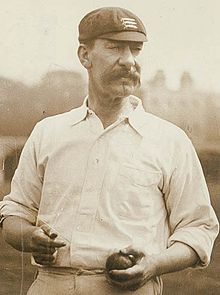

Alberto

Martin Chandler |

Few, whatever sport they follow, are able to resist comparing players from different generations. In many ways the attempts are meaningless, but no less interesting for that. In cricket, where such importance is attached to statistics the problem is, if anything, even more intractable. But such is the pleasure these debates give that they will doubtless continue as long as human beings duel with bats and balls across a distance of 22 yards.

Some statistics are a better yardstick of quality than others. Simple totals, given the relatively small number of First Class matches played in the modern era, are meaningless. Even averages, and the ability they give to make reasonable comparisons between peers, do not help much with cross generational discussions. Occasionally however there are records which permit simple and straightforward comparisons down the years. One of those is held by Albert Trott. The record in question is that he is the only batsman to have struck a ball clean over the pavilion at Lord’s.

The game in question was between the MCC and the Australians in July 1899. Trott was batting with the great Ranjitsinhji. He played himself in calmly enough, but then started hitting the ball very hard indeed. A sighter went into the seats at the top of the pavilion before, from the medium pace of Australian captain Monty Noble, he cleared the roof. The present pavilion has been at Lord’s since 1890. The old one had been cleared several times, most notably by WG Grace and the renowned hitter Charles Thornton, but Trott’s feat remains unequalled. As someone who likes to champion the cause of the the ancients of the game it is a matter of some comfort to me that however much fitness standards have improved in the last 117 years, and the technology of bat manufacturing, Trott continues to stand alone.

One irony of the famous hit is that Trott did not even get six for it, only four. The ball struck a chimney before ending up in a garden at the rear of the pavilion. It would have had to have left Lord’s completely to have counted as six in those days. There have, of course, been other big hits at the home of the game. ‘Big’ Jim Smith cleared the old grandstand on one occasion in the 1930s, said by some to be a bigger hit than Trott’s in absolute terms, but that stand is gone now, so the feat can no longer be a challenge to modern players.

I first became conscious of Trott’s record back in 1977 when watching that year’s Gillette Cup final on television. Glamorgan were playing Middlesex and a chunky middle order batsman, Mike Llewellyn, was putting bat to ball for the Welshmen. First he hit Mike Gatting, a man of very similar build, for six, and then repeated the dose to the off spin of John Emburey and deposited the ball into the gutter on the top tier of the pavilion. There followed a flurry of conversation between the commentary team about Trott’s record.

I first became conscious of Trott’s record back in 1977 when watching that year’s Gillette Cup final on television. Glamorgan were playing Middlesex and a chunky middle order batsman, Mike Llewellyn, was putting bat to ball for the Welshmen. First he hit Mike Gatting, a man of very similar build, for six, and then repeated the dose to the off spin of John Emburey and deposited the ball into the gutter on the top tier of the pavilion. There followed a flurry of conversation between the commentary team about Trott’s record.

In the 1920s there was, apparently, an occasion when Middlesex and England captain Frank Mann, whose son George was also destined to do both jobs, hit a straight drive so cleanly that it was still rising when it struck the brickwork behind the top row of seating. More recently that mightiest of smiters of a cricket ball, West Indian T20 specialist Kieron Pollard, has come close to emulating Trott, but still no one ever has and, ultimately, what is needed to do so today remains exactly the same as in 1899.

In the 1990s the sadly now defunct Cricket Lore magazine offered a cash prize of £5,000 to anyone who could match Trott. It wasn’t a life changing sum, but still a worthwhile one, and it certainly raised the profile of the record and indeed that of Trott, certainly one of the more interesting if ultimately tragic figures in the history of the game.

First and foremost Trott was a magnificent all-round cricketer. For Australia in Tests he averages the small matter of 102.50, better than Bradman or anyone else. That particular stat tends to be forgotten because as well as his miserly allocation of just three Tests for the country of his birth, he is one of the eclectic band of 14 who have played Test cricket for two countries, and his two matches for England reduced his overall batting average to a mortal 38.00. With the ball he must have been similar to the great Sydney Barnes, moving the ball both ways in the air and off the pitch at anything between the slow side of medium pace to genuine fast medium. In the field he was about a hundred years ahead of his time as he perfected the sliding stop in the outfield. The T20 age would have suited ‘Alberto’.

By the time he was twenty Trott was a professional cricketer in Melbourne. Brother Harry, his senior by six years was already an established Test player with eleven caps dating back to 1888. In 1894/95 Andrew Stoddart’s England tourists arrived for a tour that included the first five Test series. A century later David Frith wrote an account of the tour that he sub-titled The First Great Test Series. It was an entirely appropriate description.

In the two previous seasons Trott had played three First Class matches for Victoria. Very much a lower order batsman at that stage he had made no mark with the bat, but had set out his credentials as a bowler by taking eleven Tasmanian wickets. He had however found the going much tougher in his sole Sheffield Shield outing against South Australia.

The story is that after that debut Shield appearance Trott honed his skills by bowling at a cardboard cut out of the South Australian captain, the mighty all-rounder George Giffen. If true it certainly worked as in his first appearance against the tourists for Victoria Trott had figures of 6-103 and 2-110. With major changes expected for the Test side Trott had, despite his limited experience, put himself firmly forward as a genuine candidate for a Test place.

The first Test of the series, for which the Australian team contained only one Trott, Harry, was a remarkable one. England won after following on, a feat which would not be achieved again until the heroics of Ian Botham and Bob Willis at Headingley in 1981. The second Test was far from predictable as well. Giffen invited England to bat first after winning the toss and Stoddy’s men were then shot out for just 75. Despite that they still ran out winners in the end by 94 runs to move into a 2-0 lead.

Changes were made for the third Test and in came Trott for his debut. This time Giffen chose to bat on winning the toss, although at 157-9 he must have been ruing the decision. With Sydney Calloway Trott then went some way towards sparing his captain’s blushes as the last wicket partnership added 81 at better than a run a minute before Callaway was out for 41, leaving Trott unbeaten on 38.

If Trott was looking forward to impressing with the ball he was to be disappointed. He was given the new ball, but only for three overs. After he gave way to Giffen the captain and Callaway then bowled unchanged through a disappointing reply of just 124. With a lead of 114 Giffen would not have been anything like as unhappy when Trott went to the wicket with the score at 283-8 as he had been in the first innings but, in a timeless Test there might still have been a few concerns. If there were Trott soon dispelled them and when, ninety minutes later, Callaway was again the last man out Trott was on 72 and the lead 525. Harry Trott is quoted as asking who would have thought the kid could do it?

After what happened in the England first innings it would have come as no surprise to Trott that he was not given the new ball as Giffen and Calloway opened up. To begin with Archie MacLaren and Albert Ward looked fairly secure, but everything changed after Giffen replaced Callaway with Trott. Almost straight away the debutant claimed both openers and over his 27 over spell he took 8-43* as the game was quickly taken away from England. He might have had nine had Giffen not finally given him a break, after which the captain himself took the last wicket. Australia were back in the series.

The home side won the fourth Test by an innings and 147. After winning the toss Stoddart asked Australia to bat in difficult conditions. The decision looked a good one as six wickets fell for 51, but the wicket was easing and the lower order mounted a recovery. When the last man Charlie ‘Terror’ Turner was dismissed the final total was 284. Trott was unbeaten on 85 this time. The weather turned again and the second day was washed out. On the third day, with the wicket now a treacherous one, England folded for 65 and 72. This was no thanks to Trott though, who was not called upon to bowl so much as a single delivery.

The fifth and deciding Test served only to reinforce the status of the series. England won the match by successfully chasing down 298, at that point the highest fourth innings total to win a Test match. They did so in style as well, by six wickets, Yorkshireman John Brown contributing one of the great Ashes centuries, his 140 being his only three figure score in an eight Test career. After his efforts in the previous Tests Trott was disappointing, being dismissed for 10 and 0. His bowling figures were 1-84 and 0-56.

It seemed inevitable that when the Australian side to tour England in 1896 was chosen that Trott would be in it. He began the 1895/96 season well, taking wickets against New South Wales. After that it is fair to say he struggled, but ordinarily his form in the 1894/95 series would surely have justified his selection. In the event only one Trott, Harry, subsequently elected as captain by the rest of the side, was picked.

The squad selected comprised only fourteen players and there were many who queried the younger Trott’s omission. It might, had there not been other controversies, have been the case that a groundswell of public opinion might have gathered behind the young all-rounder. He might have had more support from his brother. Harry wasn’t a selector, but was after selection a member of the tour committee and certainly Albert himself seems to have felt Harry could have done more. When Trott announced that he would, at his own expense, be travelling with the party to England in order to seek work as a professional in England it was announced that he would be looked on as cover for the party. He was never called on however, and other than one occasion in 1896 when their paths crossed and they briefly acknowledged each other there is no evidence the two brothers had any further dealings with each other.

For Trott that 1896 summer was spent qualifying for Middlesex. He was unable to play in the Championship but could turn out for the MCC and for any scratch side that wanted to select him. Otherwise he spent his time bowling at the MCC members in the nets. He played a number of First Class matches, enjoying modest success with bat and ball. Some doubt was expressed as to the fact that he seemed not yet to have decided how he wanted to bowl such was the variety of styles in which he dabbled.

There was a trip back to Australia in 1896/97 when Trott married and then returned to England with his bride. His bowling was much more effective in 1897 and then in 1898 he was finally able to play in the Championship. He managed to miss the whole of June with a hand injury, and made a slow start on his return, but he ended up with 130 wickets at 17.94 to general acclaim. That winter he travelled to South Africa with a side skippered by Lord Hawke and he proved most adept on the matting wickets and he played twice for England. He scored just 23 runs in his four innings but 17 wickets at 11.64 showed just how difficult he was to play.

With the bat Trott scored his first First Class century in South Africa. A decade after Trott’s death his captain, Hawke, published an autobiography. His opinion of Trott was that he was apt to take batting lightly. Indeed, towards the end he degraded his magnificent hitting powers in blind swiping. Alas, he was one of those who through too short a life could not resist temptation. A wit once said “it is not temptation if you resist it”. Alberto resisted none. Hawke added an important rider however, at one time he was the best all-round cricketer in the world.

The two seasons of 1899 and 1900 saw Trott at the peak of his powers. In both he did the rare double of 1,000 runs and 200 wickets and there were many personal highlights. Where he generally disappointed however was against the Australians, who he must have been desperately keen to do well against, and for the Players against the Gentlemen, in those days a fixture regarded as every bit as important as any Test match. The problem seems to have been simply that he tried too hard, and was anything but adept at working out how to dismiss the best batsmen. A frequently quoted remark is an observation directed at Trott by his Middlesex teammate Gregor MacGregor; Albert, you would be the greatest bowler in the world if you had a head instead of a turnip.

Unfortunately Trott had peaked in those final summers of Victoria’s reign. He continued to play until 1909, and held his place in the Middlesex side throughout, but the peaks were neither quite so high or frequent as in his great days. In 1907 he took his benefit, and he certainly had one of his better days in that match. The myth has grown up that he effectively sabotaged his own benefit by taking 7-20 in the Somerset second innings, including the unique achievement of four wickets in four deliveries and a separate hat trick. Given however that the feats were achieved on the third day of the match, so money had already been taken at the gate from spectators with every reason to expect a full day’s play, there is no logical basis for the assertion.

The inconsistency of Trott in his later years is best illustrated by the fact that in 1907 a third of his wickets came in just three matches. In 1909 he played regularly but his returns were well down on a decade before, with just 573 runs and 42 wickets. In 1910 he simply couldn’t hold down a place in the side, and appeared just five times in the First Class game. He was 37, no great age in an era when many played with success well into their forties.

There is no doubt that as he aged Trott did not do as much as he might have to retain his fitness. He always enjoyed a drink, and as the years passed he put on a good deal of weight. The suppleness of youth was an important factor in the way Trott played the game, and was what made his quicker ball so dangerous. Without the ability to whip that one through them batsmen had less to fear.

Life began to unravel for Trott as his career wound up. He became an umpire in the end, and seems to have been adequate at that but in 1910 his marriage ended. His wife took their two daughters back to Australia and Trott never saw his family again. Mrs Trott did well to put up with her husband for as long as she did. As well as the twin evils of drinking and gambling Trott was inclined to stray. One particular lady in Taunton of whom Trott was a client was murdered and he was interviewed by police, although there was never any suggestion he was responsible for her death. When she got back to Australia Trott’s wife and children kept well away from Trott’s surviving family and his biographer was able to ascertain only the most basic information about what happened to them.

As for Trott he suffered increasingly from dropsy, the condition that caused his bloated appearance. In 1914 the associated discomfort meant that he was no longer able to stand for long periods thus preventing him from continuing with his umpiring. His only real source of income denied him it is hardly surprising Trott became depressed. In July 1914 he was admitted to hospital, but then discharged himself and returned home to his lodgings. He asked his landlady to get him a sleeping draught. Based on what happened next one is left to suspect that was eyeing a clean exit. If so he was thwarted by the local chemist who, quite properly, refused to supply it without a prescription.

Trott was much distressed by the unavailability of the draught, and shortly afterwards he was told it had proved unobtainable his landlady heard a shot from his room. She hastened to Trott’s assistance but he was beyond help. A handwritten will was found on him in which he left his estate, less an album of photographs he left to a friend in Australia, to the landlady. That estate amounted to just £4. There was a post mortem that came to the conclusion that Trott had taken his own life whilst of unsound mind. There was no explanation of how he came to own a firearm.

Due to Trott’s parlous financial state the MCC paid for the funeral, although they did not stretch to a headstone. That was added many years later at the expense of the Middlesex county club. It describes Trott in simple terms; A Great Cricketer. His demise was a genuine tragedy, but did not linger long in the headlines. Five days after Trott’s death the war to end all wars begun. Tragedy suddenly became commonplace, and the memory of Albert Trott soon began to fade.

*You can read more on Trott’s 8-34 in Supreme Bowling, the sequel to Masterly Batting, published last week by Von Krumm Publishing

I remember Clive Radley was reported as almost achieving the feat in the late 70’s but again not quite. When I read about it it was the first time I had heard of AT.

Comment by paul mullarkey | 8:44pm BST 14 October 2016