The Story of an Essex Fast Bowler

Martin Chandler |

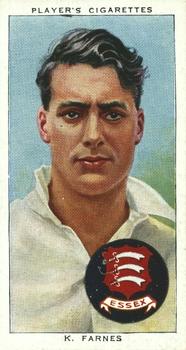

Even now 6’ 5’’ is tall, and in the 1930s it meant the owner of that frame was almost a giant. Ken Farnes was one such. Born in 1911 in Leytonstone in Essex his was a middle class upbringing and he was an exceptionally gifted schoolboy sportsman. He became an international cricketer, bowling fast for Essex and England, but he was a fine all-round athlete, gaining an Athletics blue at Cambridge for the shot putt, as well as for cricket. As a schoolboy he set records in the high jump and long jump.

His school days over this intelligent young man worked briefly in insurance, and then banking, the tedium of both of which eventually led, in May 1930, to his taking in a day at the Australians tour match at Leyton. He didn’t go back and instead decided to go to Cambridge University to study History and Geography. On completing his degree Farnes went into teaching and, until he joined the RAF in 1940, was a master at Worksop College.

As well as making the momentous decision to abandon his banking career Farnes also made his First Class debut in 1930. An opening bowler he was genuinely fast, in the opinion of many the only Englishman, Harold Larwood apart, who merited that description between the wars for any length of time. The tall Essex amateur worshipped Larwood, who he described as a demon of destruction to batsmen, with all the concentrated antagonism that a fast bowler should have.

Speed apart there was little similarity between Farnes and Larwood. Almost a foot in height was the first difference, and they had vastly different backgrounds. Unlike Larwood’s glorious long approach to the wicket Farnes adopted a much shorter run up, just eleven paces, and appeared to amble up to the wicket, his pace being generated by the arm speed and body turn and, to a certain extent, by his mood. The much higher trajectory was inevitable a major difference between the pair, but both men relied on more than mere speed, both being capable of moving the ball both ways.

On debut Farnes failed to take a wicket, but he took 5-36 against Kent in his second match and was a model of consistency after that, always taking wickets at a modest cost and ending up with a career total of 690 at 21.45. He only had three summers that were anything approaching full seasons, those when he was at Cambridge between 1931 and 1933. After graduating he was able to play only during the school holidays, save for the occasional brief release for Tests against Australia or to appear for the Gentlemen against the Players.

The years of 1932 and 1933 are momentous ones in cricket history. In the Australian summer Douglas Jardine’s England unleashed on Australia the fast leg theory bowling that rapidly became known as Bodyline, and the Ashes series in which it was used remains the most talked about and written about in the game’s history. At just 21 when the touring party was selected Farnes did not expect to be chosen, in his own words he was certainly not ripe for it, but he is a small part of the story nonetheless.

In his 1940 autobiography, Tours and Tests, Farnes wrote, of 1932; That was in the bad old days when bumping the ball was in vogue as a technique. The comment suggests, that at that stage at least, Farnes had come to disapprove of Bodyline. The point was made as a preliminary observation before Farnes related a story of an encounter with Yorkshire pace bowler Bill Bowes. The pair cannot have known each other well, and had certainly not played in the same First Class match prior to Bowes appearing for the MCC against Cambridge University at Lord’s in 1932. Nonetheless the two were sufficiently acquainted to have a conversation about field placings for the short pitched delivery whilst walking to the ground from St John’s Wood tube station during the match. Bowes was so enthusiastic about the subject that he even drew a diagram for Farnes to illustrate his point.

The MCC had the better of a draw in their match with Cambridge, with neither Farnes nor Bowes making a spectacular contribution. The students stayed in London as the next game at Lord’s was the 1932 Varsity match against Oxford, in those days one still one of the highlights of the season. The game was a high scoring draw in the end with Farnes, taking 5-98, being the pick of the Cambridge bowlers. The only blemish on his bowling noted by Wisden was a tendency to bowl no balls, perhaps through striving for extra pace and bounce. In any event he must have been bowling very aggressively as he hit a few of the Oxford batsmen. Notable amongst his ‘victims’ was the South African Pieter Van der Bijl. Like Farnes Van der Bijl was a very tall man, but he was a batsman good enough to average more than 50 in the one Test series in which he played. His size meant that Van der Bijl was not quick on his feet, much like the Australian batsmen who came off worst against Harold Larwood and Bill Voce, and despite his innings only extending to seven runs, according to the watching EW ‘Jim’ Swanton Van der Bijl was struck several times by Farnes.

We know that Farnes must have been in the selectors thoughts at this stage because three weeks later he was selected to play in a match between England and The Rest, arranged for the very purpose of assisting the selectors in their deliberations. Farnes found himself opening the bowling with Larwood, put in the Rest’s side because the selectors wanted to see how their frontline batsmen shaped up against him. Unfortunately the match did not help them very much, just 79 overs being possible, all on the first day. England won the toss and batted and there was a fine innings from Duleepsinhji as Jardine’s side got to 180-3. Farnes had figures of 18-5-37-0 and Wisden described him as bowling uncommonly well without, however, meeting with any success. Unbeaten on 40 when the rain came Jardine must have had a good look at Farnes.

Shortly before Jardine’s men sailed another quick bowler was added to the party, and the man who got the nod was Bowes. Late in the season Jardine had spent plenty of time at the wicket for Surrey against Yorkshire, watching Bowes bowl so many bouncers at Jack Hobbs that the normally unflappable ‘Master’ rather lost his cool. It is inevitable that Bowes’ performance in that game would have impacted on the selection decision made, as would Farnes’ at Scarborough a couple of weeks earlier. The famous old ground at North Marine Road is not a forgiving place for any bowler whose direction falters let alone a fast one and it is likely that the rough treatment meted out to Farnes by Herbert Sutcliffe and Maurice Leyland, who at one point took 75 runs off just four of his overs, put paid to the possibility of his going to Australia.

The following English summer was an interesting one. Once the English players saw what Bodyline was attitudes began to harden against it and, given the status the match had, Farnes bowling in the Varsity match attracted much comment. Despite his later ‘bad old days’ comment Farnes was a willing participant in his captain’s plans to bowl Bodyline, and happy to accept that intimidation played a role in what he was doing. His figures in a drawn game were pretty good as well, 3-44 and 4-27, but the press were not impressed. It was not so much the principle that seemed to cause objection as the shortcomings in the way the bowling was actually delivered, The Times observing that Farnes was so inaccurate his short legs might as well have been positioned in the Mound Stand.

The public had another good look at Bodyline a couple of weeks later when Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale hurled it down at England in the second Test at Old Trafford. As at Lord’s in the Varsity match the wicket was not a fast one, so in some ways what was seen was just a shadow of what the Australians had faced. Jardine showed everyone how to deal with that sort of bowling however as he took his only Test century from the West Indies. But the tide had turned against Jardine and by the time the Australians arrived in 1934 Bodyline had, effectively, been outlawed.

1934 was never going to be easy for England. With Larwood and Voce out of the running as a result of their refusals to apologise for their bowling in Australia, Gubby Allen not available and, for the first Test, Bowes injured, the fast bowling stocks were low and Farnes lined up for a debut in the first match of the series despite having taken only five wickets in the three matches he had appeared in. Three of them were Australians, but there had been an unimpressive 1-132 in the Test trial, although there was a second victim there, skipper Bob Wyatt, whose thumb Farnes broke.

With a pace attack comprising Farnes, Leicestershire’s George Geary and the reluctant bowler Walter Hammond England lost the first Test by 238 runs. Farnes, however, had a fine debut and, had he had some support, the result may have been different. His figures were 5-102 and 5-77 and his bowling was praised by all who saw it. When he got back to school after the match he was chaired up the drive by his pupils. Retained for the second Test at Lord’s Farnes was not fully fit, having hurt his heel in the crumbling footmarks in the first Test. He failed to take a wicket, although that itself mattered little as Hedley Verity took 15 to take England to victory, but the injury was aggravated and Farnes missed the rest of the series.

When Farnes did return he took plenty of cheap wickets for Essex in the closing weeks of the summer and was rewarded with an invitation to tour West Indies with England. The College were prepared to let him go, although he would have to forego £100 of his salary. To go some way to making that up the MCC were prepared to award £25 to Farnes who decided the opportunity was one he could not miss.

The West Indians had not troubled England unduly in 1933, but it was a different story in 1934/35 when they won the series 2-1. England had not taken a full strength side, but the real problem was that there were only 14 men chosen and the team was often lopsided. Farnes strained a muscle in his neck early in the tour and the effects of it were with him throughout. He did play in two Tests, the first and last, but the injury meant he was some way below his top speed.

Looking forward to playing against South Africa in 1935 Farnes hoped his luck would change, but in fact he missed the whole season. It was a ridiculous accident that caused the problem. Out walking Farnes had a fence to negotiate, which involved utilizing a tall tree stump. Putting his left foot on that and levering himself up he damaged his knee so badly he needed surgery. Fortunately the operation went well, and although the recovery was a long one, it was also a complete one.

Still only 24 when the 1936 season began Farnes was extremely fast for the Gentlemen against the Players in the Lord’s showpiece, a match that doubled as a trial to assist the selectors to choose a side to tour Australia in 1936/37, a trip Farnes was keen to make. When term ended, having made him unavailable for the Tests against India, he also took plenty of wickets for Essex and, in the game at Taunton, came tantalisingly close to what would have been his only First Class century. He and wicketkeeper Tom Wade put on 149 for the tenth wicket and on Wade’s dismissal Farnes was left high and dry on 97. He had made 56 for Cambridge against Middlesex in 1932, but those were his only two half centuries and a career batting average of 8.32 tells its own story.

In Australia Farnes had a mixed time. He did not do enough to get into the side for the first Test, unexpectedly won by England. When the second Test was won as well the side was fixed until, for the fourth, there were concerns over an injury to Voce. The Notts left armer played but, to provide some cover, so did Farnes. He bowled pretty well, and took a couple of wickets in each innings but couldn’t stop Bradman making the second innings double century that carried Australia to victory.

The final Test was reminiscent of Farnes’ debut. It was a crushing Australian victory by an innings and 200 runs as they completed their comeback from 2-0 down. The Australians totalled 604 in their innings, Bradman scoring 169 before being bowled by Farnes, one of six victims for him. His final haul of 6-96 was to remain his best Test performance.

For 1937 England’s visitors were New Zealand, although teaching commitments meant that Farnes was only ever going to be available for the final Test. Not for the first time by the time the game arrived he was not fully fit anyway, a side strain affecting his pace. He did play for Essex and bowled within himself but, unsurprisingly the selectors did not want to pick him on that basis. It was unfortunate as in the Gentlemen v Players fixture at Lord’s he had shown fine form, taking 5-65 and 1-28.

Only once did Farnes take a hundred wickets in a season, and that was to be in 1938. As it was an Ashes summer Worksop were happy for him to appear in all the Tests, so greater availability was part of the reason, but his season was still restricted to 19 First Class matches, in which he took 107 wickets at 18.84. Duly selected for the first Test Farnes did pretty well. On an excellent pitch at Trent Bridge England piled up 658-8 before declaring and might have won had Stan McCabe, a man who Farnes often dismissed, not recorded 232, an innings of such quality that Bradman summoned the entire team onto the pavilion balcony in order to watch it. The next best score was 51 from Bradman himself, and while McCabe could not save the follow on, he took sufficient time out of the game to ensure the draw was within easy reach. For Farnes there were figures of 4-106 in the first innings.

Moving on to Lord’s another draw followed with Farnes taking three more wickets although, surprisingly, that was not enough to keep him in the 13 for the third Test at Old Trafford. In the event it mattered little however as that match was abandoned without a ball bowled, and events at the Gentlemen v Players match shortly afterwards guaranteed that Farnes would be reinstated for the fourth Test.

The amateurs won the toss, decided to bat and got to 411 before leaving the Players with a quarter of an hour’s batting. In the event there was time for just one incident packed over from Farnes. First of all he produced a very fast delivery that leapt at Bill Edrich. The delivery brushed Edrich’s glove before hitting him on the forehead and flying to Hugh Bartlett at slip. Edrich was knocked senseless and it was several minutes before he was well enough to realise he was out. There was then another long delay before Middlesex wicketkeeper Fred Price emerged from the pavilion. He had not wanted the job of nightwatchman and was out second ball, touching another fast one from Farnes to slip. By the time Eddie Paynter got to the crease there was just time for him to block out the rest of the over. Next day there were six more wickets for Farnes, five of them bowled, to leave him with 8-43, the best return of his career. In the second innings he added three more wickets as the Gentlemen recorded a rare victory.

The fourth and fifth Tests were the two that produced results, Australia winning the fourth and, in that timeless match at the Oval England winning the fifth by the massive margin of an innings and 579 after Len Hutton’s 364. There were five wickets in each of the two matches for Farnes, who ended the series with 17 wickets at 34.17. He was England’s leading wicket taker.

What turned out to be Farnes’ final series was in South Africa in 1938/39, an immensely enjoyable tour for all concerned even if the cricket was a little disappointing, ending as it did with the notorious timeless Test, left drawn after ten days to enable England to catch their boat home. Wisden expressed disappointment in all the England bowlers, no doubt with some justification but the wickets appear to have given little encouragement and Farnes’ bare figures, 16 wickets at 32.43 do not look too bad at all, and were second only to Hedley Verity.

The trip to South Africa had meant that Farnes missed two complete terms and Worksop would not therefore allow any further leave to enable him to play any early season cricket in 1939 other than the Gents v Players fixture where, despite the Players winning comfortably enough, Farnes took 5-78 in the victors’ first innings. He then had seven matches for Essex in August, in which he did enough to end his final season with 38 wickets at 19.10.

After the outbreak of war Farnes spent another academic year at Worksop before leaving teaching in order to serve his country. He played a little cricket in 1940, one of his last matches being for a Lord’s XI against the Public Schools. Some mighty fast bowlers, and still not yet 30 Farnes was still in his prime, might have gone easy on the youngsters, but Farnes afforded them the respect of doing his best. In their first effort his 7-25, hitting the stumps six times, overwhelmed the youngsters but they put up a better display second time round, Farnes second innings figures being 3-62.

Farnes joined the RAF and trained as a pilot, largely in Canada, and returned to the UK in 1941 where he was killed on the evening of 20 October 1941 near Chipping Warden in Northamptonshire. He had been based there for a month, readying himself for the job of flying Wellington bombers. He had wanted to be a fighter pilot but his height prevented that. On the evening of his death he was taking his first unsupervised night flight as a training exercise. A landing went wrong and Farnes was killed instantly. He was single at the time of his death and had never been married, although it seems he had found his life partner, a divorcee whose only daughter went on to marry the film critic Barry Norman and who retained into old age fond memories of the man she believed would have been her step father but for that tragic night.

Leave a comment