9-86 And All That

Martin Chandler |

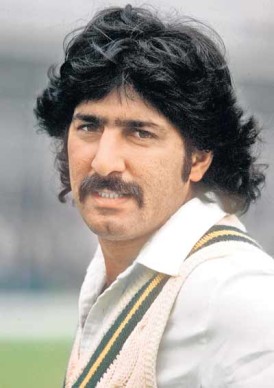

Years ago I met a former teammate of Sarfraz Nawaz, who described him as a man with many faults. The Pakistani pace bowler could be aggressive, contrary and defiant. In his playing career he was often quick to anger, and was certainly difficult to captain. But even my informant made the comments he did with a smile on his face, and for a cricket fan in the 1970s and 1980s it was difficult not to like the tall and handsome fast medium swing bowler who clearly did not want for either courage or self-confidence. He was after all the man who in 1975 at Northampton, when Jeff Thomson let him have a short one, proceeded to inform the fearsome Australian that there was a vacant plot for him in a local cemetery. Sarfraz hung in there to score 26 and 31 and, when it was his turn to bowl, unleashed a bouncer that saw the back of Thommo for just four.

Sarfraz’ reputation now is as the man who introduced the dark art of reverse swing to the game, something which confirms that whatever faults he had as a player he was nobody’s fool. As a bowler he had a unique approach to the wicket, carrying himself at near enough bolt upright. No one ever tried to coach that out of him, and as a youngster he was called ‘steel spine’.

In the late 1960s Pakistan’s pace bowling stocks were, to put it kindly, moderate. They blooded Salim Altaf in England in 1967, and he went on to play 21 Tests without ever really breaking through, a career haul of 46 wickets at 37.17 being testament to that. Also in England in 1967 was Niaz Ahmed, but his career was to consist of just two matches. In the first Test of the return series in 1968/69 Asif Masood made his debut. Living proof that statistics don’t always tell the truth Asif, whose unorthodox action was brilliantly likened by John Arlott to Groucho Marx chasing a pretty waitress, took 38 wickets at 41.16 in his 16 Tests. He was a much better bowler than those numbers suggest.

Two of Pakistan’s best batsman, Majid Khan and Asif Iqbal, took turns with the new ball in that 1968/69 series without conspicuous success. Prior to back problems causing him to concentrate on his batting Asif had been a useful seamer, but Majid was never anything other than a part time bowler. Despite that when, for the third Test, the 20 year old Sarfraz was handed a debut after taking 14 wickets in five First Class matches at a relatively ordinary 33.79, the new ball still went to Majid. In a game cut short by the crowd riot that led to a hurried flight home for the Englishmen Sarfraz took 0-78.

An unremarkable performance on a docile pitch did not however matter much for Sarfraz as his lucky break had come earlier on the tour when a member of the England party, the Northamptonshire opening batsman Roger Prideaux, had been impressed by what he saw of the young Pakistani in the nets. Prideaux was sufficiently keen to see more to extract an invitation from his county for a year’s trial. It must have been a rude awakening for Sarfraz. He spoke no English and whilst his fellow Pakistani, Mushtaq Mohammad, was also at the club he was with the first team. Nonetheless Sarfraz must have knuckled down as he had an excellent season with the seconds, and in the game against the touring West Indians, when he could play for the first team, he picked up five wickets.

In 1970, his first year of availability for Championship matches, Sarfraz took 63 wickets at 29.22 and was described in Wisden as having a useful season. In 1971 however he had a miserable time. His domestic season was successful enough as he earned a place in the party that toured England in the first half of the 1971 summer. In the event however injury restricted his availability, and he only started three matches in which he took 2-219. It was little better back at Northampton for the second half of the season and 10 wickets at 37.70 in six matches were not enough to earn him another contract. There was also controversy about the cause of his troubles. For Sarfraz it was a back problem, although the Pakistani management indicated that expert reports suggested the issues were psychological rather than physical.

Without a county contract in 1972 Sarfraz joined Nelson in the Lancashire League. He had a fine all round summer, much improving the fortunes of a club that had spent a number of years in the League’s lower reaches. The club were happy to have him back in 1973, after a winter in which he had become a Test player once more, but Nelson slipped back that year. Sarfraz’ bowling was rather less effective, although he scored plenty of runs and did enough to cause Northamptonshire to conclude that perhaps they had made a mistake by letting him go, and he was invited back to the county in 1974.

In between his two stints in Lancashire Sarfraz had toured Australia. Pakistan had left him out for the first Test, which they lost by an innings and plenty. With Sarfraz taking his first Test wickets in the second Test the losing margin was 92 runs and whilst the Australians completed a clean sweep at the SCG the Pakistanis had only themselves to blame for their defeat as they failed to reach a fourth innings target of 159. Sarfraz had taken 4-53 and 4-56 and along with Salim earned the respect of Ian Chappell who wrote that they; made the ball swing, bounce and cut off the wicket and maintained an excellent line and length. Still not the finished article however Sarfraz disappointed in the three matches that followed in New Zealand and, on returning to Pakistan, took 1-156 in two Tests against England. In the second of those Sarfraz did at least have the consolation of having almost certainly saved the game for Pakistan. Coming in at 129-8 on the final day he kept out the English spinners for more than an hour and a half despite a clutch of close in fielders. With his powerful shoulders Sarfraz was always a good bet for a few quick runs, but his unbeaten 33 on this occasion showed he could defend as well.

For most of 1974 Sarfraz was engaged with the Pakistan tourists, although for his county he achieved much more in just five matches than he had in 1971 in six. For Pakistan he played a significant part in a performance that saw all three Tests drawn and he might, had rain allowed the final day of the first match to start, have played a match winning role in a famous victory. First his 53 in Pakistan’s first innings helped them to a lead of 102, and then he took seven wickets as England closed the penultimate day with 44 still needed and four wickets to fall with only Keith Fletcher of the recognised batsmen left. The second match was again spoiled by rain and the third by a low slow batsman’s wicket at the Oval. So frustrated did Sarfraz become that at one point in the England innings he bowled a beamer at Tony Greig necessitating a swift intervention by umpire ‘Dicky’ Bird.

In 1975 Sarfraz again missed part of the county season, this time because of the first World Cup. He still managed to be one of only two bowlers in the country to take more than 100 wickets in a batsman’s year. He was scarcely less effective in the long hot summer of 1976, and in September of that year helped Northants to their first piece of silverware, the Gillette Cup. He was to remain with the county until 1982. His powers were certainly on the wane by then, but it was the attraction of the alternative of Kapil Dev that swayed the committee in favour of the Indian all-rounder. As on the last occasion Northants had rejected him Sarfraz signed for Nelson. To the annoyance of the club he didn’t turn up in Lancashire in 1983, a gig that former Surrey and England batsman Graham Roope was happy to take up in his place.

International scheduling was such that after their 1974 series in England Pakistan had just two Tests in the next two years, and then 11 in six months. At the start of that run in 1976/77 Sarfraz appeared for the first time with Imran Khan, and the pair took 27 wickets between them in three Tests against New Zealand. In Australia the first of three Tests was drawn and then, in Sarfraz’ absence through injury, the second was lost by 348 runs. Fit again for the third Test at the scene of their near success four years earlier Pakistan, thanks to Imran’s first great bowling performance (12-165), shared the series. Sarfraz chipped in with three good wickets in each innings to make a full contribution to Pakistan’s first win on Australian soil.

In 1977/78 Pakistan hosted England for three Tests. Sarfraz showed his unpredictable side, leaving Pakistan for England after the first Test because he was dissatisfied with his terms and conditions. It is to be assumed the Board must have accepted he had a point because a couple of weeks later he was back and in the side for the third Test. In a return series in England in the summer of 1978 Sarfraz again missed the second Test. This time he had pulled up lame in the first after just six overs. What followed next was a home series against India. Sarfraz took 17 wickets at 25.00 and was a major contributor to Pakistan’s two victories in a three match series.

In March of 1979 Pakistan played two Tests in Australia. This was towards the end of the World Series Cricket schism, but Australia were still without their Packer players and had just been on the wrong end of a 5-1 Ashes thrashing. Pakistan on the other hand, motivated no doubt in large part by a desire not to risk defeat by India, were picking their WSC men who, by now, included Sarfraz. The atmosphere in the Test was not going to be the best from the moment the Pakistan captain Asif Iqbal likened the Australian side to a bunch of schoolboys.

Pakistan won the first of the two Tests, thanks almost entirely to Sarfraz. Graham Yallop won the toss and asked Pakistan to bat. They were reduced to 122-7 before Sarfraz hung around long enough to score 35 out of the 74 added for the last three wickets. Later, with Australia on 305-3 chasing a victory target of 382 Sarfraz took the new ball, cut down his run and produced a devastating spell of swing bowling of 7-1 to end up with career best figures of 9-86, the first nine wicket innings haul for a Pakistan bowler and indeed at that time the best figures by a pace bowler in Test history. Other than Kim Hughes, who holed out trying to force the pace, no Pakistan fielder was involved in any of the dismissals.

The second Test in the series was an ill-tempered one and again Sarfraz was in the thick of things, albeit this time for very different reasons. In Pakistan’s second innings, after they appeared to be dead and buried, Asif produced a superb innings and what looked like being an Australian fourth innings target of little more than a hundred suddenly started to stretch and became 236. At that point pace bowler Alan Hurst decided to ‘mankad’ Pakistan’s number eleven, Sikander Bakht. Australia got the runs easily enough, but when the opening partnership reached 87 and Alan Hilditch picked up the ball to return it to Pakistan it was Sarfraz who immediately appealed, and Hilditch became only the second man in Test history to be dismissed handled the ball.

A six Test tour of India was next on Pakistan’s itinerary, but Sarfraz wasn’t selected. Skipper Asif Iqbal, whose last series it was to prove, told the selectors that if they chose Sarfraz they would have to choose a different captain. The series was lost 2-0 and for the visit of Australia that followed Pakistan had a new captain, Javed Miandad, so Sarfraz played, albeit with no success. He scored just 22 runs in the three Tests and took only two wickets.

In November 1980 Pakistan’s guests were West Indies. In the first Test Sarfraz, by putting on 168 for the seventh wicket with Imran, helped his side to a draw, but he was an unhappy man, declaring the pitch had been doctored to help Pakistan’s spinners. He proceeded to flounce off to London for, he said, treatment on a groin strain. Another reason for his departure was, apparently, his disappointment with Javed’s captaincy. He was back and playing again in the final Test of the series but despite bowling economically he picked up just a single wicket.

In Australia in 1981/82 Sarfraz renewed his acquaintance with the MCG and his bowling helped Pakistan to a consolation victory. Sarfraz’ most memorable contribution to the first two Tests was his top score of 26 in the first innings at the WACA which helped his side from 26-8 to the comparative respectability of 62 all out.

Unsurprisingly Sarfraz was one of the senior players who refused to play on under Javed’s captaincy in the 1981/82 series against Sri Lanka and he only returned to the fold for the northern hemisphere summer of 1982 when, for the first time, Imran was skipper. The series was won 2-1 by England, but Sarfraz played a role in the Pakistan win at Lord’s. Unfortunately however he was not fit enough to play in either of his side’s defeats in the other two Tests.

Back home in Pakistan in 1982/83 Sarfraz’ injury prevented him from playing any part in the 3-0 drubbing of Australia, but he was back to play in all six Tests against India. Left to their own devices the selectors would not have picked him, but Imran wanted him and eventually persuaded the Board President to overrule the selectors. Imran’s 40 wicket haul at a little over 13 runs apiece was the major reason for the home side’s 3-0 victory but, with 19 wickets, Sarfraz supported his captain well and fully justified the lengths Imran went to in order to get him in the side.

It was Imran’s turn to be injured when the Pakistan side to visit India in 1983/84 was chosen. Acting skipper Zaheer Abbas was no more of a Sarfraz enthusiast than Javed, and he didn’t try to dissuade the selectors from leaving Sarfraz out of the side. The method adopted was somewhat underhand. Sarfraz was never keen on nets or training, and became even less inclined as he got older. Those that knew him let him get on with it, as they understood he got into shape from bowling, but the Board decided all candidates for the tour had to pass a fitness Test. Sarfraz failed of course and, having talked of retirement before, most observers thought that at 33 years of age the Sarfraz show was over particularly when, after expressing his views about the selectors in the media, he was handed a six month ban.

The ban left Sarfraz unable to play in the five Test series in Australia that followed the trip to India or the three home Tests against England that rounded off Pakistan’s season. The problem the selectors had however was that as Imran remained unable to bowl their reserve pace bowling stocks, just about manageable in India, were woefully inadequate in Australia. The ban was therefore lifted and Sarfraz travelled to Pakistan half way through the tour and played in the final three Tests with some limited success. He did rather better against England and indeed in his final Test was to get as close as he ever got to a First Class century, scoring 90. It was an important innings too as he played the leading role in a 161 partnership with a lame Zaheer that would have paved the way for a Pakistan victory, had their middle order not thrown away a wonderful position in the fourth innings. In the end the lower middle order, so Sarfraz again, had to shut up shop to get the draw.

After his retirement Sarfraz did not mellow. In the 1987 World Cup Pakistan lost in the semi-final to Australia. An unimpressed Sarfraz suggested that the Pakistani players had accepted money to lose the game. Skipper Imran dismissed the reports following which Sarfraz became more specific, alleging a conspiracy between Javed Miandad and Abdur Rahman Bukhatir, the man largely responsible for the game taking off in Sharjah. Javed the batsman had held the Pakistan innings together and, following an injury to Salim Yousuf, had kept wicket capably through most of the Australian innings. Both Javed and Bukhatir sued Sarfraz for libel damages in Pakistan, and Bukhatir also did in the UAE. Neither case was ever resolved, Javed eventually calming down and losing interest in the case in Pakistan, and Sarfraz giving the UAE a swerve.

An expressed desire to keep the game clean later prompted Sarfraz to accuse Asif Iqbal of ‘irregularities’ in relation to the Indian tour of 1979/80, as well as succeeding generations of underperforming in the Texaco Trophy in 1992 and during a tour of South Africa and Zimbabwe in 1994/95. It was Sarfraz who made a sworn statement in Lahore to Mr Justice Qayyum in 1998 and suggested Dean Jones was forced to retire because of his involvement with match fixing. In 2007 Sarfraz was one of those who was quick to suggest that the tragic death of Pakistan coach Bob Woolmer was the responsibility of organised criminals from the world of gambling. As Sarfraz’ many critics were keen to point out he himself was a keen follower of the sport of kings, and no stranger to gambling emporia.

In 1993 Sarfraz crossed swords with the English criminal courts twice. In February of 1993 he appeared before Marylebone Magistrates Court and was fined £100 and disqualified from driving for 15 months for a drink/driving offence. At the time he was on bail for a much more serious offence. A dancer had accused Sarfraz of falsely imprisoning her and stealing money from her the previous year. It was October of 1993 before Sarfraz knew his fate on that one. His alleged victim failed to appear at the Old Bailey in order to tell her story and the charges against him were dismissed. It is one of the weaknesses of the English Criminal Justice system that such allegations, so easy to make and so difficult for an accused to throw off, should result in a Defendant being named before he or she is tried.

As Sarfraz left the Old Bailey without a stain on his character the false imprisonment charge is only of indirect relevance to his other appearance before a UK court at this time. That relevance is that his defence was publicly funded through legal aid, Sarfraz being in receipt of income support of just over £40 a week at the time. Despite that he was still able, during the fourteen months following 26 August 1992, to pursue a libel claim in the High Court, a hugely expensive legal forum and a type of claim for which legal aid is not and never has been available.

The background to the litigation arose out of the 1992 season, one of the more eventful English cricketing summers and by the end of which England had lost a five match Test series to Pakistan 2-1 The English batting suffered a number of collapses against spells of fast bowling from Waqar Younis and Wasim Akram that saw the old ball swinging prodigiously, and there was a groundswell of popular opinion that believed the Pakistanis, by interfering with the ball, were guilty of cheating.

In an article in the Daily Mirror Alan Lamb, who had played in a couple of the Tests and all the ODIs of the summer, wrote an article that accused the Pakistanis of deliberately damaging the ball. He concluded the article by explaining what was done and adding; it was an old trick first shown to me a dozen years ago by my old Northamptonshire teammate Sarfraz Nawaz. He was a genuine swing bowler, but he learnt the trick to help him bowl on the concrete hard surfaces in Pakistan.

The article was a damning indictment of the then current Pakistan side, but although Wasim and Waqar, through a solicitor, issued a statement on the subject, it was Sarfraz who, having decided he had been labelled a cheat, issued a libel writ. It would seem to be a reasonable assumption that some other individual or organisation was responsible for Sarfraz’s legal fees as it seems inconceivable that any legal team would have dealt with such a case on a pro bono basis, and the now commonplace ‘no win no fee’ agreement was not then permitted in England. Today, with a requirement for a libel Claimant to prove serious harm to his reputation, rather than simply some harm, the action wouldn’t have got off the ground, but in 1992 it actually made it to trial where, part way through, Sarfraz threw in the towel.

After the aborted trial, in the way that any self-respecting competitor would, Sarfraz claimed victory on the basis that Lamb had acknowledged in evidence that he had never accused Sarfraz of cheating in any match the pair had played together. The court record of course showed a different winner, but that seems not to have worried Sarfraz. A quarter of a century on and the mysteries of reverse swing are better understood, and despite recent events in South Africa few suggest now that Wasim, Waqar or indeed Sarfraz before them were ever “guilty” of anything more heinous than occasionally pushing their luck.

Outside cricket Sarfraz, with the help of his third wife, was to forge a career in politics. He had married first in 1970, to a sister of Test batsmen Saeed and Younis Ahmed, a fact that does not get any sort of mention in Younis’ autobiography so, as a brother in law, he was presumably something of a disappointment. Sarfraz’ second marriage, to a lady doctor from Karachi, took place in December 1976. In turn that marriage ended and then in 1982, whilst she was in London receiving treatment for cancer, Sarfraz met and married Rani Mukhtar, a well-known actress. With her support Sarfraz became an MP in the Punjab Provincial Assembly in 1985, joining the socialist Pakistan Peoples Party in 1988, and later transferring his allegiance to the more centrist Muttahida Quami Movement.

Sarfraz still finds it impossible to live a quiet life. Now 69 he was reported in October 2017 as being involved in two court cases against cricket administrators in Pakistan and of complaining about threats he had received. He cannot be blamed for taking them seriously. Back in the late 1980s he was attacked by a gang outside his Lahore home that left him unconscious and with injuries that necessitated a 15 day stay in hospital. Despite that disincentive to ruffle feathers Sarfraz has been quoted as saying I can’t sit back and let these people ruin the careers of deserving youth. I am fighting a noble cause and I will take them to every available forum.

It seems unlikely that just because the passing years have diminished his ability to bowl bouncers at his opponents that Sarfraz Nawaz intends to go anywhere quietly, and I suspect that one of my favourite Pakistani cricketers has a headline or two to make yet. I wish him well.

Leave a comment