The Biggest Hitter?

Martin Chandler |

Back in August of 2016 I read a piece by Charles Davis in The Cricket Monthly about big hitting. In essence his point was that if the likes of Chris Gayle and Shahid Afridi are unable to consistently hit a cricket ball further than around 120 metres, then how on earth can the list of big hits that appeared in James Lillywhite’s Cricketers’ Annual (‘the Red Lilly’) in 1898 possibly be correct?

The ‘Red Lilly’ states the record hit as being 160 metres, although that one, the perpetrator being engaged in promoting a new bat, is by its nature doubtful and its authenticity was not accepted by Gerald Brodribb in his 1960 study of big hitting, Hit For Six. Brodribb’s research concluded that whilst the 160 metres might well have been correct, that it was measured from hit to the point at which the ball came to rest, rather than from hit to pitch. There are twelve other strikes in the Lillywhite list however, the second being 154 metres by Charles Thornton, who is also responsible for six of the others. Otherwise only the six feet six inches tall Australian George Bonnor appears on the list more than once.

Thornton’s two biggest hits were achieved in practice back in the 1870s. He was at Hove at the time of both, potentially of some relevance as a coastal location is more likely to provide wind assistance, but even so the record seems wholly out of kilter with expectations and Davis’ scepticism is neither surprising nor unreasonable. On the other hand the assiduous Brodribb was satisfied of the bona fides of the claims made on Thornton’s behalf.

One thing that is clear from any degree of research into this question is that in Victorian times the concept of exactly how far a cricket ball could be struck with the bat was one that attracted much more attention than at any time subsequently. It was by no means unusual for accompanying spotters and enthusiasts to go to the trouble of measuring out these hits, and the integrity of those carrying out that task is therefore important.

In the case of Thornton’s Hove exploits these were overseen by James Pycroft. As a cricketer Pycroft was good enough to appear in four First Class matches. He was an Oxford graduate and a man of the cloth whose name is known now mainly by virtue of his book, The Cricket Field, one of the classics of the game’s literature. First published in 1851 the book sold well and is no rarity even today, having passed through nine editions in its author’s lifetime. A tenth and final edition, updated by the famous historian Frederick Ashley-Cooper, appeared in 1922, more than a quarter of a century after Pycroft’s death.

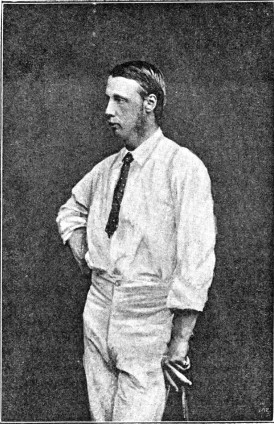

Given the number of cricketers who are not household names yet have still been the subject of biographies it is surprising that, in the twenty first century Thornton is as elusive a character as he is. But it is possible using contemporary sources to build up something of a picture of the man who, in much the same way as the same peers regarded Charles Kortright as the fastest bowler who ever lived, seems to have been generally recognised as the greatest hitter of a cricket ball that the world had seen.

So who was Thornton? He had some illustrious forebears most notably his paternal grandfather, a Member of Parliament who was involved in the campaign to abolish slavery. Thornton’s own parents both died, seemingly in different situations, when he was just five years old but whatever problems that situation brought it seems money was not one of them. Thornton went to live with a paternal Aunt who was married to the Archdeacon of Canterbury. The Reverend Benjamin Harrison was a cricket lover and made sure Thornton was educated at Eton College and Trinity College Cambridge.

At Eton Thornton appeared for the first eleven in each of his final three years at the school, and was captain in the last of those. His reputation for being a hitter developed then and in his final year he astonished all in the traditional annual encounter with Harrow by hitting the ball over the pavilion at Lord’s. This was 1868, so the building was not the same one as that cleared by Albert Trott* in 1899 for what remains the only time ever, but it was still a notable feat, the more so for an 18 year old.

It was also at Eton that Thornton acquired the nickname that he was to carry throughout his days, ‘Buns’. In his obituary in Wisden the grand old man of Kent cricket, Lord Harris, explained why. The two were playing together in a practice match when a wicket fell, with Thornton fielding in the deep. He took advantage of the break in play to buy a ‘bun and jam’ from a vendor near the boundary. Before he had finished his refreshment the next delivery was bowled and the ball was hit high in Thornton’s direction. The catch was duly completed without a bun in sight, although his Lordship was unsure as to whether that had been swiftly consumed during the ball’s flight or put in Thornton’s pocket.

In terms of how Thornton approached his batting that was summed up neatly by Gerald Brodribb as his chief aim in batting was always to hit the ball, and to hit it a long way, not wildly like a tail end slogger, but with control, immense power and the utmost joie de vivre.

In terms of technique we have got used to watching big powerful men stand firm, get their front legs out of the way and slog the ball to all corners. It seems however that that was not the Thornton way. He was not a small man, his six foot tall frame being a substantial one by the standards of a century and a half ago, but despite that his physique was not a particularly impressive one. In his case his power came not from his upper body but from a leap down the wicket towards the ball and a full swing of the bat.

There must also have been considerable speed in Thornton’s reactions as well, and his timing was good. Inevitably he missed the ball on some of his forays towards the bowler, but he was generally quick enough to get back before being stumped. He also wore very little protective equipment. By his time batsmen had started to wear pads, but other than what amounted to a couple of shin pads placed inside his socks Thornton rejected leg guards. As for gloves they were something Thornton only adopted late in his career, and even then he would only wear one on his right hand.

In 1866, at just 16, Thornton made a First Class debut for the Gentlemen of Kent against the MCC at Canterbury. It would be 31 years before he played his final First Class match, at Fenner’s for his own invitational side, CI Thornton’s XI, against Cambridge. In between those two matches there were another 215 First Class appearances for a wide variety of teams including Cambridge University, Kent, Middlesex, MCC and the Gentlemen of England. Always an amateur the most cogent evidence that Thornton wasn’t quite in the front rank was that he was invited to play for the Gentlemen in the showpiece match against the Players on only three occasions, and never at Lord’s.

By the end of his career Thornton had scored a total of 6,928 First Class runs at the relatively modest average of 19.35. There were just five centuries, three for Kent and two for the Gentlemen of England. Additionally an occasional bowler there were 47 First Class wickets for Thornton, almost all of them in the early part of his career. He was a much better bowler at a lower level, on one occasion in 1870 whilst playing for his own side against King’s School Canterbury taking all ten wickets, hitting the stumps each time. He bowled underarm at pace, unusual even then, and of course against the laws of the game today.

But no one who went to watch Thornton play expected to see him at the crease for too long. His story is littered with accounts of prodigious hitting, starting with that straight hit at Lord’s in 1868, described by John Lillywhite in his Cricketers’ Companion (‘the Green Lilly’) as the biggest straight drive he had ever seen.

The two longest hits were, as noted, performed in practice. The longest in match conditions seems to have been at Canterbury in 1870, so when Thornton was 20. The description at the time was that he drove the ball so hard, so high, and so very far, that it went clean over the spectators and bounded into the adjoining road. The Festival Secretary measured the carry at 139 metres. The same distance was also given for a hit against the Australians in 1878, but no named ‘supervisor’ was put forward in relation to that one.

The measure of Thornton seems to almost always be the frequency with which the ball left the grounds of the day. At the Oval he hit the ball over the pavilion several times, and through his career failed to exit the ground on only one of its four sides.

Another happy hunting ground for Thornton was the Cambridge University ground at Fenners. Of one straight drive in 1885 it was written he made one drive off a slow bowler which sent the ball clear over the north wall and over the tennis courts beyond. One witness described the distance as at least 150 yards (137 metres). Given the permanent nature of the landmarks referred to it is unfortunate that no one seems to have actually measured the distance whilst they were still present.

Perhaps Thornton’s favourite ground of all was that at North Marine Road in Scarborough where in later life he was to do much to establish the annual festival which, in various forms, has continued to this day. In 1886, so towards the end of his playing career, it was at Scarborough that Thornton played what he himself considered his finest innings. He was leading a Gentlemen of England side against the famous wandering club, I Zingari. Thornton won the toss and batted and went out to open the innings with WG Grace. Despite the presence of Grace and future England captain Drewy Stoddart the Gentlemen were all out for 90 and I Zingari, who numbered four Test players in their side, took a lead of 209.

In the Gentlemen’s second innings Thornton changed the batting order so that Grace batted at four and himself at six. All seemed lost when the fifth wicket fell at 133 with both Grace and Stoddart back in the pavilion. Thornton then took charge and when the last wicket fell seventy minutes later he was unbeaten on 107. His innings featured eight sixes and twelve fours, so there was not too much running to do on a warm afternoon. It is worth remembering that in those days to score six the ball had to leave the ground, and not simply clear the boundary.

Two of the sixes have passed into Scarborough folklore. The first went through a second floor window at the rear of a three storey terrace in Trafalgar Square and, so the story goes, came perilously close to hitting the elderly female resident. Shortly afterwards an even bigger six cleared the terrace albeit striking a chimney on the way over. It was a remarkable hit not so much because of the distance (subsequently measured at 126 yards) but because of the height that must still have been on the ball as it cleared the building right at the end of its flight. It was something that had never been done before and seems only to have been done twice since, by club player Gervais Wells-Cole in 1901 and, much more famously, by the Australian all-rounder Cec Pepper in 1945.

Outside of cricket it is not entirely straightforward to work out exactly what Thornton got up to and who with. He left Cambridge at the end of his fourth year at Cambridge in 1872. Harris, in the Wisden obituary, expresses regret at Thornton and Cuthbert Ottaway leaving Kent at that point to move to London to set up in business together. Ottaway is a sad figure. He was a good cricketer with a reasonable if limited First Class record but, a fellow Old Etonian, his main sport was soccer and he captained England in two of the earliest internationals.

Sadly Ottaway died in 1878, but according to his biographer the career path he chose, and the reason for his move to London, was to become a Barrister. There is no mention of Thornton in Mick Southwick’s biography of Ottaway, and nothing I have read of Thornton suggests he was ever a budding lawyer. It seems likely therefore that either a mistake has been made or that Ottaway, as well as his legal studies, had some sort of involvement in Thornton’s timber business.

To what extent Thornton’s success was self made as opposed to his wealth being inherited is unclear, but he must have made a success of the timber business, and of his time as a director of the Royal Brewery in Brentford, as when he died in 1929 his Estate was worth, in 2019 terms, the best part of five million pounds. He had a reputation for parsimony as well, although not when it came to indulging himself and activities that interested him, like cricket and motoring.

Success must have come early to Thornton given that by 1878, when he was only 28, he had his own cricket club, Orleans CC, which had sufficient prestige to be able to attract that year’s Australian tourists to their home ground in Twickenham. For the club’s second First Class fixture, against the touring Australians of four years later, Thornton led a side that included nine Test players, including the brothers Grace, and Orleans were well on top when the game finished a day early to enable all engaged in it to spend the scheduled third day at Epsom watching the Derby.

Thornton had achieved enough commercial success to be able to retire in 1912, although he led an interesting life afterwards. In 1914 he was in Berlin, and perhaps fortunate to get out in time when war broke out. By the time peace returned Thornton, always a keen motorist, was touring Japan and Siberia and, on his return, published a book about his experiences. Throughout the 1920s he retained his strong links with Scarborough taking an eleven to the Yorkshire resort for the annual festival there including in 1929 shortly before his death.

In his declining years Thornton also took a great interest in the law, regularly attending at the leading criminal trials of the day and even, as a character witness for a disgraced banker, giving evidence at the central Criminal Court. His other favoured leisure activity was the cinema and, if Sir Home Gordon is to be believed that is what caused his death. Thornton had, according to Sir Home, been warned that the atmosphere in cinemas was affecting his health, but he continued to attended on a daily basis, a victim it would seem of passive smoking.

*You can read more about Albert Trott in this feature. Alternatively if you want the full story of ‘Alberto’ you could invest in Steve Neal’s excellent biography, which we reviewed here.

Leave a comment