Black or White*

Martin Chandler |

I am black. My grandfather and grandmother were the children of slaves born into slavery. I am neither proud nor ashamed of these things. They are facts. I had no control over them. Where or to whom we are born is not any choice of ours. I might have been you who are reading this. Or you might have been I.

Learie Constantine was the first of the the long line of cricketing household names that have emerged from the Caribbean. It is certainly the case that neither his First Class or Test records are outstanding, but the impact he made between the wars was remarkable. “Crusoe” Roberston-Glasgow began a pen picture of him by mentioning the contemporary giants of the game; Hammond and Bradman amongst batsmen, and Larwood and Grimmett amongst bowlers, before writing But of them all, Constantine alone has been the one thing to watch, the magnet of the moment, whether batting, bowling or fielding. Surely no man ever gave or received more joy by the mere playing of cricket.

As a batsman Constantine was constantly on the attack. He rarely batted for very long, and didn’t play many defensive shots. His wristwork was exceptional, and his strengths were square of the wicket. As a bowler he was fast, even explosive from his short run-up. But he was inconsistent in both disciplines, particularly in the early part of his career. His fielding was different however. In the days when it was a largely neglected facet of the game, Constantine was a revelation. His speed and agility in the covers, and his finely honed talent for throwing down the stumps became the stuff of legend, and as he grew older and wiser and realised he needed to conserve his energies for bowling, he became a fine close catcher as well, usually at slip. Thus while at the end of his first tour of England in 1923 his batting and bowling failed to stir the editor of Wisden to mention the young all-rounder, he did feel obliged to comment Constantine was an amazingly good cover point.

In 1928 the by now 26 year old Constantine was back in England for the West Indies first tour as a Test playing nation. His performances in the Tests, like those of his teammates, were disappointing as the new boys lost each of the three Tests by an innings. On the tour as a whole however Constantine did the double, and in the game against Middlesex he put in a performance that helped shape the rest of his life. Middlesex were a strong side, fielding as many as nine men who had or would play Test cricket and two of them, Nigel Haig and Patsy Hendren, scored centuries before Middlesex declared as soon as Hendren got to three figures, at 352-6, shortly after the second day’s play began. In reply the tourists had slumped to 79-5 when Constantine came in, the follow on looking certain. As to what happened next the following day’s Times summed it up as; Everything else in the day’s play was entirely put in the shade by Constantine’s batting, and it is not flattery to remark that once he was out cricket seemed to be a dreary game. The unorthodox style of the innings was demonstrated by what the paper described as …a remarkable six over cover point’s head and his straight driving of short-pitched balls.

It was a blistering interlude, but a deficit of 122, backed up by a start in the second innings of 40-2 by the home side, still left few doubting that the third and final day would see anything other than a Middlesex victory. Next morning Constantine made no immediate impact until he was switched to the Pavilion End. He then proceeded to hit the stumps four times, had two catches held in the slips which, adding in the early wicket he had taken the previous evening, gave him 7-57 and left West Indies needing 259 to win. At 121-5 it looked like they wouldn’t do it, but Constantine was not finished, and when he was out an hour later his 103 had brought them to the brink of a victory that was duly confirmed a few minutes later.

Ian Peebles was one of Middlesex’s Test men. He became a distinguished writer and later described the match. He was full of admiration for Constantine’s fielding. His abiding memory was in fact a dropped catch, but a bizarre one that was testament to the manner in which Constantine played the game. Peebles edged to third slip where a low catch went down. Somehow Constantine, from second slip, managed to flick the ball up. He had five attempts at it, covering more than ten yards in total before the ball finally eluded him. During his first innings Peebles described delivering his quick wrist spinners to Constantine with great trepidation. As to his bowling on the last morning he wrote that Constantine …suddenly took off like a man possessed. and that his pace was awe-inspiring. Of the second innings he described one drive from a delivery off Jack Hearne, another quickish leg spinner, that so damaged Hearne’s hand when he went for a caught and bowled that he didn’t play again that season – and after that the ball hit the pavilion step with such force that it rebounded most of the way back to Hearne. In 1977 Peebles summed up This was to be the greatest all-round performance I was to see in my career, possibly in my life

One of the more remarkable features of the match is that Constantine, recovering from a pulled muscle, had been advised not to play at all. He confirmed in his 1933 autobiography that had it not been for the lure of playing at Lord’s, coupled with some gentle pressure from those members of the tour management who looked after the takings, he would have sat the match out. The most important consequence was that on the back of the publicity that was generated Nelson of the Lancashire League signed him as their professional for 1929. His game was ideally suited to the format and he stayed nine seasons, during which the League went to Nelson seven times. He was enormously popular.

Constantine returned to the Caribbean in 1929/30 for the first home Test series against England, albeit in reality a second eleven. He did rather better than in 1928, although his figures were still unremarkable. In Australia in 1930/31, while he was successful in the other games, and proved as he did everywhere to be hugely popular with the crowds, his returns in the Tests were distinctly ordinary.

In 1933 West Indies were back in England but Nelson released Constantine only for the second Test. He scored 31 and 64, but his involvement is remembered mainly for the bodyline that he and Manny Martindale subjected England to. The pitch was not a fast one, but with the exception of their captain all of the England batsman were discomfited by what they faced and the match was largely responsible for opinion in England swinging away from supporting the tactic that brought home the Ashes just a few months previously.

It was 1934/35 before Constantine finally showed that he could deliver at Test level. Bob Wyatt led England in the Caribbean. The MCC had picked a stronger side than in 1929/30, especially in batting, but it was still not enough. They might have believed it was after England won the first Test, but then Constantine arrived and he made solid contributions with bat and ball in both the Tests that West Indies won to take the series.

West Indies next series, and theirs and indeed the game’s last action before the international game was adjourned for the duration of the Second World War, was in England in 1939. This time Constantine had no league committments and was available for the whole tour, including each of the three Tests. England won the first Test comfortably and Constantine contributed little, although he took five wickets in the rain-ruined second Test at Old Trafford. The third and final Test at the Oval was drawn too, but the visitors matched England and it was a great shame that there were only three days allocated. In the England first innings of 352 Constantine took 5-75 to record his Test best and, as West Indies took a first innings lead of 146, he scored a rapid 79 from number 8, out of 109 added for the last four wickets. Wisden said He revolutionised all the recognised features of cricket and, surpassing Bradman in his amazing stroke play, was absolutely impudent in his aggressive treatment of the bowling…. England, with a definite result already out of the question, then batted out time with Hutton and Hammond sharing a third wicket partnership of 264. The extra day would have made the match more than interesting, but at least Test cricket went into its enforced seven year break on the back of a spectacular exhibition played out in some balmy late August sunshine.

To all intents and purposes Constantine’s career in First Class cricket ended with the outbreak of war. He was almost 38, although six years later he did play in one final match at Lord’s when he captained The Dominions against England. He led a team that was made up of eight Australians, a South African and a New Zealander in addition to himself. Although there were to be many trials and tribulations along the way his appointment by a committee often regarded as reactionary, was an early signpost on the road to the multi-racial society that most of us are fortunate enough to live in today. The cricket itself matters little, although it was a magnificent game with two centuries for Walter Hammond evoking memories of idyllic peacetime summers, and fine hundreds for Keith Miller and New Zealander Martin Donnelly setting up a victory for the Dominions. Constantine, for once playing second fiddle in a partnership, contributed 40 to a stand of 123 with Miller that took less than an hour to put together, and as England’s run chase faded while the 44 year old could not conjure up a wicket he did, from mid-on, throw down the stumps of Lancashire all-rounder Eddie Phillipson to snuff out the challenge.

Constantine did not return to the Caribbean with the rest of the party after the tour finished early due to the tensions in Central Europe, and he remained in England where he spent his war as a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labour, looking after the interests of coloured workers. He was, as befitted one of the best known names in world cricket, much in demand for the wartime charity matches that were played up and down the country and in July 1943 was invited to play for the British Empire XI in a one day match in Guildford, and immediately afterwards for a Dominions XI in a two day encounter at Lord’s. Constantine booked a room for himself, his wife and his daughter at the Imperial Hotel in Russell Square for four nights. It is a sad reflection of the state of society at the time that he felt the need at the time he made his reservation to clarify, or so he thought, that his colour would not be an issue.

Despite the precaution he had taken it became clear, following his arrival, that Constantine and his family were not welcome. They got as far as their room before a message was received that the manageress wished to see Constantine. In the course of the discussion that followed she uttered the oft-quoted words We will not have niggers in this hotel because of the Americans. If they stay tonight, their luggage will be put out tomorrow and the doors locked. The Constantines were accomodated, without difficulty, at a nearby hotel owned by the same company, but given the treatment he and his family received, shabby even by the standards of the time, and seemingly dished out only because the Imperial did not have the courage to stand up to a comment made by an American guest as the family walked through the lobby, Constantine resolved to embark on legal action.

The first Race Relations Act did not hit the Statute Book until 1965 so a straightforward racial discrimination claim was out of the question. Constantine might have tried an action in slander, based on the contemptuous and insulting words the manageress used. But that was not straightforward. On a purely factual basis the manageress denied using the word “nigger”, and legally the issue of malicious intent might have proved problematic. Potentially this was the most lucrative way to proceed, as the likely damages were the highest, but this was one piece of litigation where financial considerations were just about at the bottom of the list on the risk assessment. The main consideration was how, after the service they had given in the war, coloured people would be treated in British society when peace finally arrived. In short Constantine might have lost, and defeat would, in certain quarters, have validated racism. It was not a risk that could be taken.

There might have been an action for breach of contract. The obvious problem with that was that damages would only have been nominal, as the Constantines were accomodated elsewhere at no extra cost. But it would still have been a victory, albeit importantly not on a point of principle, but on a technicality. Such a victory would probably have been seen as a pyrrhic one, but I am not convinced that success would be guaranteed anyway. The case was never fought on the point, so we will never know, and I am not aware of what the documents might have disclosed, but I suspect that the Hotel might well have had cause to argue, not without merit, that there was a term implied in the contract that provision of equivalent accomodation elsewhere in the vicinity was sufficient for it to discharge its contractual obligations.

So the route to court actually chosen was undoubtedly the most obscure, even in those days, and was founded on the Hotel’s breach of its common law duty, as an inn, to accomodate the Constantines. The factual issues in the case were straightforward and the law appicable to it might have been ancient, but it was not complex despite the attempts of the Imperial’s legal team to make it so. On the face of it the case had some of the hallmarks of an unseemly spat, and because of the hostilities it did not attract the media attention that in peacetime it might have, but one look at the Dramatis Personae shows just how seriously the protagonists were taking it. Constantine was represented by Sir Patrick Hastings KC, one of the best known and most able advocates of his day. His junior counsel had a glittering legal career in front of her. Rose Heilbron, then just 29, ended up with a CV that contained a long list of female firsts including taking silk (being appointed King’s Counsel), leading in a murder case (being the senior advocate), becoming a Recorder (a type of judicial appointment) and sitting as a Judge in the Central Criminal Court (The Old Bailey). The Defendant’s instructed Gerald Slade KC and Aiken Watson. Slade was not a household name in the manner of Hastings, and Watson did not achieve the same fame as Heilbron, but neither lost very much in comparison with their opponents in terms of their legal abilities. The Judge was Sir Norman Birkett, one of the most eminent of his time and a British Judge at the Nuremburg Trials. He was also a cricket man, and in 1955 authored The Game of Cricket, a delightful book showcasing the game’s depiction in works of art.

The trial lasted two days. Constantine, his tour manager and a colleague from the Ministry of Labour all confirmed his account of the meeting with the manageress. She maintained throughout that she had taken great care not to be offensive and she and a colleague both denied that the word “nigger” had been used. She did not however help her credibility when, under cross-examination from Hastings, she expressed doubt as to whether she recognised Constantine on the basis that They all look alike to me, these negroes.. Birkett had little difficulty in finding for Constantine describing the manageress as a lamentable figure, and her evidence as unworthy of credence

Not quite everything went Constantine’s way, as Birkett awarded him nominal damages only, rather than the exemplary (punitive) damages that Hastings sought, rather speculatively given the state of the law at the time. There was however clear and direct evidence available as to just how disturbed Constantine was by the incident – perhaps Hastings should have called to give evidence the seven Guildford batsmen he clean bowled, for just 37, the afternoon after the incident.

In 1944 Constantine launched his own legal career by starting a long and tortuous series of examinations which finally resulted in his being called to the bar ten years later. After the war he continued to play league cricket professionally for a time and he also became a successful broadcaster. One BBC internal memorandum described him as having an ….excellent voice, sincere and unaffected. He is very intelligent and co-operative. He did however lack an eye for detail, and was given to make factual errors, once causing legal problems for the BBC when discussing his famous victory in the courts, by forgetting the name of the Defendant to the case and mistakenly naming another hotel chain.

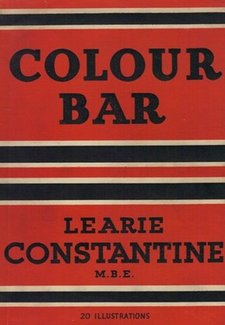

The demands of legal training, while maintaining his broadcasting and cricketing committments would have been far too much for many, but not for Constantine who found the time and energy to also serve on a Colonial Office Advisory Committee on racial matters, and he also wrote a landmark treatise on the subject, Colour Bar, that was published in 1954. The book began with the passage I quote in my opening. One reviewer described it as being written by one who is suffering from an open wound, inflicted upon an obviously likeable and sincere man by the petty insults and injuries which coloured flesh is heir to at the hands of thoughtless, prejudiced and ill-mannered white people It is as powerful book as any written on a subject which, despite much progress, to this day remains a blight on some societies. In the book Constantine mentions cricket just twice, once to briefly explain the Imperial Hotel incident, and once to explain how moves to have him sign for Lancashire after Ted McDonald retired in 1931 were blocked on account of his colour. That the author regarded the subject matter of his work as being infinitely more important than his own life is best illustrated by the space devoted to those issues. Colour Bar runs to 193 pages of, in the style of the times, closely typed prose – it must be 100,000 words. The hotel incident consumes four paragraphs, the Lancashire one just four sentences.

By 1954 Constantine was 52. He had lived in England for a quarter of a century and he himself was as fully accepted in white society as it was possible at that time for a black person to be. He was a man whose integrity, intelligence and newly acquired professional qualification would ensure he was financially comfortable and secure for life. Despite this he chose to return to Trinidad where, initially, he accepted a job as legal adviser to an oil company. He announced in one of his broadcasts; I owe my country an effort, I owe something to them, coming back there and trying to teach them what I have learned.

The job was not a complete success for Constantine. He struggled to integrate fully with the other senior executives (all white) at the company, yet at the same time the long years away meant that he did not always feel as comfortable with other native Trinidadians as he might have liked. Within a couple of years he was seriously contemplating an offer to take up a career at the Ghanaian bar, but eventually was persuaded, not without misgivings, to enter politics. Elected to Parliament as a member of the new People’s National Movement Constantine became Minister of Communications, Works and Utilities. He was not entirely suited to politics, probably being a little too sensitive and not sufficiently arrogant, and in 1961 he was about to return to the law, when he was invited to become Trinidad’s first High Commissioner to London.

Constantine’s fame meant that he was an ideal choice as High Commissioner in many ways, but his tenure in the position ended unhappily in 1964 after just one term of office, amidst a falling out with the People’s National Movement. The cause was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a tendency to wear his heart on his sleeve when faced with the ugly spectre of discrimination. In 1963 there was a strike at the Bristol Bus Company over its refusal to allow coloured staff to be drivers or conductors. Constantine travelled to the city, ostensibly to watch Frank Worrell’s touring West Indies side play Gloucestershire, but he involved himself in the dispute and largely through his efforts it was satisfactorily resolved. What Constantine did not do was inform his government of what he proposed to do and despite his success, and the episode was in large measure responsible for the Race Relations Act of 1965 coming into being, it was not the role of High Commissioners to involve themselves in the domestic affairs of the countries in which they were based.

Sadly Constantine’s health in his later years was not particularly robust and that started to curtail his activities, although he still did more than most men his age. He stayed in London and took up two positions those being a governorship at the BBC, and another as one of the three members of the original Race Relations Board that was set up under the 1965 Act. He also did some broadcasting and, finally, joined the Chambers of Sir Dingle Foot at 2 Paper Buildings. He had not actually practised law before, and it cannot have been easy amidst his other obligations and his health problems to begin to do so at the age of 62, but by all accounts he dealt more than competently with the modest practice that he built up.

Constantine was honoured by the British Government on three occasions during his lifetime. The first was in 1947 when he was awarded the MBE for his war work. In January 1962 he was knighted and then finally in 1969 he was awarded a life peerage. He chose the title of Baron Constantine of Maraval in Trinidad and Nelson in the County Palatine of Lancaster and, entirely fittingly, even if in many ways it was a sad reflection on 1960s Britain, he became the first black** man to sit in the House of Lords. It is unfortunate that his health prevented him from making more than one speech, as he would have got the appointment sooner had it not been blocked by Trinidad. It was not, it would seem, a personal issue but one related to the availability of honours generally to Trinidadians. The one speech he did make was in relation to the proposal that Britain should join the European Community or, as it was known then, The Common Market. The new Baron’s concern, unsurprisingly, was the potential effect on the country’s trading relationships with it’s newly independent former colonies.

On 1 July 1971, aged 68, Learie Constantine died at his home in London. He had been weakened by years of bronchial problems and eventually succumbed to a heart attack. In some ways he was a little isloated, and somewhat betwixt and between. He was comfortable in Britain, and was accepted and happy here, but he wasn’t British, he was Trinidadian. But his very public acceptance here did get in the way of his being fully embraced in the country of his birth. However no one doubted his greatness as a man and in death that was fully recognised. His body was flown to Trinidad and the arrival heralded with a guard of honour and a 19 gun salute. On 8 July he was buried amidst all the ceremony of a State Funeral. Two weeks later there was a memorial service in London, held at Westminster Abbey.

When I was a boy the name of Learie Constantine was one to be in awe of, such were his achievements both within and outside the game, although largely in those days the latter. Rather ironically forty years on and what is now remembered when his name is mentioned are his cricketing achievements, but there is an awful lot more to his story than three days at Lord’s in June 1928, and bowling bodyline at Douglas Jardine five years later.

*The title that Constantine wanted for Colour Bar, but which his publishers would not permit him to use.

**But not, to use an antiquated expression, the first man of colour – In 1919 Sir Satyendra Prasanna Sinha, a member of the Viceroy’s Council in India, had been given a Baronage.

You rarely miss if ever, Martin, but this piece is one of your finest, a real tour de force.

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am GMT 10 November 2012