A conspiracy or not a conspiracy ?

Martin Chandler |

Saturday December 7th 1963 was the second day of the first Test match between Australia and South Africa at the Gabba in Brisbane. Australia’s captain was Richie Benaud and while he would play in the final three Tests of the series as well this was to be his last as captain. The Australian team had been selected by a committee that comprised former captains Sir Donald Bradman and Jack Ryder, as well as Dudley Seddon who had played briefly for New South Wales in the late 1920’s.

The great all rounder, Alan Davidson, had retired at the end of the Ashes series in 1962/63 and Australia were looking for another left arm pace bowler to take his place. The selectors’ attention was drawn to Ian Meckiff who had last played Test cricket, without a great deal of success, in the series against the West Indies in 1960/61 and who had, since then, been struggling to rebuild his career following injury. Meckiff had enjoyed an excellent season in Shield cricket in 1962/63 and had taken eleven good wickets in the two Shield matches that preceded the Test.

In their first innings Australia were all out for 435 due, in large part, to a fine innings of 169 by former Olympic hockey player Brian Booth. South Africa, who were ultimately able to comfortably draw the match, faced their first over from Garth McKenzie before Meckiff took the new ball from the other end. Meckiff’s opening over was the final one of his First Class career as square leg umpire Col Egar no balled the second, third, fifth and ninth deliveries. On five previous occasions Egar had stood in a First Class match in which Meckiff played without, apparently, any concern over his action. Similarly Egar’s colleague, Lou Rowan, had umpired Meckiff before without incident.

Meckiff was a popular figure and the vast majority of the Gabba crowd were horrified at his treatment. The atmosphere simmered all day and half an hour before the close of play it was necessary for the umpires to suspend play for two minutes amidst the crowd’s deafening chants of ‘We want Meckiff’. When the close finally came a large number of spectators invaded the playing area and raced towards the players, grabbing Meckiff and carrying him shoulder high to the pavilion. Having safely delivered Meckiff to the dressing room the crowd then turned their attention to the unfortunate Egar who was booed mercilessly as he left the ground. Those present had witnessed what was probably the most controversial day in Test cricket since the events of 31 years previously when Harold Larwood had injured Bill Woodfall and Bert Oldfield in the third Test of the Bodyline Series.

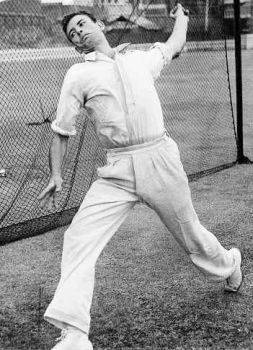

Meckiff was just 28 when his career came to an end. He had played in 18 Test matches and taken 45 wickets at 31 runs apiece. He was a genuinely quick left arm bowler with an unorthodox front on bowling action. He had made his Test debut in South Africa back in 1957/58 but had come to prominence in the course of Australia’s 4-0 victory in the Ashes Series of 1958/59. In the second Test of that series his six for 38 in the England second innings dismissed the visitors for 87 and in the four matches in which he played Meckiff had taken 17 wickets at only 17 apiece.

England had won the Ashes in 1953 and retained them comfortably in the next two series. They had been widely expected to do well again in 1958/59 against an Australian side that was in transition. The tour was an unhappy one for England, there being selection issues before it started, and the Australian bowling attack aroused great controversy. Meckiff was condemned as a thrower as were fellow pace bowlers Gordon Rorke and Keith Slater, who played, respectively, in two and one of the Tests, as well as batsmen Jim Burke who was an occasional off spinner and who bowled in two matches.

The accusations of unfair bowling were not, however, just sour grapes on the part of the English as many Australia commentators agreed that Meckiff’s action broke the laws of the game and there had been murmurings throughout his career despite the fact that he had, at that point, never been no balled.

In the following season Meckiff toured India and Pakistan without, so it would seem, any difficulty and he played in two Tests in the 1960/61 series against the West Indies, including the tied Test, when he was the last man out, but his season was badly disrupted by injury and he was left out of the 1961 touring party to England. The conspiracy theorists inevitably suggested that the reason for Meckiff’s omission was to avoid a confrontation with the hard line English umpires who had ended the career of the South African, Geoff Griffin, in the previous summer, and was not therefore related to his injury problems or the wholly justified claims for selection of Ron Gaunt and Frank Misson who, in the event, took the last two pace bowling places.

Whatever the reasons for Meckiff’s omission from Benaud’s touring party he came back strongly in domestic cricket in 1961/62 and, as noted, the more so in 1962/63 when he took 58 wickets at less than 20 apiece. More ominously however he was, for the first time in his career, no balled on two separate occasions in that season with, on each occasion, just a single delivery being adjudged to have broken the law.

The photograph of Meckiff’s action which generally appears in books where this episode is dealt with shows a man with his bowling arm demonstrably bent at the elbow and, as already indicated, his action was criticised by many throughout his career. That said, as has always been known, photographs can be deceptive and there is a much less frequently published sequence of stills which appear to show Meckiff with a perfectly fair action. Those stills, not surprisingly, appear in Meckiff’s 1961 autobiography but rarely see the light of day anywhere else. Meckiff himself always maintained that he was incapable of fully straightening his left arm and that that idiosyncrasy, coupled with the flick of his unusually slim wrist, which was an integral part of his action, was what gave to some the appearance of unfairness.

At the beginning of the 1963/64 season the Australian Board had declared an intention to deal strongly with the issue of unfair bowling which, at that stage, was seen as the game’s greatest problem. The state associations were directed not to select bowlers with dubious actions, but the Victorian selectors chose Meckiff nonetheless. It may well be significant that the two First Class matches played by Meckiff before the first Test were at home, and that accordingly the umpires were Victorians.

Those who believe that Meckiff was set up as a sacrificial lamb also point to Benaud’s conduct of the match. It is suggested that his failure to try and put Meckiff on at the other end, and more generally in not giving him even a single further over are indicative of the fact that the selectors, the umpires and Benaud all knew exactly what was going to happen. Some support the argument further by pointing to the team selected containing five frontline bowlers. It was not unheard of, but was most unusual, for Benaud to bat as high as six, and that, so it was said, was evidence of the expectation that an extra bowler would be required.

One matter which it ought to be stressed is not significant is the fact of the Test match being Benaud’s last as captain. He had intended to retire at the end of the series in any event but between the first and second Tests he broke a finger and was unable to take his place again until the third Test. Bobby Simpson had been groomed as Benaud’s successor anyway and he, having led the Australians to victory in the game Benaud missed, was understandably left in charge following Benaud’s return for his last three caps.

Those concerned have, not unexpectedly, always denied that there was any plan to put forward Meckiff as a sacrifice although their statements are sometimes less than convincing. In particular writers have seized upon a comment made by Egar to Meckiff afterwards, by way of apology, that ‘it had to be done’ as being indicative of there being a directive from on high rather than the alternative interpretation that Egar felt unable to allow the law being broken to go unpunished. Egar did, of course, stand by the latter scenario but one thing upon which all observers are consistent is that there was, over the duration of his career, no significant change in Meckiff’s action and, as indicated, Egar had allowed him to bowl unhindered in the past.

The saddest aspect of the case, and one which the Brisbane crowd no doubt were acutely conscious of, was the effect of the controversy on Meckiff himself. A volume of autobiography, ‘Thrown Out’, had been published in 1961 and set out clearly the distress that all the arguments over his action had caused, not only to Meckiff himself, but to his family and those close to him as well. In addition he was universally recognised throughout the game as a thoroughly decent and likeable man and he was without doubt the long term victim of the events of 7 December 1963.

After Meckiff left the game he moved into advertising and subsequently also worked as a cricket commentator. Up until his retirement he was a senior executive with a company called Boyer Sports Media and remained, in that capacity, involved in the game although he was to never play the game again at any level. The depth to which Meckiff was hurt by the controversy is perhaps best illustrated by his actions when the issue came back to haunt him again in 1966, when Simpson published a book called ‘Captain’s Story’, in which he criticised various fellow players with Meckiff chief amongst them. The controversy about the book was such that it quickly had to be withdrawn from publication in its original form but a libel case followed which Meckiff pursued diligently for as long as five years before receiving an out of court settlement and a full apology. The outcome of the litigation was hardly surprising. The relevant chapter went far beyond legitimate criticism and Simpson and/or his ghost, remarkably, felt able to set out as fact that Meckiff had deliberately and cynically set out to flaunt the laws of the game.

The question remains then as to whether the events of that Saturday in December 1963 were part of a plan, carefully hatched, to demonstrate that Australia was taking the lead in ridding the game of the curse of unfair bowling. The accusation was that the Australian Board, their selectors, their captain and their umpires had conspired to achieve this and that Ian Meckiff was the man who would pay the price.

As far as the Board are concerned it was they who had issued the directive designed to stamp out unfair bowling, an initiative championed by Clem Jones. Jones had also sought without success, as the Board’s minutes make clear, to ensure that Meckiff would not be selected for the first Test. In the circumstances it seems unlikely, given their lack of unanimity, that the board could have been involved in any sort of conspiracy.

Once the dust settled the selectors came in for much criticism and no doubt Bradman’s firm but monosyllabic denial of any plan, coupled with his consistent refusal to discuss the issue in any detail, did nothing to dampen speculation. Bradman and his fellow selectors were in a difficult situation. Bradman alone of those involved had been in England in 1960 and witnessed at first hand, and from an excellent vantage point, the end of Geoff Griffin’s career. He knew beyond a shadow of doubt that were Meckiff to tour England in 1964 that he would suffer the same fate as Griffin and that cricket, and Australian cricket particularly, would be the loser. On the other hand current form fully justified, and, for Victorians at least demanded, Meckiff’s recall. Meckiff’s popularity should not be ignored. Bradman may well have felt that if, as appeared likely, Meckiff had enjoyed another superb season without selection against South Africa and was then left out of the 1964 tour, that the effect of that chain of events would be more damaging than Meckiff being selected when he was.

Richie Benaud has published his thoughts widely since leaving the game although he has said comparatively little about Meckiff. For Benaud the analysis is simple. He was the captain of the Test team and obliged to work with the players he was given and do his best to secure victory for Australia. After two overs of their first innings South Africa had scored 25 runs and Meckiff, understandably in the circumstances, had bowled appallingly. It would have been very easy for Benaud to have appeased the anger of the crowd, insofar as it was aimed at him, and give Meckiff the ball from the other end to try again, but it would not have helped Australia. In any event one thing Benaud has always maintained is that, influenced no doubt by the Board’s pre-season directive, he had made the policy decision that any bowler who was called for throwing on his watch would immediately be removed from the attack and not called upon again.

Turning to the umpires neither has ever gone into print and said anything to suggest there was any direction given to them to no ball Meckiff. Rowan did, in due course, publish an autobiography but those who seek a definitive answer will find nothing in there. The umpires would, as servants of the Board, have known of the Clem Jones inspired directive and perhaps that made them decide that they could no longer give Meckiff the benefit of the doubt. Clem Jones said, many years later, that he knew for a fact that Bradman had instructed the umpires to call Meckiff but he was unable or unwilling to say how he knew. Of course had there been pressure, improper or otherwise, brought to bear on the umpires then the man best placed to exert that pressure would have been the man who, in his capacity as Chairman of the Umpire Selection Committee, could control their future. From Clem Jones comments it might reasonably be supposed that Chairman was Sir Donald Bradman ………….. in fact it was none other than Alderman Clem Jones himself!

In this writer’s opinion the only reason that there is a conspiracy theory at all is because the Board, the selectors, Benaud and the umpires did not bother to meet in advance of the selector’s decision in order to resolve an issue which, it must have been obvious to all, was going to cause controversy one way or another before the season was out. Adding to that failure the shabby treatment of a genuinely popular sportsman, and the loose cannon that was the good Alderman, and it is hardly surprising that a very straightforward set of facts were manipulated in various ways in the weeks, months and years that followed.

It was to be more than thirty years before the issue of unfair bowling actions started to become a hot topic again. Ian Meckiff, now 74 years of age, is enjoying a happy and peaceful retirement without controversy, and he has, no doubt wisely, kept his own counsel, in public at least. It would however be interesting to know his thoughts on the subject in the light of Cricket Australia’s recent pronouncements regarding the doosra, and to imagine how his career, and those of others, might have unfolded had the powers that be decided, then as now, not to banish but to change the way the laws of the game were interpreted in order to accommodate them.

Genuinely fascinating and well-written piece. Its author presents the facts and records the public pronouncements by the various parties involved as they are and allows them to speak for themselves before finally offering his own thoughts. Doesn’t indulge in the kind of psychological speculation that afflicts so much sports writing nowadays.

Hope CW will revisit interesting topics of the past more often. 🙂

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am BST 6 September 2009

Yep great piece fred.

Comment by zaremba | 12:00am BST 6 September 2009

Really interesting bit of writing there, fred.

Comment by Uppercut | 12:00am BST 6 September 2009

It has always been an interesting case, with plenty of circumstantial evidence for the conspiracy theorists.

I was hopeful that when the Don passed on further evidence would come to light but nothing definitive has been said still.

Meckiff has made a comment about the 15 degree rule, saying there would not have been a fuss.

Comment by Midwinter | 12:00am BST 8 September 2009

Quality article – a great read. 🙂

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am BST 9 September 2009