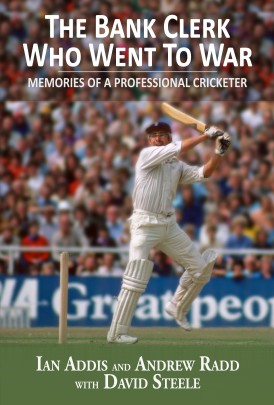

The Bank Clerk Who Went To War

Martin Chandler |Published: 2018

Pages: 223

Author: Addis, Ian and Radd, Andrew and Steele, David

Publisher: Chequered Flag Publishing

Rating: 4 stars

There aren’t many books on cricketing themes, or indeed on any subject outside the realm of what are properly described as text books, that are credited to as many as three authors. In fact only two such cricket books readily spring to mind, the first being a book about cricket on the continent of Europe, where it makes sense that a pooling of the specialist knowledge of more than one writer will produce a more comprehensive result. The second is a very different type of book, and one which has much in common with The Bank Clerk Who Went To War. Brian Reynolds is a biography of the Northamptonshire batsman whose final years in the game overlapped with David Steele’s early ones and, perhaps more significantly, Ian Addis was one of the three who authored that one.

Never a writer I presume Steele’s own role in the writing of this biography, The Bank Clerk Who Went To War, was limited to providing the material which provides the basis for the story of his life. Andrew Radd is Northamptonshire’s archivist and a journalist to boot, so I assume he and Addis are jointly responsible for the writing. If, as I would expect to have been the case, each wrote different parts of the book then they are to be congratulated on the way they have produced a seamless narrative, something which cannot be easy to achieve with two pens at work.

It is at this point that I have to remind myself that however familiar the name and deeds of David Steele are to me, and all cricket lovers of my generation, that his is not a name that resonates down the years in the same way as some of his contemporaries. Names like Snow, Greig, Edrich and Boycott get plenty of mentions on the CricketWeb forums, whereas Steele is very rarely referred to despite, briefly, being equally famous and, notably, the only cricketer between Jim Laker and Ian Botham to win the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award, an accolade he received in 1975.

In order to fully understand the impact of David Steele on the nation’s consciousness you really had to be a follower of English cricket over the Ashes winter of 1974/75. We went out there assuming, after a 2-2 draw in 1972, that we would win. Dennis Lillee, who had looked good in 1972 was, so we were led to believe, finished by injury and as for Jeff Thomson, even a lot of Australians had never heard of him.

The events that unfolded were therefore all the more distressing for being so unexpected. Late nights listening to the radio commentary were grim enough, but the daily dose of television highlights a few hours later showed just what England’s batsmen had had to contend with. Tony Greig showed some fight of course, as did Alan Knott, but those two and the courageous John Edrich apart England’s batsmen appeared to be way outside their comfort zone.

There was more of the same in the first Test back home 1975, and then a change in captain. Mike Denness resigned and to the delight of many, young boys in particular, the job went to Greig. The selectors’ made changes, but the one that was the talking point was Steele. The story was that he was a journeyman cricketer plucked from obscurity by Greig. The truth is rather more prosaic, as he did have a decent record and must have been discussed in the past, but certainly the newspapers had ignored him, and his selection was unexpected.

The second Test began much as the first had ended, and England lost four quick wickets, but then Steele and Greig steadied the ship, and Steele spend the rest of the summer making sure England did not lose again. His scores were 50, 45, 73, 92, 39 and 66. The press and public alike revelled in his success, the more so the following summer when the elusive century finally arrived in the first Test against Clive Lloyd’s West Indies. He was less successful in the rest of the series, but failed in only one match, and that was when he was asked to take on the unfamiliar task of opening the innings. Steele never played for England again however and, to his great disappointment, was not selected to tour India that winter. It was said, completely without justification, that he had a weakness against spin bowling.

The story of Steele’s brief Test career and his lingering resentment at being overlooked for India is of course part of The Bank Clerk Who Went To War, but a relatively small part. Those two summers are set in the context of a county career that stretched over 22 summers first with Northamptonshire, then Derbyshire before a final three years back at Northampton.

The way county cricket was played a couple of generations back has given us a number of interesting books this year. Rob Kelly’s biography of Robin Hobbs and the autobiographies of Alan Wilkins and Malcolm Nash all look at the era and anyone who enjoyed all or any of those is going to get just as much pleasure from reading Steele’s story, which is full of entertaining tales from the county game. In recent years Steele has earned a formidable reputation as an after dinner speaker, and I dare say that a few of the tales have grown a little in the telling, but the book is no less enjoyable for that.

As you would expect from a biography in which the subject is also part of the writing team the book gives a very clear picture of Steele the man, and picks up on many aspects of his personality as well as his game. Stories about the care he took with his money are plentiful, and he has clearly fully briefed Addis and Radd about the more Comptonesque features of his running between the wickets.

Unlike some Steele also has some interesting forebears including an England footballer (Uncle Fred) and a legendary Staffordshire cricketer (Uncle Stan). From his own generation there was a durable Northamptonshire all-rounder (Cousin Brian), and younger brother John had a long county career with Leicestershire and Glamorgan, and it was a little disappointing not to read more about John. His contribution does however come eventually, at the end of the book, and there is a particularly good story about the only time that the brothers appeared in the same team, but little of John’s personality emerges. I mention that as an observation rather than a criticism – after all the book is David’s story and John inevitably plays only a minor role, although I would think many fifty somethings who followed the county game through the 1970s and 1980s will agree with me.

Back in 1977 Steele, understandably, cashed in on his fame and published a ghosted autobiography, Come in Number Three, which is one of the better books of its type and well worth seeking out. Given its ability, forty years on, to cover the rest of an interesting life The Bank Clerk Who Went To War is inevitably a more rounded and therefore enjoyable book, but this is one of those uncommon situations when the old mid career memoir merits a look as well.

In bringing his story up to date Steele deals at much greater length now than in 1977 with his county career, and is also able to set out what life after cricket brought him. He had a successful career in the printing industry, and then another as a coach as he and former England team mate Frank Hayes produced a fine double act as master in charge and cricket professional at Oakham School. Stuart Broad is without doubt their most famous student, but by no means the only one to have succeeded. There is one aspect of Steele’s life that is not dealt with however, and that is the reason why he left printing and went in to coaching. To do so would doubtless have brought back some unpleasant memories for Steele as there was a business failure involved, but it would have given a fuller picture of the man if that part of his story had been included.

Ultimately however The Bank Clerk Who Went To War is an excellent read, and thoroughly recommended. It almost goes without saying that a book from this publisher is a well produced one, but I will add that anyway because the importance of a cricketing biography being well illustrated, having a decent index and a comprehensive statistical summary of its subject’s career cannot be overstated.

Leave a comment