World Sports Magazine Review – April 1950 Cricket

Dave Wilson |

Following the earlier pieces on the sports magazine World Sports, which can be found here , here and here, part four features extracts from a single magazine published in April 1950.

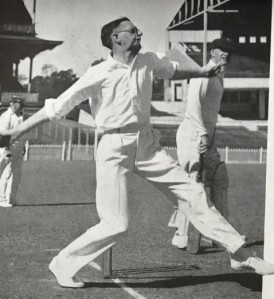

This particular edition was significant as it included a celebration of the 61st birthday of Neville Cardus, written by the great man himself. The piece included a photo of Cardus bowling in 1938, when aged 50 but looking somewhat older. Cardus relates that he was transformed from being an association football fan in 1899 (“soccer” being apparently a term confined to the upper classes at that time) to being a die-hard cricket fan by the following summer, but that he couldn’t remember what specifically had caused such a transformation to take place, although he had initially begun watching cricket to poke fun at the ‘la-di-da’ types who played such a soft game. In the process of this reminiscence, he introduced this reader to a word with which I was not previously familiar, i.e. ‘contumely”, as in ‘as we lay on the grass we shouted contumely at the players’, which means (for those like me who weren’t previously aware) insolent or insulting language – no doubt CW’s own Neville Cardus already knew that.

Cardus grew up watching cricket while firmly entrenched in its Golden Age and the impact of that period clearly shaped his future writing career, as he introduced a romance to cricket writing which was previously absent. He describes in detail a match which took place one Whit Monday between Lancashire and Kent, when the visitor’s opener Cuthbert ‘Pinky’ Burnup, who incidentally was capped for England at football, rescued Kent from 13/3 to 401/6 by scoring exactly 200 not out – in Cardus’ opinion, ‘this day could be quoted as a kind of graph of the temperature of first-class cricket of the Golden Age’.

CB Fry acheived a feat in 1901 which has since been equalled, by Don Bradman and Mike Procter, but never broken, that of six consecutive First-Class hundreds. By 1950, however, Cardus had this to say: ‘We have waxed fat on records now; the currency has depreciated. We have lost the blessings and grace of innocence.’ He goes on: ‘I have no use for those who live in the past’ while reprising one of his more evocative comparisons, which he usually applied to Bradman, of the aeroplane and swallow to illustrate the difference between ‘the mechanical and the vital.’

Cardus had more to say about the state of cricket in 1950 as compared to that enjoyed during the Golden Age: ‘County captains should order any batsman to get out if he is not scoring quickly enough, and goes protectively into a shell because he is approaching yet another “century”.’ Interesting use of quotations there. As a shining example of the type of batsman he favoured, he holds up Ranji: ‘an innings by him was a tribute from the Orient to the glory of the Victorian sunset and the dawn that came up like thunder, too soon to blaze down, with the Edwardian succession’; I honestly can’t imagine any other cricket writer coming up with such a description, or being allowed to get away with writing it for that matter.

As far as his opinion of the best ever, Cardus rates Hobbs as the best all-round batsman he’d ever seen, Trumper the most gallant, the aforementioned Ranji the most magical, Macartney the most impertinent, JT Tyldesley the most brilliant on a sticky wicket and at his best a stroke player in a thousand, Woolley the ‘most lordly in effortless power’, Spooner the most courteous, Leyland the most obstinate, Compton the most likeable, George Gunn the most original, Hammond the most magnificent, Maclaren the most majestic, while it is no doubt Cardus’ romantic view which instructs his estimation of Bradman as the most ‘ruthlessly reliable’.

Of the men at the other end of the pitch, his favourite among the fast men were McDonald, Larwood and Walter Brearley, while he finds praise also for SF Barnes, Tate, O’Reilly, Grimmett, Blythe, Rhodes, Trumble, and Noble…’ after all, as the photo above confirms, he was ‘in my way, a bowler myself!”

As enjoyable as the birthday piece was, the second piece by Cardus in the same publication is decidedly more eye-opening to modern readers. Entitled ‘No Ashes, but Plenty of Fire”, this piece features his preview of the upcoming West Indies tour of England. It is prefaced by a great photo of a youthful looking Frank Worrell, as well as Everton Weekes and Robert Christiani, all of whom had made their debuts when the England team had toured the Caribbean a couple of years earlier.

Cardus performs a service to his readers by introducing them to a number of early West Indian cricketers, including George Challenor, CA Olivierre and Lebrun Constantine, father of Learie. However in so doing, he employs one or two phrases which are somewhat jarring to the modern reader. While it is perhaps harsh to judge those of a bygone age against our relatively recently accepted, but hopefully more enlightened standards of inclusion, nonetheless there are some eye-opening sentiments expressed in this piece, such as ‘large smiles redolent of water melons’ and, in describing the friendliness of Derek Sealy (at least I assume that is who ‘J Sealey’ refers to), making a reference to ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’. I realise I may be displaying a little too much sensitivity, however Cardus also warns against the ‘Old Adam” breaking out which, for those of you unfamiliar with the phrase, is referring to humans in their unredeemed state. Finally, a precursor of Tony Grieg 25 years later, though perhaps not quite as forthright, can be found in Cardus’ summing up of the lack of readiness of the 1928 visit of the West Indies cricket team to England, noting they were too ‘naive in its endeavour and changes of mood…a sudden blow of bad luck! – the outlook darkened at once.’ Different times indeed.

Cardus does however offer Headley as possibly being the greatest batsman of all time, ahead even of Bradman, whilst also crediting him with toughening the fibre of West Indies cricket – ‘Headley lent a contemporary and cosmopolitan sophistication to the sound foundations laid down almost single-handedly by Challenor.’

As many readers will know, it was during the 1950 tour that Sonny Ramadhin and Alfred Valentine (referred to in his article as ‘A Ramadhin and V Valentine’) laid waste to the cream of England’s batting; it is possible that the latter was confusing Vincent Valentine, who played a couple of Tests before the war, but as our resident cricket tragic Martin points out, Ramadhin was never endowed with a Christian name and was dubbed ‘Sonny’, though he was also apparently assigned the initials ‘KT’ by an over-officious customs official prior to an Atlantic crossing. It may have been the sight of Valentine which suggested the comment ‘It is another sign of the greater introspection that is coming to West Indies cricket, as it is drawn into the circle of a world “civilisation”, that their players are taking to spectacles.’

Nonetheless Cardus signs off with ‘Every lover of cricket will rejoice to see the West Indies holding their own with our best’ – well, they certainly managed that.

Leave a comment