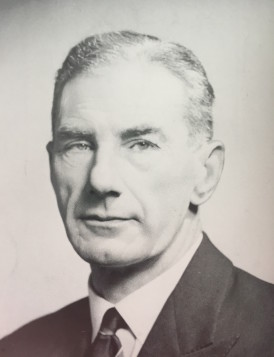

Jim Kilburn

Martin Chandler |

Neville Cardus died in 1973 and, the best part of half a century on, his name is instantly recognisable. Such is his appeal that his life has inspired a couple of books in recent years, firstly Christopher O’Brien’s Cardus Uncovered, now in its second edition, and then last year Duncan Hamilton’s The Great Romantic, a new biography of an iconic figure.

A writer whose cause Cardus championed, Yorkshireman Jim Kilburn was viewed, certainly when I was a youngster back in the 1970s and 1980s, with almost the same level of reverence. Like Cardus Kilburn has also had the Hamilton treatment, albeit the 2007 published Sweet Summers was primarily an anthology rather than a biography per se. Nonetheless whilst that one received the acclaim it was due it did not succeed in bringing Kilburn a new audience in the way that I suspect The Great Romantic has done for Cardus.

There are certainly differences between Kilburn and Cardus. Whilst Cardus was very much a Lancastrian he, spending his later life in Australia and London, took more of a world view than Kilburn who, for his entire journalistic career, which ended in 1976, was never tempted beyond his position at the Yorkshire Post. His style of writing was very different as well, lacking the lyrical style of his Mancunian counterpart’s more florid prose. It is probably also worth making the point that, unlike Cardus who certainly does have and always has had his detractors, it is impossible to find any negative comments about Kilburn.

Born in Sheffield in 1909 Kilburn’s father played cricket in the hard school of the Bradford League. Kilburn himself was to appear in the same arena but his early playing career was for Barnsley in the Yorkshire Council. A very tall man, well over six feet in height, he bowled quickish offbreaks. At Sheffield University in 1930 he assisted their eleven to its first ever UAU Championship and took a nine wicket haul against Liverpool so he was clearly a more than useful cricketer. One suspects that had he come from the south of England invitations to appear for his county as an amateur would have been received.

As it was after a grammar school education in Barnsley Kilburn secured a degree in economics and then spent three years as a schoolmaster in Harrogate. Always a keen writer he wrote plays for the school’s dramatic society and had some sketches and articles published in local newspapers. As a consequence the level of interest shown by the Yorkshire Post was such that when, at the end of his period of teaching he travelled to Finland he was invited to submit articles on his travels for publication.

When the 25 year old Kilburn returned to Yorkshire in the summer of 1934 he found the editor of the Yorkshire Post sufficiently impressed with his work to offer a three month trial as the paper’s cricket correspondent. Kilburn had some big shoes to fill. His predecessor, Alfred Pullin (‘Old Ebor’), had been a respected figure for many years. Pullin had retired in 1931 but had continued to write for the paper as a freelance until he collapsed and died of a heart attack on his way to the Lord’s Test in 1934.

One of Kilburn’s earliest assignments was the ‘Roses’ match in that season of 1934 against Lancashire at Bramall Lane in Sheffield. Sharing a press box with Cardus the man who by then had already acquired his lofty reputation was so impressed with his young colleague that he felt compelled to write to his editor in effusive terms. A permanent appointment swiftly followed together with a doubling of the Kilburn salary. He even, unusually for the time and certainly for the Yorkshire Post, was allowed to write under his own name rather than having to use a soubriquet.

Unusually amongst cricket correspondents Kilburn was universally popular with the players that he wrote about. No doubt his pleasant and straightforward but businesslike manner assisted him in that, as did his thorough understanding of the technical aspects of the game. Above all however was his refusal to write about anything other than the cricket that he saw on field. Anyone could take Kilburn into their confidence knowing that nothing would be disclosed.

There is a well known story that illustrates Kilburn’s attitude which relates to a match at Headingley when a message was received at the Yorkshire Post to say that his copy would be delayed. Somewhat perplexed by this departure from his usual reliability the office then contacted Kilburn to find out the reason and were told that the grandstand was on fire. Understandably Kilburn was asked whether he had contacted the news desk with this story, and his reaction was a blunt I am here to report cricket, not fires.

So what of Kilburn’s writing? He was at his best and most perceptive when writing about the players themselves and, of course, coming from Yorkshire, he had a rich variety of characters with which to deal. There was the immaculately turned out and consummate professional Herbert Sutcliffe, of whom Kilburn wrote; To watch one of Sutcliffe’s innings is to have complete understanding of his power. He always seemed to me rather to hurry to the wicket, everlastingly anxious to be batting and eager to test the quality of a bat which looks brand new every time he opens an innings. Nine times out of ten the first ball will be outside the off stump, and just so often will Sutcliffe step across, bring his feet together with military precision, lift that beautiful bat high out of harm’s way and gaze past point as the ball thuds into the wicketkeeper’s gloves. The padding up announces as clearly as spoken words “my dear bowler, you are wasting your time. I am proposing to make a century today”

He also had one of the finest fast bowlers of them all appear in Yorkshire just after the war, and of the chaos that ‘Fiery Fred’ caused amongst the Indian batting in 1952 he wrote; Trueman did not bat in the (England) second innings. Other business was in hand for him, beginning at 12:30 in nine overs he tore the frail Indian innings to shreds as a tiger would devastate a cage of canvas. He bowled as fast as any man has bowled at Old Trafford these 20 years and more, hurling himself into splendid and thrilling action with the allies of a following wind, a lively pitch, and indifferent light.

And Kilburn could write superbly of the lesser players as well and his description of all-rounder Emmott Robinson is as compelling as anything written by Cardus, who of course invented Robinson. Kilburn described him as; the most completely Yorkshire character – virtues, failings, appearance and all – ever to play for the county, and had he never taken a wicket or made a run or held a catch, he would have been an important factor in psychological warfare. As to Robinson’s bowling Kilburn conjures that up with; he was a new ball bowler of considerable potency, and through the 1920s his shambling run up, prefaced by a little kick off as though he was starting a motorcycle, marked daily onslaught upon the enemy’s opening batsmen.

But a man didn’t have to hail from the Broadacres for Kilburn’s pen to have his measure, as his summary of the ‘Notts Express’, Harold Larwood, makes clear; It is in the matter of accuracy that Larwood is without peer amongst fast bowlers. Actual speed of one man as against another must always remain a matter of argument, but of Larwood’s astonishing control of length and direction there can never be two opinions. Herein is Larwood’s greatest attribute, for without accompanying control mere pace has little terror for batsman with any pretensions of class on wickets that are mostly made for their liking. It is because Larwood is a master of his pace and does not use it blindly in sheer exuberance of spirit that he has known such high and such prolonged success. He rarely gives a batsman peace, for even at the times of his most ferocious attack, or when the inward fire is waning, a loose ball is an unexpected event.

Quite rightly Kilburn’s reputation is founded on the material he produced year in and year out for the Yorkshire Post, but there were a few books along the way as well. In truth Hamilton’s anthology, thoughtfully compiled and bookended by an excellent biographical essay and a collection of testimonials from the great and the good is probably the best place for anyone interested in reading the best of Kilburn to start but for a book a thing of beauty, very nicely designed as Sweet Summers is it cannot compete with Kilburn’s first book, In Search of Cricket, published in 1937 and worth buying for its dust jacket alone.

In Search of Cricket was itself nothing more than a collection essays, in the main culled from Kilburn’s columns in the Yorkshire Post, a number of which do appear in Sweet Summers. It was followed a year later by In Search of Rugby Union, a similar collection (albeit with nothing like so attractive a jacket) and, as far as I know, the only book on the oval ball game that Kilburn wrote.

There were no books from Kilburn during the Second World War but a number afterwards. He was also one of the many journalists who accompanied the England team to Australia for the first post war Ashes series in 1946/47 and, his great friend and fellow Yorkshireman Hutton leading them he went again in 1954/55. Kilburn did not contribute to the glut of books that appeared on wither tour, but did write Cricket Decade in 1956, a book examining international cricket in the ten years since peace had returned.

Kilburn also wrote a small book on the subject of the Scarborough Festival. There were two modest histories of the Yorkshire club, and one much more substantial volume, published in 1949, which followed on from previous books by RS Holmes and Pullin. There was never a biography of anyone else, although he did write a substantial booklet in 1951 on the subject of Hutton, which ran to a second edition. There was also a book, written with former England and Yorkshire captain Norman Yardley, on the subject of cricket grounds.

One can only assume that Kilburn never had the desire to write up anyone’s life, and he would surely have had the members of the great Yorkshire teams that he saw keen to engage him as a ghost had he been that way inclined. That he had the necessary skills to write that sort of book was made clear in 1972 when his autobiography appeared. Thanks to Cricket was an engaging and easy to read memoir that was the Cricket Society Book of the Year in 1972. Three years later Overthows, another dip into the Kilburn memory banks, was an equally satisfying book. Sadly however that was to be it. In 1976 Kilburn retired from the Yorkshire Post, which might have given him the opportunity to give us more but unfortunately his eyesight rapidly deteriorated, so that was that. At least he was, despite his handicap, still able to go matches and, in the words of his obituary in Wisden in its 1994 edition, he remained an upright, dignified man until he died.

For a final few words about Kilburn with which to close I thought I would cast my eyes around for someone still with us who shared a press box with him which, realistically , is either David Frith or John Woodcock, or both. In the case of both Hamilton did the hard work for me. Woodcock began the tribute he contributed to Sweet Summers with Jim Kilburn wrote as he lived – with disciplined, somewhat austere urbanity. He was no more likely to construct an untidy sentence than to raise his voice. Indeed of all one’s colleagues in the cricket press box over many years he was the most imperturbable, and no one’s writing was more clearly a reflection of his character.

And I will go to the other end of Frith’s tribute, as he concluded with; As I look around me now in the so called ‘media centres’, with the predominantly history-allergic writers and their mass of electronic gadgetry, I do sometimes picture the reassuring figure of JMK with his solemn, shrewd gaze, his imposing nose and, of course, that thick nibbed pen which he used to put to such charming use.

Leave a comment