From Hyderabad to Canterbury, via Karachi

Martin Chandler |

Saturday 4th September 1971 was a great day for Lancashire supporters. The Red Rose were playing Kent at Lord’s in their second successive Gillette Cup Final. In those days and for many years afterwards the denouement of the 60 over knock out was the highlight of the English domestic season.

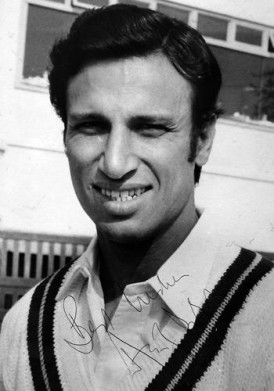

Both sides had two overseas players although the passage of time has blurred the status of Farokh Engineer and Clive Lloyd both of whom are, in the autumn of their lives, regarded as part of the very fabric of Lancashire. Kent had two Test all-rounders, Bernard Julien and Asif Iqbal, from West Indies and Pakistan respectively. In reality they had a third as well, another West Indian John Shepherd, who had a residential qualification.

Overseas players showed great loyalty in those days, which was reciprocated by the counties. Engineer and Lloyd spent 9 and 18 summers respectively with Lancashire. Julien’s name is not synonymous with Kent, but he still spent 8 years there. Asif and Shepherd were with them for 15 years.

Kent skipper Mike Denness won the toss and, given the 10.45am September start did what nearly all skippers did and invited Lancashire to bat. It was a struggle early on. Asif took the new ball and reeled off five successive maidens. Later on he dismissed Clive Lloyd for 66, but Kent’s grip was loosened and Lancashire ended up with 224.

In 2016 a side would set off in the quest for 225 to win in a T20 game with some hope. It may come as a surprise to some therefore to learn that The Cricketer described that as a formidable target, before pointing out it had never yet been achieved in the second innings of a final. Lancashire took two early wickets, and it was 56-3 when Asif came to the crease. He batted absolutely beautifully. At the other end Lancashire chipped away but, with Kent on 197-6 with plenty of time left I had all but given up.

Even ‘Flat’ Jack Simmons was struggling to contain Asif, but in his eleventh over he bowled three dot balls to him. Asif met them all with the full face of the bat, but couldn’t pierce the field. For the fourth delivery he unfurled a powerful extra cover drive. The optimism evaporated and I averted my gaze. Four surely? No. The next I heard was the normally phlegmatic Jim Laker, commentating for the BBC, shout excitedly it’s a magnificent catch, you can’t possibly see a better catch than that in a final. I looked back and waited for the replay and there was no doubt Laker was right. Our skipper Jack Bond, 39 years young, had flung himself to his right at extra cover and managed to pluck the ball out of the air. Even today commentators and pundits would have purred at the quality of the catch.

With the spell Asif had cast broken the last three Kent wickets fell for just three more runs and Lancashire ran out winners by 24. Asif’s 89 was without doubt the best innings of the match though and that, coupled with his economical bowling at least brought him the consolation of the Man of the Match award.

At that time, as far as I was concerned, the Pakistanis were as entertaining a side as there was in world cricket. Asif had a habit of performing at his best in front of the television cameras, and his brand of wristy improvisation in the limited overs game was immensely popular. His countrymen Majid Khan (at Glamorgan), Zaheer Abbas and Sadiq Mohammad (both Gloucestershire) and, cheekiest of them all, Mushtaq Mohammad at Northamptonshire were much the same. Mushtaq was the first man I ever saw play the reverse sweep.

What I didn’t realise in 1971 was that Asif was an Indian by birth, born in Hyderabad in 1943. His uncle, Ghulam Ahmed, was a decent off spinner who played 22 Tests for India between 1948 and 1959 in three of which he was captain, so Asif had a fine pedigree. After partition Asif’s family gradually migrated to Pakistan, although not before the 16 year old made his First Class debut for Hyderabad and, just over a year later, represented South Zone against the touring Pakistanis. He took six wickets, and the following season, by which time he had relocated to Karachi, he was regarded as primarily a bowler.

The Asif action was an idiosyncratic one. He was of average height and slim, and his slightly pigeon toed and bow legged run culminated in a whippy delivery stride that delivered the ball at a lively pace. He wasn’t genuinely quick by any means, but in his early days was a good deal sharper than medium pace. More importantly he made the ball wobble in the air disconcertingly and was good enough to be selected for his Test debut in late 1964 as a bowler.

Pakistan’s opponents for the match were Australia, who were on their way home from the 1964 Ashes trip to England. The Pakistanis got off to a dream start, openers Khalid ‘Billy’ Ibadulla (on debut) and Abdul Kadir put on 249. Asif scored 41 from number ten in Pakistan’s first innings, helping to stem a collapse. In the second innings he went in at three as nightwatchman, and scored 36, so his potential was clear. With the ball Asif contributed a couple of wickets as Pakistan competed on level terms with their highly rated visitors.

Next for Pakistan was a return Test in Australia, drawn again, before they moved on to New Zealand for a three match series. All three Tests were drawn. New Zealand would certainly have won the first had it not been for Asif’s first telling contributions with the bat, and he also took his first five wicket haul. His second and last came as soon as the next match and his series figures of 18 wickets at 13.77 were hugely impressive and not bettered on either side.

The success with the ball in New Zealand was despite Asif suffering a back spasm in Australia which caused him grave concern. His figures in New Zealand suggest the problem was resolved but Asif knew his days as an opening bowler were numbered. Pakistan didn’t play too much Test cricket in the 1960s and were not scheduled to do so again until they visited England in the second half of the 1967 summer. It was to be their third tour of England. On debut in 1954 they had squared the series and become, as they remain, the first country to win a Test on their first trip to England. In 1962 they had lost 4-0. The batsmen had their moments, but only once did the bowlers take even eleven English wickets in a match, and twice only five.

In January and February of 1967 an MCC under 25 side toured Pakistan and Asif was given the captaincy of the Pakistanis. He scored a century, his first, in the second representative match and was duly invited to join the touring party. At that point the back problem flared up again. Asif was tempted to keep quiet but eventually admitted he had a problem and found the management to be rather more supportive than he had feared they might be. He was given plenty of treatment, but still found he needed cortisone injections to enable him to bowl. During the series Asif bowled more overs than any of his teammates, and took the most wickets his final tally being 11 at the perfectly acceptable average of 25.77, but the problem hadn’t gone away, and the series was his last as a frontline bowler. By the end of the series he had taken 39 wickets at 23 in 11 Tests. He won a further 47 caps, but added only 14 more wickets at a cost of 43.21 each.

India had visited England in the first half of the 1967 summer and had proved disappointingly weak opponents. There were a number of commentators who expressed the view that Pakistan would be made of sterner stuff. In the event two stirring innings of great contrast apart they did not prove to be too much stronger than the Indians.

The first great innings was that of the ‘Little Master’, Hanif Mohammad, at Lord’s. Hanif batted for the greater part of ten hours for an unbeaten 187 that got his side within 15 runs of England’s first innings total. A comfortable draw resulted but although Hanif’s innings is what the match is remembered for he could not have done it without Asif. First he took 3-76 to help restrict England to 369, and then he played the only other innings of note in the Pakistan reply, 76 in an eighth wicket partnership of 130 with Hanif.

The second Test at Trent Bridge resulted in a ten wicket win for England, although the Pakistanis could consider themselves desperately unfortunate. The covers at one end had leaked and a difficult wicket gave them no chance. The prolific chronicler of early Pakistan tours, Qamaraddin Butt, came out with one of his better lines, describing the Pakistan first innings as firing like a dirty carburettor on a frosty morning.

The third Test looked like being another hammering. England’s first innings lead was 224 and when Asif came in at 41-6 early on the morning of the fourth day, a Bank Holiday Monday, arrangements had already been made for an exhibition match to take place in the afternoon in order to entertain the paying public. Asif’s pride was hurt, but when 41-6 soon became 65-8 it looked like he was just going to have to swallow it, especially as incoming batsman Intikhab Alam was having trouble with his eyesight. Intikhab had developed a nasty stye on his eye and the ointment that he had put on it was clouding his vision.

In fact Asif himself was hardly in the pink. His back had reacted so badly to the 39 overs he bowled at Trent Bridge that he had had to miss the next two matches. He was genuinely concerned that, given the top experts in England were unable to resolve the problem, it was already chronic and that as a consequence his professional career was drawing to a close. He shouldn’t have played at the Oval, but he wanted to and the selectors wanted him to, so he decided to give it his best shot. If his worst fears had been confirmed then at least he would have gone out with a bang rather than a whimper.

Intikhab was a lower order batsman good enough to end his career with a Test century, eight fifties and an average of 22.28, but Asif’s first job was to protect Intikhab while his eyes cleared. So well did he do that that Intikhab barely faced a delivery in the first six overs he was at the crease. Asif also needed to make sure that England’s close fielders did not get too comfortable, so he had to play some big shots too. As the morning wore on Pakistan passed several targets. First was their previous lowest total against England of 87, then 100, Asif’s fifty and finally the fifty partnership before taking lunch at 121-8. Of the 56 the pair had added all but six were Asif’s.

During lunch Asif learned that the exhibition match was to be one of twenty overs per side. So it might have started a trend, but he wasn’t impressed by that, even less so when he learnt that decisions for the match awards had already been made. He went out with renewed determination to frustrate the exhibition and sabotage the awards decision.

The afternoon session was wonderful entertainment. With two overs to go before tea the pair had added 190 and Asif was on 146 and Intikhab 51. Asif had batted for three hours and twenty minutes and hit 21 fours as well as two sixes. All bowlers came alike to him and he did not offer a single chance. He punished the spinners immediately after lunch and when the new ball was taken the ferocity of his assault was such that the shine was gone in half a dozen overs.

By now Pakistan were 32 in front and in with a chance of taking the game into a fifth day and giving England something to think about. Finally though England skipper Brian Close brought himself on. He tossed up a few off breaks from around the wicket. Asif hit one for four, and then thought he saw the chance to get to his 150 before tea. The half volley that Close then delivered tempted Asif down the wicket, but it was a bit shorter and wider than he thought and he missed. Knott whipped off the bails and that was that. As is often the case after such a partnership Intikhab immediately followed, swinging across the line of a straight one from Fred Titmus. England took half an hour to get the runs, losing two wickets in the process. Asif took them both and, inevitably, a further award had to be swiftly announced.

The press were fulsome in their praise for the Pakistani fightback. Ian Wooldridge in the Daily Mail writing; An eminently forgettable Test summer died yesterday on the infinitely memorable scene of Asif Iqbal, fast bowler, hitting one of the great unrequited centuries in the game’s history. It came too late to turn the course of the match, but it was just in time to reassure us that there is still more to cricket than judicial inquiries and political upheaval.

Although Asif had turned 24 shortly before the party left for England the Oval innings was only his second century. Despite his back continuing to trouble him from time to time he was able to continue playing for another fifteen years. In that time he added 43 more centuries to his record, 10 of them in Tests. When he finally retired in 1982 he was the most capped Pakistani Test player.

Twenty six of the centuries were for Kent where Asif was extremely popular. In 1970 he helped them to their first Championship since 1913. He was appointed captain in 1977 but only lasted for that one summer, standing down after he signed for World Series Cricket. Back in the ranks he helped the county to another title in 1978 before leading them again in his last two summers there, 1981 and 1982.

For Pakistan Asif was a lock in the lower middle order and part of a team that history tends to forget. The mid 1970s was the start of the pace revolution. It began in earnest when Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson destroyed England in 1974/75 and within months the first of the fearsome West Indian quartets was put together. In 1976/77 Pakistan travelled to both Australia and West Indies. They had a stroke of good fortune against Australia when Thomson broke down in the first Test, but Lillee stayed fit and firing and Australia were otherwise at full strength.

In the first Test Australia were well on top when they took a lead of 182. Asif held Pakistan together with an unbeaten 152 in the second innings and Australia were left a target of 285. The match ended in a draw with Australia 24 runs short with Pakistan needing four more wickets. Oddly and much to the irritation of the crowd the Australians, when they needed 56 to win in the final 15 overs, chose to shut up shop and made no attempt to chase down the target. That decision looked less perverse after Australia enjoyed a thumping victory in the second Test, but Pakistan squared the three Test series at the SCG. Imran Khan’s two six wicket hauls were his first match winning performance for his country and it is for that the game is remembered, but Asif’s 120 and his partnership of 115 with a 19 year old Javed Miandad were vital in securing the victory.

As Pakistan moved on to the Caribbean they might have thought they were similarly in luck as Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel were injured. The replacements however were Joel Garner and Colin Croft, and between them that pair took 58 wickets in the five match series. Asif struggled against the pace in the first four Tests, but finally came good during the deciding final match. His second innings 135 was not however enough to save his side from defeat and the Pakistanis were left to rue their inability to take the final West Indian wicket at the end of the drawn first Test.

When Asif joined World Series Cricket he announced his retirement from Test cricket, although he was soon persuaded to change his mind. He did not enjoy much success in the ‘Supertests’ against Australia, but did score a century in his only innings against Packer’s West Indians. When peace returned he was a member of the Pakistan side that played a historic series against India in 1978/79, the first time the two countries had met in 18 years. The dreary draw in the first Test featured a century from Asif, but his contributions in the next two Tests, an unbeaten 21 and 44 were much more important. Both were successful run chases and Asif’s improvisation and skills honed in ODIs and List A matches were crucial.

The final series of Asif’s career was the return trip to India in 1979/80. This was a six Test series, and Asif was appointed skipper. The series was not a happy one. India won 2-0 and Asif managed just two half centuries. He did however have what must have been an uplifting experience in the final Test at Eden Gardens as to a man the huge Indian crowd acknowledged him. In retirement Asif played a significant role in establishing Sharjah as a major cricketing centre and he was also ICC referee for the Zimbabwean visit to India in 1992/93.

In 1999 when the furore over match fixing began Asif found himself back in the headlines, but this time for reasons he did not appreciate. The former Pakistan fast bowler Sarfraz Nawaz, whilst being interviewed on live television, claimed that in the 1979/80 series between India and Pakistan rival captains Sunil Gavaskar and Asif had overridden the views of the match officials to ensure that play began on a wet wicket in return for payments received from bookmakers. When the focus of the enquiry at one point turned to Sharjah, Asif’s name inevitably cropped up again.

Was he involved? The evidence is flimsy to say the least. Sarfraz was and is a notoriously loose cannon, and doubtless long carried a grievance over his being left out of the Pakistan side for that tour of India. The fact that by virtue of that omission he wasn’t even present when the events he described took place further detracts from the credibility of a story that, as far as I am aware, has always been denied by everyone else involved. As for Sharjah responsibility for whatever may have happened there cannot, merely by Asif’s association with the organisation of the matches, be laid at his door. He has always denied any wrongdoing and that in my view should be the end of that. Asif should be remembered for what he was, a fine batsman who might well, had it not been for that troublesome back, proved to have been a Test class all-rounder.

Leave a comment