The Golden Eagle

Martin Chandler |

There have been some breathtaking pieces of fielding in Test cricket, and for those fortunate enough to have seen them they are almost as memorable as the great innings and spells of bowling that litter the annals of the game. But the individuals concerned are always remembered primarily for their batting, or their bowling, or sometimes both. There are only two cricketers who, it seems to me, are regarded first and foremost as fielders, and both are from Southern Africa.

It is easy to remember Jonty Rhodes, a man whose 52 Test career finished as the new millenium dawned. He was a good enough late middle order batsman to average just over 35, and to score three centuries and 17 fifties, but it is his fielding that springs to mind first whenever his name is mentioned. The other man who makes up the duo is The Golden Eagle, Colin Bland and, given that many in the 21st century are not immediately sure whether he was a batsman, bowler or all-rounder, he is surely the more vivid example. This is all the more surprising given that Bland the batsman averaged just a tick under 50 in his 21 Tests. He was no minnow-basher either. The weakest side he played against was New Zealand, but his record against the Kiwis was markedly inferior to that against Australia and England.

Perhaps inevitably in the circumstances Bland was a fine all-round sportsman. At school he was an excellent Rugby Union player, and in his own opinion that may have been the game where his greatest abilities lay, but he professed no great passion for the oval ball game, and eventually gave that up as his winter option in favour of hockey. So good a hockey player was he that, had he not chosen to stay at home to prepare for the England tour of 1964/65, he would have gone to Tokyo to represent his country in the 1964 Olympics.

Cricket was Bland’s great love however. He was born in Bulawayo, then in Rhodesia, in 1938 and 18 years later made his way straight from the examination room to Salisbury to make his First Class debut for his country against Peter May’s England. It was to be an eminently forgettable match for the nation, they lost by the overwhelming margin of an innings and 292, but to the extent that it can be so in those circumstances the game was a personal triumph for Bland. There was certainly no doubt about his fielding ability. was the comment of South African broadcaster Charles Fortune in relation to his performance in England’s 501 all out. In the debacle that was his side’s reply, 57 all out, the young Bland, who walked to the middle at 7-5 with Frank Tyson and Peter Loader operating, top scored with 19. In the second innings, a little better this time at 152, he did so again, a fine innings of 38 only ending when Tony Lock, from his own bowling, took the sort of catch that Bland himself was to become famous for.

After such a promising debut Bland’s subsequent progress was not particularly spectacular, although a better 1960/61 season won him a place with the South African Fezelas who toured England in 1961. This was a side captained by Test player Roy MacLean and was made up of a number of promising young players including, in addition to Bland, Peter Pollock, Denis Lindsay and Eddie Barlow. The Fezelas overwhelmed most of their opposition, including Essex and Gloucestershire in First Class matches, but Bland, despite continuing to thrill in the field, would not have been particularly happy with his batting. He must have been a long way from the selectors thoughts as the 1961/62 season opened, carrying with it the promise of a full five Test series against New Zealand. It was Bland’s good fortune that the tour began with two games against Rhodesia, and the locals provided much stronger opposition for the Kiwis than they had for England in 1956/57 as they were just one wicket away from victory when the first match was left drawn, and were in a good position as the rain affected second match petered out. For Bland there were scores of 91, 45, 67 and 58, and as a result a place in each of the five Tests.

Bland’s debut was the last ever Test to be played at the old Kingsmead in Durban. He failed in the first innings but, in a low-scoring match that South Africa eventually won by 30 runs, his second innings contribution of 30 was crucial. Australian writer RS (“Dick”) Whitington wrote that the innings …bore all the hallmarks and portents of a century. before John Waite caused him to be run out in rather bizarre fashion, calling him for a single for a shot he intended to play into the covers, but which ended up going towards mid-on. As Bland failed twice in the drawn second Test that may have been that but the selectors stuck with him for the third Test. New Zealand won the match by 72 runs to record only their second ever Test victory. Bland only contributed 32 to his side’s first innings of 190 but Whitington commented that he barred the way to greater disaster with a display of batsmanship that nobody in this match, Reid* apart, had equalled…..the same bloom was on his batting as had adorned his fielding the day before. South Africa’s victory target was 408, which to their credit they had a go at. Of Bland Whitington’s words this time were that he demonstrated the measure of his unfolding class and maturity in scoring 42 at the crisis time.

When South Africa took the lead in the fourth Test with an innings victory Bland contributed just 28, but in Whitington’s view was still responsible for the incident that turned the match in his team’s favour. New Zealand batted first and were 130-4 with Reid in imperious form on 60. Quick bowler Goofy Lawrence was operating and Reid launched all of his considerable strength at a cover drive and sent the ball skimming towards the gap between Bland at cover and McGlew at mid-off, no more than 18 inches from the ground. Bland dived full length to make the catch. I will quote Whitington here at some length, as his words explain as eloquently as any I have seen just how good a fielder Colin Bland was I have watched Jack Hobbs run out the youthful Don Bradman from cover, after “foxing” for some time with his throw to suggest that his arm was no longer what it had once been. I have seen Victor Richardson, dashing at right angles to the flight of a low and fierce dancing drive from Tommy Andrews, hold the ball at full speed with his two hands beside his ankle. I saw that miracle of a gully catch by Richie Benaud, which made Colin Cowdrey rub his eyes in wonder. I have watched Neil Harvey field in most of his seventy Tests, and Russell Endean take a “Statue of Liberty” catch at long-on at the MCG in 1952. I saw “Mr Electric Heels” Learie Constantine, bounding about like a black shadow against the hard light at Adelaide in 1931. But I very seriously doubt whether any of the miracles of agility they performed measure up to the catch Bland held at the Wanderers on February 2 1962.

In the fifth Test New Zealand famously squared the series and, with 12 and 32, Bland again got two starts that he failed to capitalise on and a series average of just 22 meant that he was by no means established. He had a mediocre season in 1962/63, and indeed without his one big century against North Eastern Transvaal would have averaged less than 20. However the selectors stuck with him in choosing the touring party for Australia and New Zealand the following year, although his form on arrival was such that he was not selected for the first Test, drawn amidst the sad end to Ian Meckiff’s career. Bland still played a role in the game though, unsurprisingly made twelfth man he ran out Peter Burge, sent back by Norm O’Neill once he realised who the fielder was, and throwing himself forward to catch Bob Simpson at mid-wicket in Australia’s second innings.

In the second Test Bland and Peter Carlstein, the man he replaced in the team who fielded almost throughout as a substitute, had the ground ringing with applause for their dynamic interceptions and superlative throwing, but Bland would have been more pleased with the innings of exactly 50 he made in his side’s first innings. He would have been less happy with what happened when Australia were 30-0 in a first innings that went on to total 447. Ian Redpath was 30 at the time (he was eventually to be the first wicket to fall, 189 runs later). Bland was fielding at the unaccustomed position of short leg, and the sort of chance that Geoffrey Boycott’s grandmother could have caught ballooned up from bat and pad. Bland missed it, remarkably not even getting a hand to the ball with his despairing lunge. To complete his embarassment he fell on his face, grazing his knees and elbows, and tearing his shirt. He explained later that he was not used to fielding so close to the bat and that he had been unable to focus properly. Four more catches went down afterwards, so the blame for the long opening partnership could not really be laid at Bland’s door, but his was the one of those drops that was always talked about.

After Australia won the second Test many spectators were disappointed that South Africa did not make an effort to chase a 409 victory target in the third Test, but at least they had the consolation of watching Bland score 85 on the last day, as his side closed on 326-5, to go with exactly 50 that he had scored in the first innings, during the early part of which he saw Graeme Pollock through to his first Test century. At Adelaide in the fourth Test the visitors did square the series, a huge partnership of 341 between Pollock and Barlow paving the way for a ten wicket victory. Bland contributed 33 and then, in the drawn final Test, he finally stole the limelight from Pollock with his first Test century, 126 out of 411. In the course of the innings he played what Whitington described as the most memorable stroke of the series, a straight six that landed on the top of the Noble stand at the SCG.

From Australia the tourists went on to a more leisurely three match series in New Zealand. All the matches were drawn with South Africa well on top, and Bland averaged 69, albeit with just one half century coming his way, so it was largely by virtue of his consistency.

Bland was now an established Test player and, in 1964/65, was due to meet England for the first time. It seems difficult to believe that even the best part of a half a century ago news did not travel sufficiently speedily and/or widely for the tourists to be aware of Bland’s reputation, but if they were they certainly allowed themselves to be the victim of the sort of confidence trick that Whitington recalled being played on Bradman by Hobbs back in 1930. As usual the tour began in Rhodesia and the chosen victim was the baby of the England party, Mike Brearley. Bland fielded at cover and Vernon Dickinson, an orthodox left arm spinner, was at mid-off. Several times Brearley pushed the ball towards mid-off and, Bland running towards the ball but not getting down to it in time, left the job for Dickinson and allowed Brearley a comfortable single. The local pressmen knew what was going to happen as soon as Dickinson wandered 10 yards deeper. As an even easier single beckoned for Brearley he set off for the run only to find himself just half way down the wicket as, in trademark fashion, Bland loped in, swooped and threw down the stumps in a single movement.

The game’s history records that, somewhat against expectations, England won the series 1-0 after her spinners, Fred Titmus and David Allen, took full advantage of a helpful pitch in the first Test. This was Bland’s best series with the bat and he was a model of consistency, averaging 71.50 with scores of 26, 68, 29, 144*, 78, 64, 55, 38*, 48 and 22. The unbeaten century in the second Test was desperately needed by South Africa who had conceded a first innings deficit of 214 and were tottering on 109-4 in the second innings when he came in and batted right through the final day to see them to safety and beyond. Charles Fortune described the innings as an epic and wrote On the field Bland moves with a grace that suggests he may be the reincarnation of a Greek god and on this day the gods would readily have taken him as one of their heroes.. Bland first turned back the waves of a rampant English attack, subdued that attack and ultimately bent it utterly to his will. It is an innings like this one that raises cricket to a peak of dramatic intensity such as no other game can achieve. On Bland for hour after long hour lay the full responsibility of keeping his side in the match.

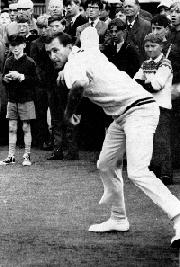

Bland’s selection as a member of the party for the return series in England in 1965 was a formality. The South Africans had the second half of a summer which saw, for the first time since the ill-starred Triangular Tournament in 1912, two visiting Test nations in the same summer. It was also to be the last South African visit for the greater part of thirty years. The low key Fezelas tour of 1961 had not resulted in Colin Bland impressing himself in the consciousness of English cricket followers. This one did though, as he excelled both with the bat and in the field. The first Test at Lord’s was drawn, England hanging on with seven wickets down and 46 left to make. Bland’s 39 and 70 made sure that South Africa had the runs they needed but it is his two run outs in the England first innings that have passed into legend. First was Kenny Barrington, nine short of a century, who ruefully admitted later that he should have known better than to take on Colin Bland. As so often with Bland it was the running pick-up and throwing down of the stumps from mid-wicket that defeated the Colonel. A little later it was Jim Parks turn. A canny customer Parks ran on the line between Bland and the stumps. If he thought that may make him safe he was to be disappointed as the trademark flat throw flew between his legs and ran him out by a couple of yards.

The second Test was the decisive match in the series and, ironically enough, one to which Bland contributed very little in terms of runs (1 and 10), no catches and no run outs, although his ground fielding was still such as to cause Wisden to describe him as taking the fielding honours.

The final Test at the Oval might have been one of the great finishes in Test history, as England ended up 91 adrift of a victory target of 399 with six wickets in hand when a downpour robbed both sides of the last 70 minutes of the game. Colin Bland’s penultimate Test had provided him with the stage for his third and final Test century, 127 in the South African second innings. He was unusually circumspect to begin with, but once the sixth wicket fell and the tail joined him the big trademark drives were unleashed as the South African lead became a formidable one.

There were to be only two more Test series for South Africa before the years of sporting isolation began. Age should not have been a barrier to Colin Bland playing in both, he was still only 27 when he returned from England in 1965, but it was not to be, and there was just the first Test of the home series against Australia in 1966/67 to come. The match itself is one of the more remarkable in Test match history. South Africa slumped to 41-5 (a duck for an out of form Bland) before recovering slightly to 199 all out. Australia took a first innings lead of 126 but still managed to lose by 233 runs as the home side piled up an imposing 620 in their second innings. Bland scratched around nervously for a long time before finally throwing off the shackles with a couple of fours and a six to get to 32 at which point he was fell victim to a perfect leg break bowled by, of all people, Ian Chappell.

In Australia’s first innings Bland’s ground fielding moved former South African skipper Jackie McGlew to write that he …entertained the crowd to a brilliant display of hard running, uncanny pick-ups and bullet like returns which smacked loudly into Lindsay’s gloves, inches above the stumps. Sadly it was the last chance any ground had to see Bland in his pomp as in the Australian second innings, after chasing a ball hard to the boundary, he tripped over a boundary board and damaged his left knee. He needed surgery on his cartilage shortly after the accident and while he continued to play First Class cricket until the end of the 1973/74 season, he retired from the international game. He continued to bat with distinction after the injury, and in 1967/68 played an innings of 197 in three hours for Rhodesia against Border on a difficult wicket that many considered his best ever knock, but he could no longer circle around the covers and swoop on the ball like a hungry bird of prey, and the game lost something as a result. The Golden Eagle took to fielding at slip and his catching ability transferred easily to that position.

Outside the First Class game Bland became cricket and hockey coach at Free State University and Grey College in Bloemfontein in 1971, and his last First Class appearances were as Free State’s captain in the Currie Cup B Section. He was made a life member of the MCC, which doubtless made up to some extent for the disappointment and ignominy of, due to his Rhodesian passport and not therefore to do with apartheid in South Africa, he was refused entry to the UK in 1968 to play for a World XI led by Gary Sobers in a festival match at the end of the English season. He was a great favourite in England after 1965, and there was widespread disappointment that he did not join the star studded side that had been assembled.

It is all but half a century since Colin Bland was at his best and there is no doubt that, since then, fielding standards generally have improved enormously. But how does Bland rate alongside the very best of the last fifty years? The question is impossible to answer definitively of course, as fielding standards cannot be measured empirically with any degree of certainty, and comparisons are therefore futile. That said there are a few men who can make observations which merit serious consideration. One such was John Arlott, who looked at the respective talents of Bland and another magnificent cover point from much the same era, former West Indies skipper Clive Lloyd. Another is Mike Procter, who played with Rhodes and against Bland. Both felt that Bland was very slightly inferior, on the basis that he did not have quite the same degree of athleticism as Lloyd or Rhodes, but when it came to the brilliance of the pick-up and throw, and the regularity with which he hit the stumps, Bland seems to have had the edge.

There is however one thing that can be said with confidence about Colin Bland, and that is that he was an absolute revelation in the early 1960s. It must be the case that the rest of the game has caught up with Bland over the last fifty years, but the measure of the man’s contribution to the game must lie in his statistics – that Test batting average of 49.08, something only 47 men have bettered in the 135 years Test cricket has been played, and which places him above such luminaries as Peter May, Neil Harvey, Ted Dexter and Rohan Kanhai – yet people remember him just for his fielding.

*Skipper John Reid had scored 92 in New Zealand’s first innings of 385.

This is the article I’ve been waiting for. Colin Bland. WAG.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am GMT 25 November 2012

where can I buy the hardback

Comment by uvelocity | 12:00am GMT 25 November 2012

Thanks for the article, always wanted to know more about Colin Bland

Comment by AndyZaltzHair | 12:00am GMT 25 November 2012

Colin Bland may not have played in the 1968 England v West of the World match, but I saw him make 62 (the top score in the innings) in the 1965 match in Scarborough, when the rest of the World team was also captained by Sobers.

Comment by Kevin Riley | 2:15pm BST 10 July 2015