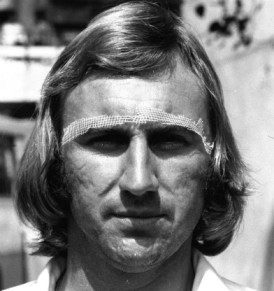

Lever of Essex

Martin Chandler |

One of the biggest complaints about the team England sent to Australia this winter was the lack of variety in its pace attack. All were right arm fast medium with not a southpaw or a real speed merchant in sight. It has been eight years now since Ryan Sidebottom last played for England and since then no left arm pace bowler has been chosen for England in red ball cricket. The selectors briefly showed an interest in Mark Footitt, taking him to South Africa in 2015/16, but he seems out of contention now he has left Surrey.

In the game’s shorter formats Reece Topley has bowled well at times, as has David Willey, but neither seem to have been earmarked at any point as Sidebottom’s successor. Perhaps the recent interest shown in Sam Curran and George Garton will see a change, but history tells us that Test quality left arm quicks rarely appear from our islands. The most prolific in terms of wickets taken remains Bill Voce, who took the last of his 98 in 1946.

Second in the list is Sidebottom with 79 victims. Alan Mullally took 58 wickets in the 1990s but ultimately proved a more effective bowler in ODIs. Yorkshireman George Hirst took 59 way back in the Golden Age, but never quite took his prodigious county form into the Test arena. Injury ended the ambitions of perhaps the two best; Frank Foster (45 wickets) and the quickest of them all, Jeff Jones (44 wickets). The only other left armer of note is the man with the third highest aggregate of wickets, John Lever, who took 73 wickets in 21 Tests spread over a decade. Curiously despite taking his wickets at the thoroughly respectable average of 26.72 there was never a time when Lever was sure of a starting berth in the England line up.

Essex born and bred Lever’s progress into the first team was assisted by the unexpected loss of Barry Knight at the end of the 1966 summer. With the veteran Trevor Bailey due to leave the game at the close of the 1967 season Essex, who could never afford to carry a large professional staff, needed to look to the 18 year old to step up to the plate. Although he was never genuinely fast Lever bowled at a lively pace from a long diagonal run and, more importantly, was able to swing the ball both ways without any apparent change of action. At the end of his first season Wisden commented that he created a favourable impression and deserved better figures. He had taken 26 wickets at 30.69 in 13 matches. It was a bowlers’ summer however, no fewer than seven Essex bowlers having a lower average, and the county had a disappointing season, finishing 15th out of 17.

Gradually Essex’s fortunes looked up, and a significant factor in the improvement was Lever’s new ball partnership with the West Indian Keith Boyce. By 1975 both were riding high in the averages and Lever was beginning to be talked of as a Test bowler, so much so that when his Lancashire namesake Peter was unexpectedly recalled to the England side there were plenty in Essex who believed there had been some sort of selectorial blunder. The following year however JK was certainly the man who did enough to win a place in the England party that travelled to India under Tony Greig. The breakthrough had come.

Out and out pace had never been particularly successful in India, so it was no surprise that Lever’s consistent success at county level earned him a place in Greig’s side. Another factor in Lever’s favour was his durability. For a pace bowler his fitness record was remarkable and given that England’s two main pace bowlers, Chris Old and Bob Willis, were notoriously fragile it was a simple decision to prefer the variety that Lever offered over the experience of his main rival, Mike Hendrick, another who was more than familiar with the treatment table.

As India were the home side they, of course, provided the balls that were used throughout the tour. Lever found these very much to his liking and did well in the early matches and consequently earned himself a debut in the first Test in Delhi. He got to put his feet up to start with as Greig won the toss and batted, but five wickets went down for 125 and batting became a hard slog. The often unsung hero of English cricket at that time, Dennis Amiss, stood firm at the top of the order and scored 179 in eight and a half hours before being the eighth man out. He had added 94 with Lever who was eventually the last man to go as England totalled 381. Lever had scored 53, and that was to comfortably remain his highest Test score.

In India’s response Willis and Old got no joy out of the new ball, but did manage to get it knocked out of shape, so Lever began his first spell in Test cricket with a replacement ball. Unlike the first this one swung prodigiously, and in the space of three sensational overs Lever sent back Anshuman Gaekwad, Jimmy Amarnath, Gundappa Viswanath and Venkat to break the back of the Indian batting. When, next morning, Sunny Gavaskar and Brijesh Patel briefly threatened a recovery Lever came back and removed them as well. With Syed Kirmani joining his list of victims shortly afterwards he ended the Indian innings of 122 with 7-46*. He got three more in India’s failed effort to avoid an innings defeat and had a match haul of 10-70.

There was a second convincing victory for England in the second Test, this time by ten wickets. There was no major role for Lever this time, but he was right back in the spotlight in England’s 200 run win in the third Test at Madras (Chennai), and certainly not in a way in which he would have wanted. In Delhi the weather had been cool, so much so that Lever had worn a long sleeved sweater. In Madras the heat was stifling and the England bowlers had problems with sweat running into their eyes. Physio Bernard Thomas went out and bought some Vaseline impregnated gauze strips. The idea was that the gauze would direct the sweat away from the eyes. It did not work and having given up on it Lever threw his strips away. The issue became contentious because he did so close to the stumps and the suspicions of umpire Judah Reuben, standing in his final Test (though lest anything untoward be read into that comment it had always been the intention he would retire after the match) were raised that there had a breach of what was then an experimental law; No interference with the natural condition of the ball shall be allowed.

Lever took 5-59 and 2-18 as India were swept aside for 164 and 83 but the Indian crowd was incensed. Cheater Lever Go Home proclaimed one banner, and Indian skipper Bishan Bedi told the press we’ve caught him cheating, adding it is disgusting that England should stoop so low. Forensic testing, unsurprisingly, showed traces of Vaseline were present on the ball. The secretary of the Indian Board announced that following a consideration of all the evidence they were unable to come to a conclusion as to the bowler’s intention. England manager Ken Barrington, seemingly in conflict with that fence sitting exercise, announced that both the Board and Bedi had accepted our explanation that this was not a direct infringement of the laws of the game. No one corrected him. Ultimately the TCCB were content to accept assurances from Barrington and Greig that nothing untoward had been going on.

Greig later described the allegations as groundless and degrading, although he did acknowledge that the swing Lever had obtained was inevitably going to raise suspicions, comparing the case with that of the Australian Bob Massie who had so discomfited the England batsman in the 1972 Ashes series. Greig was equally adamant that Massie’s success was obtained by fair means and not foul although not all his 1972 teammates had agreed at the time. Derek Randall, of the 1976/77 side, wrote that the Indians had made a mountain out of a molehill.

There was damage however. Lever remained deeply unhappy at the behaviour of Bedi, a man he had previously regarded as a friend, and treated him to a few bouncers when the pair met at Northampton a few weeks later. Bedi, no great shakes with the bat, did at least have the satisfaction of remaining unbeaten in both innings. At the end of that summer however Bedi’s contract was terminated by Northamptonshire and he lost an unseemly dispute in an Industrial Tribunal that followed. Was his conduct during the Madras Test in any way relevant to his dismissal? He certainly thought so, and the circumstantial evidence is with him on that although the official line was, naturally, that the two events were unrelated.

When Bedi extended the hand of friendship in 1977 Lever rebuffed the offer and so the schism remained throughout the pair’s playing careers. Eventually however the old rivals ended up playing together in a low key match in the 1990s. On this occasion, realising that nothing useful could be achieved by doing otherwise, it was Lever who initiated a rapprochement.

The most authoritative view of the whole episode came from Christopher Martin-Jenkins who later published an account of the tour. CMJ had no difficulty in accepting that there was no deliberate cheating by England whether in Madras or earlier in Delhi. After all if a bowler wants to surreptitiously alter the condition of a ball he is unlikely to do so with a substance that he takes out to the field with him plastered all over his face as the base of what amounted to a pair of very obvious false eyebrows. On the other hand CMJ also well understood the pressure Bedi was under as captain as the series slipped from his grasp in embarrassing fashion. Ultimately however he recognised that whilst what England attempted with the gauze strips was certainly naïve, and that someone really should have taken the tin of gauze out to the umpires as soon as Reuben, as he had every cause to do, became concerned, that there had been to intention to cheat or mislead.

Although he did not make a substantial contribution to the fourth and fifth Tests, one of which was won by India who were also on top when the final Test ended as a draw, Lever was, with 26 scalps at 14.91, comfortably top of the English averages. Moving on to Australia for the centenary Test there were two wickets in each innings of a memorable encounter that finished with Australia victorious by exactly the same margin as the inaugural match.

The peace of the cricket world was rudely shattered at the beginning of the 1977 summer when all became clear as far as Kerry Packer’s plans were concerned. Lever was as much in the dark as anyone else, Greig never having sought to involve him in his and Packer’s plans. Even if he had Lever, just embarking on a Test career he could see Packer’s actions seriously compromising, would not have been interested anyway. The distracted Australians lost the Ashes. Lever played in the first two Tests before making way for a debutant named Botham, and then came back for the last match of the series, but he only took five wickets in the series.

That winter Lever headed out with England to Pakistan and New Zealand. The Pakistan trip was not a comfortable one. The cricket was tedious and the party badly affected by illness, giving rise to Ian Botham’s well known crack about not even sending his mother in law to the country. Almost alone amongst the tourists Lever remained fit and bowled tirelessly. In the second innings of the second Test his figures were 20-2-62-0. They are nothing special at first glance, but skipper Mike Brearley considered it as important a bowling contribution as Lever ever produced. These were eight ball overs, and Lever helped hold in check a Pakistan side which otherwise might just have been able to create a winning position.

It is surprising looking back that Lever was unable to catch the selectors’ eyes in 1978 as he had a magnificent season, taking 106 wickets at 15.18 and helped Essex to the runners-up spot in the Championship. They went one better in 1979 and the title finally came to the county for the first time. The cost of his wickets was slightly greater this time but there were 106 more victims for Lever. There would doubtless have been more, but he missed two matches because of one of his occasional England call ups. Two wickets in a drawn encounter with India meant that he did not retain his place.

The 1977/78 series in Pakistan was the second and last in which Lever played a part throughout. Leaving aside the one off Jubilee Test in India, in which he did play, he was only selected for one Test in each of five series over the next three years before getting two Tests on the 1981/82 trip to India and Sri Lanka. He caused a mid innings collapse in the second Test against India, but could not prevent the game being drawn and after two wickets in the drawn third Test his tour, insofar as the Tests were concerned, was over and with it, so Lever believed, was his career at the highest level.

A meeting was called for some of the senior players during the brief stay in Sri Lanka at the end of the trip. On the agenda was a tour of South Africa which would pay a tidy sum for what amounted to a month away from home. Lever had enjoyed a decent benefit in 1980 which netted him more than £60,000, but he was still far from financially secure and took the view that at just turned 33 he would not have too many more chances. He had been to South Africa twice before, in the early 1970s, with sides raised by Derrick Robins. This side was raised by South African Breweries and comprised purely English players rather than the multinational sides that Robins had put together, but it was still somewhat naïve of Lever if, as he claimed at the time, he was surprised at the outcry the tour led to.

The South Africans billed their visitors, despite the team’s objections, as England. Although the side was largely made up of veterans it was led by Graham Gooch, still only 29 and with his greatest days ahead of him. How many more of those might there have been had the members of the party not paid for their trip with a three year ban? Lever claimed to be shocked by the severity of the ban, although most saw it coming. His 1982 summer was disappointing, perhaps by way of a reaction, but in 1983 and 1984 he was back to his very best, passing 100 wickets in both summers and helping Essex to back to back Championships.

In early 1986 England suffered their second successive 5-0 reverse at the hands of the West Indies. English cricket was at as low an ebb as it had ever been when they then lost the first home Test of the 1986 summer to India. Lever had shown some decent form in the early part of the season but, at 37 and out of Test cricket for more than four years, it was still a surprise when he was selected for the second Test.

The selectors’ logic was clear. The match was to be played at Headingley, then as now by reputation a swing bowlers ground. It was not however a ground that Lever had much experience of. Despite his twenty years in the game Essex matches in Yorkshire had generally been played on outgrounds and, suffering from nerves and being asked to bowl downhill with the wind in the wrong direction, Lever’s opening overs were wicketless and relatively expensive.

Things did get better for England and they eventually dismissed India for 272. Then the two Indian seamers, Roger Binny and Madan Lal, did the job Lever was picked to do rather better than he did and England were bowled out in 45 overs on the second day for 102. Even then with Lever rediscovering his touch and taking three wickets to help reduce India’s second innings to 70-5 at the close the match was not quite out of reach. Hope did not last for long on the fourth morning however as the Indian lower order, shepherded splendidly by Dilip Vengsarkar, established a platform which, after another inept England batting display, resulted in a big Indian victory to take the series. For Lever there had been six wickets, but he hadn’t done the job he was picked for and did not expect to be chosen for England again. In that expectation he was proved to be correct, but there was plenty of consolation elsewhere as Essex won another Championship title.

Lever retired at the end of the 1989 season, a summer that saw a two horse race for the Championship title between Worcestershire and Essex. Sadly for Lever Essex could not quite catch their rivals so he had to be content with just the four titles, to which Essex also added two Lord’s final successes, and three victories in the old Sunday League. Lever remained a quality bowler to the end, even if in the natural order of things he was not so formidable in his final three seasons as he had been in his pomp. He might have gone on a year or two longer, but an arm problem which reduced his First Class appearances hastened his eventual retirement at the age of 40. Lever still managed to go out on a personal high though, and to a standing ovation, when in his last innings against Surrey he took 7-48, eerily close to replicating his famous figures in Delhi.

After leaving Essex Lever had more than one opportunity to re-join County cricket in a coaching role, but he preferred to work with the youngsters at Bancroft’s School in Woodford Green. Later he also fitted in some work hosting parties of supporters following England’s fortunes overseas. Lever’s son, also JK and a left arm seamer, tried to follow in his father’s footsteps, but sadly James Lever didn’t quite make it.

A modest man Lever’s own summary of his career was I think I was a better than average county bowler who was fairly average at Test level. He wasn’t an all time great, and was never going to be, but he wasn’t treated particularly well by successive panels of selectors, and to one who saw plenty of his career his own judgment is an unnecessarily harsh one.

*The only other occurrence of a Test player scoring a 50 and a 7-fer in the same Test would appear to be Albert Trott, with 72* and 8/43 vs England in 1894/95

Leave a comment