despite his aptitude for the game the fact that Headley went on to enjoy the career he did is, effectively, down to clerical error. In early 1928 he was due to travel to the USA to join his parents, an opportunity to study dentistry having been set up for him. Had his papers arrived from Panama in a timely fashion he might never have played a First Class match, but they were late, so he was able to play for Jamaica in three matches in February against a side that former England captain Lionel Tennyson brought to the Caribbean. In those fixtures the 18 year old Headley scored 409 runs at 81.80, including one innings of 211, and thoughts of the USA and dentistry were abandoned.

One of the matters of regret in the career of Headley is that a man who had already clearly indicated that he was destined for great things was not then taken to England for the inaugural Test series between England and West Indies in 1928. The reason given at the time was that he was too young, although given the way that cricket in the Caribbean was organised in those far off days it might just as easily have been for political reasons – the selection of 17 year old Derek Sealy for the return series in 1929/30 certainly casts some doubt on the “age” point.

Had Headley travelled in 1928 he would surely have found his way into the Test side, and been able to test himself against one of the greatest of all fast bowlers, the Notts Express Harold Larwood, as well as the great medium pacer Maurice Tate. As it was by the time Headley did get to England in 1933 Larwood’s Test career was over, and Tate was a veteran, and no longer in the England side. I would not seek to suggest that Headley might have changed the course of that 1928 series, but it must surely be the case that England would not have secured an innings victory in each of the three Tests had they had him to deal with.

By the time the return series was played in 1929/30 Headley was into his third season as a First Class cricketer, and he played in all four Tests. He scored a century on debut, twin centuries in the third match, and 223 in the fourth and final Test to give him an aggregate of 703 runs, at an average of 87.87. Even the mighty Bradman had not done that well in his first Test series and, had Headley not failed twice in the second Test on the unfamiliar mat at Queen’s Park in Trinidad, a 100+ average was there for the taking.

The problem that we have though is that were the 1929/30 series played today the matches would certainly not have been given Test status. Firstly England had another team, in New Zealand, playing Test cricket at the same time. The team in the Caribbean was certainly stronger than that in New Zealand, but was nowhere near the full strength of England. Of those who had gone to Australia with Percy Chapman twelve months previously only 40 year old Patsy Hendren went to the Caribbean, and only he (twice) and Bob Wyatt (once) appeared against the Australians in 1930.

The England attack that Headley faced was therefore some way off the best England could put in the field. It was led by left arm quick Bill Voce, then 20, who did go on to prove himself a class act. Voce’s new ball partner was the 42 year old Middlesex amateur Nigel Haig, whose only previous Test experience was one match against the 1921 Australians. Haig did pretty well in the Caribbean, but was never going to provide a severe examination for a top class batsman. There was a great left arm spinner in the England side, but Wilfred Rhodes was 52 and understandably past his prime. Another Middlesx amateur, Greville Stevens, was the England leg spinner, and he took five wickets in each innings of the first Test, but the second match marked the end of his Test career. The other main bowler was Leicestershire all-rounder Ewart Astill who was 42 by the end of the series. Astill was an off spinner, who was at times close to medium pace, and while his record in his 9 Tests is by no means a bad one, he was never selected to play against Australia.

A year later Headley was part of the first West Indian touring party to visit Australia. It was a chastening experience for the visitors in many ways as the home side secured four big wins in the first four Tests before, thanks to a bit of luck with the weather, some excellent batting from Headley and Frank Martin, and a brave declaration, the final Test was won. Headley, playing against the full strength of Australia scored 336 runs at 37.33 which are not the figures of an all time great. That said not too much should be read into the bare statistics. These were new conditions for Headley, and a new attitude amongst the opposition. The Australian spinners quickly worked out that the way to deal with Headley was to bowl at his legs, and as a result he had a torrid time after a good start to the tour. It was much to his credit that he managed to adjust his game in time to record a century in the third Test, and then to play that match-winning innings in the last.

In 1933 Headley made his first trip to England for a full tour, and a three Test series. He was the great success of the tour, scoring 2,320 runs at 66.28. There were seven centuries along the way, two of them doubles and three others in excess of 150. None of the tourist’s other batsmen were able to average even 40, and Wisden described Headley as head and shoulders above the rest, before going on to say in all his innings Headley exhibited a sound defence and at the same time very remarkable stroke play. He was a fine cutter, but the outstanding feature of his methods was his powerful and well-placed driving, in which he very often went back on to his right leg and forced the ball away at the last possible moment.

Headley wasn’t quite so effective in the Tests, averaging 55, but there was one superb innings, an unbeaten 169 at Old Trafford which put his side in a strong position. It was a great shame the match only had three days allocated to it as a fourth day might just have seen a West Indies victory, which would have gone some way to making up for the disappointment of the first and third Tests following the same pattern as those in 1928.

The 1933 series was played against a full strength England side, but still one with issues. Shortly before the West Indians arrived England had returned from Australia following their 4-1 victory in the Bodyline series. Spearheads Larwood and Voce did not figure against the West Indies, and Gubby Allen played in only the first Test. So Headley once again did not face the full might of England’s best bowlers. It would have been fascinating to see how he would have batted against Jardine’s fast leg theory, but as it was the only time the tactic was deployed in the series Headley was in the field, as Manny Martindale and Learie Constantine unleashed their own brand of Bodyline, and until Jardine showed how such bowling could be tamed, it looked at one stage as if they might set up a winning position at Old Trafford after Headley’s fine innings.

The West Indies next challenge was the England side that travelled to the Caribbean in 1934/35. Despite their ultimately comfortable win in 1933 the selectors had still learnt little from their failure to win the 1929/30 series – it had been drawn 1-1. All of the major batsmen, with the exception of Herbert Sutcliffe, were selected, but the bowling was a different story. This time the West Indies triumphed 2-1. Headley’s average was a Bradmanesque 97.00, and he scored an unbeaten 270 in the final Test.

Only Essex fast bowler Ken Farnes, of those who played in the 1934 Ashes, made the trip, and he missed two of the Tests. The only other pace bowler in the party was “Big Jim” Smith of Middlesex, a smiter of huge sixes, and a consistent seamer at county level, but he only ever played a single Test against New Zealand outside this tour. In the two Tests that Farnes missed Smith shared the new ball with skipper Wyatt, whose right arm medium pace brought him just 18 wickets in his 40 Tests. The main spinners were slow left armer George Paine and leg spinner Eric Hollies. Paine had topped the averages in 1934, but he played all his Tests on this tour. Fellow slow left armer Hedley Verity, who some would argue is the greatest spin bowler who ever lived, wintered at home. Hollies on the other hand was the finest bowler of his type in England at the time and a man who, had he not been such a poor batsman, would surely be remembered today for rather more than bowling Don Bradman for a duck in his final Test innings.

The last international cricket played before the Second World War was in England in 1939 when Headley and the West Indies toured once more. They lost the three Test series, but only 1-0. Headley emerged with great credit from the defeat in the first Test, his twin hundreds being all that kept his side in the game. Overall he didn’t score as many runs as on his previous visit, his total being 1,745, but at 72.70 his average was higher, as was his mark in the Tests, 66.80. The lack of support from his teammates was also emphasised by the statistics. There were some occasional bursts of brilliance, not least when Kenneth “Bam Bam” Weekes scored a run a minute 137 in the third Test, but overall for the tour the fact that the second highest placed West Indian averaged 30.83 amply illustrates the reliance on Headley.

It is also impossible, certainly at this distance in time, to criticise the England selectors choice of bowlers. Schoolmaster Farnes was not available until August and, as he often was, Bill Bowes was overlooked, but those quibbles apart England were at full strength. It is also worth noting that if, as rarely happened in those days, the English averages were combined with the tourists’, then Headley was more than eight runs clear of Wally Hammond. Len Hutton, Denis Compton and the rest of the cream of English batting were still further behind. In 1933 the same exercise would have placed Headley third, although Hammond and Phil Mead, two of the most prolific runscorers the county game has ever seen, would have been only marginally in front of him.

If truth be told Headley should have called it a day when Test cricket returned to the Caribbean the best part of nine years later. He was in his 39th year when Gubby Allen’s understrength England side toured in 1947/48, and his Test average stood at 66.71. He had however been appointed captain of Jamaica and, for the first and last Tests of the four match series, of West Indies as well. Headley scored 25 in the first innings of the first Test followed by an unbeaten 7 from last man in after he had had problems with his back. Those problems led to him missing the second and third Tests as well. He desperately wanted to captain the side in the final Test in Jamaica, and after getting some practice in the first of the two preliminary matches between the Jamaican side and the tourists he asked to be rested from the second to avoid further stress on his back. Fearful no doubt of the drop in gate receipts that would follow the request was denied, and the back duly played up, and Headley missed the fourth Test as well.

The following season was to be marked by West Indies first tour of India which, understandably, Headley wanted to be part of. He struggled to acclimatise and failed in the first Test before sustaining an injury trying to take a catch off his own bowling. Headley was an occasional leg spinner, who got a few wickets in England in 1933, but seldom bowled after that and never took a Test wicket. In a non-First Class game before what amounted to an unofficial Test against the fledgling nation of Pakistan he was given the chance to turn his arm over and took 6-49. Not surprisingly when the Pakistan openers put on well over 100 in the next fixture he was thrown the ball again and removed them both. It was in falling awkwardly on his side, later realised to be a fracture, that he suffered the injury that meant he played in no more of the Tests in what proved to be a batsman’s series.

West Indies next Test action was in England in 1950 when, after losing the first Test, they stormed back to take the next three and the series. Headley was in England as well, playing league cricket, it not having proved possible to agree terms for his inclusion in the touring party. There was some agitation for a late call up after the first Test defeat, but understandably the side’s subsequent successes soon quelled that. After his countrymen returned home Headley settled in Birmingham, to play as a professional for Dudley in the Birmingham League. There was never any question, come the winter of 1951/52, of Headley repeating his trip to Australia of more than twenty years previously, and his Test career appeared to be over.

In the event however it was not. There was at this time a large Jamaican community in Birmingham that kept their countrymen back home regularly updated with news of Headley’s dominance of Birmingham League attacks and in 1954 there was a wave of public clamour, encouraged by The Daily Gleaner to get Headley back to the Caribbean to play against Len Hutton’s England side. The newspaper opened a subscription account and, more than GBP1,000 being raised, a somewhat apprehensive Headley returned home. He was all but 45. In his first game back he split the webbing on his hand, and then he suffered a nasty arm injury after being struck by Fred Trueman during his first encounter with the tourists. He was advised to take six weeks off, but that would have spelt the end, so just over a week later he played through the pain for Jamaica against the tourists and, in the second innings, made an unbeaten 53.

The whole of Jamaica celebrated the news of his call up for the first Test and they had a win to celebrate, by 140 runs, but they would have been saddened by the performance of their hero. Headley’s scores were 16 and 1, and he scratched around looking a shadow of his former self. This time it was the end, albeit the match itself came back to haunt the main protagonists a couple of years later.

When Hutton published his autobiography in 1956 he admitted to having instructed his side to give Headley “one off the mark”. His rationale was said to be that he didn’t want to risk antagonising the crowd by dismissing the great man without scoring, a view doubtless shaped by what had happened later in a series much marred by crowd disturbances. For Headley’s part he knew he had been given that run, but believed it to be for the sound tactical reason that, his having come in to face the last ball of an over with just a single over left before the interval, that Hutton wanted that last over to be bowled to the new batsman. Headley was understandably indignant, and a long letter from him was published in the The Daily Gleaner .

So how good was Headley? Do the statistics tell the whole truth or is it the case that, when measured against the quality of the bowling attacks that he faced, that he must fall back a little from the status of second only to Bradman. It is in some ways a compelling argument, but it must also be accepted that all Headley could do is score runs against whatever bowling was pitted against him, and it is certainly through no fault of his that England’s selectors did not always accord him and his teammates the respect they deserved on their own pitches.

And there are other factors the most obvious of which is that batting must be more difficult for a batsman, like Headley, who cannot rely on anyone else for consistent support, and that was most certainly the case for him before the war. Hammond had the likes of Hobbs, Sutcliffe, Mead and Hendren to back him up, and Bradman had Ponsford, Woodfull, McCabe and Fingleton amongst others. The unreliability of Headley’s teammates was vividly illustrated by Dave Wilson, in his feature Dominant Partners , in which he calculated that on average Headley had 5.64 partners per innings, way more than anyone else. Some important statistics are that before the war Headley top scored in 15 out of West Indies 35 innings. In 11 of those he made more than a third of their runs, and in 3 more than half. It is easy to remember now the not dissimilar responsibility that rested on the shoulders of Brian Lara in much lore recent times. Over the course of his career Lara scored 18.87% of his sides runs. It is perhaps not surprising that the man who sits atop that particular table is Bradman, on 24.28%, but Headley is second, on 21.38%

Had Headley been born 20 years later, and had the support of the “Three Ws” it is interesting to speculate on just what he, and indeed they, might have achieved. But even though we can never know the answer to that question it seems to me to be pretty clear that the man who dominated the two English summers in which he was here, and held the West Indian batting together through his own efforts for a decade, is fully entitled to be regarded as one of the leading candidates for the accolade of the second greatest batsmen of all time. My initial thoughts to the contrary were not properly thought through and, on reflection, misguided.

Does that make Bradman the white George Headley? Funny I’ve never once heard him referred to as that 😀

Comment by Hooksey | 12:00am BST 29 August 2013

Thats what West Indians called him back in the day.

Comment by Coronis | 12:00am BST 30 August 2013

I think that would change if you visited Jamaica

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am BST 30 August 2013

I know people often referred to Headley as the black Bradman. What I’m saying is I’ve never once heard Bradman referred to as the white Headley.

Comment by Hooksey | 12:00am BST 30 August 2013

Chappell also made reference to the title when he was doing his synopsis of the Cricinfo ATG XI selections.

Good article overall, just felt that you made a point of highlighting the bowlers he didn’t face, but didn’t acknowledge when he did face the front line bowlers and was successful.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am BST 30 August 2013