Godders

Martin Chandler |

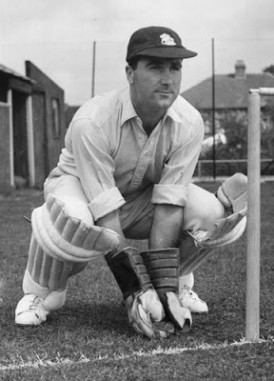

In the 1930s the best wicketkeepers generally eschewed the spectacular. Some of them could be noisy, the stentorian tones of George Duckworth something I remember being told about many times as a child, but the glovework tended to be neat and unobtrusive. Godfrey Evans was something very different. He threw himself around in a way seldom seen before, and made sure everyone knew he was around.

Born in Finchley in 1920 Evans was qualified to play for Middlesex as well as for Kent, but his family left London for Margate when he was six months old. Sadly his mother died when he was just three years old and, with his father being an engineer who travelled for work, he was brought up largely by his considerably older sister and grandparents. It might have been a difficult upbringing, but there was a large extended family and a decent standard of living so Evans had a happy childhood.

When he took up the game Evans showed great promise as a batsman and perhaps the confidence gained from the runs he scored was, in part at least, the reason for the flamboyance he showed behind the stumps. Les Ames was Evans’ hero from the very start, but those who coached him tended to want him to concentrate on his batting. Evans wanted to keep wicket however, and probably realised early on that however good a batsman he might be he wasn’t ever going to be Ames’ equal.

After a trial with Kent in the summer of 1936 the 16 year old Evans was offered a contract for the following season and he began playing for the club and ground side. The following summer he stepped up to the second eleven. At the same time he signed terms to box professionally as a light welterweight (up to 10 stone). He enjoyed some success in the ring but was told, on turning up at Canterbury one day with a broken nose, that he had to make a choice between the two sports. Not without some hesitation Evans chose cricket. He always maintained that his boxing greatly improved his footwork.

It was in 1939 that Evans made his Championship debut. He played purely as a batsman and was dismissed for 8 in his only innings. He was caught on the fine leg boundary hooking Alf Gover, the fastest bowler he had seen to that date. A week later he played again, and this time did keep wicket. He held just one catch, diving full length to the leg side to catch an inside edge one handed. Ames was at short leg and wrote later that he realised at that moment that Evans had arrived.

Like so many others Evans then lost six seasons to the war, but he had done enough to get noticed and when available was regularly selected for the exhibition matches that took place at Lord’s during the hostilities. After war was declared Evans initially worked for a bakery that was the family business of one of his fellow young professionals at Kent, but in 1940 he enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps, lying about his age in order to do so.

By the end of the first post war summer of 1946 Evans was playing for England, picked for the final Test against India and with a place booked in the party to tour Australia in 1946/47. He was 26 by now, but still the youngest member of an aging England side. He had a bad start in Australia however, dropping Don Bradman twice in a state game.

Left out of the side for the first Test Evans was picked for the second as the first choice, Yorkshireman Paul Gibb, struggled to keep to Evans’ county colleague, Doug Wright, a leg spinner who bowled at a brisk medium pace. Evans kept for 11 hours 40 minutes while Australia piled up 659/8 without conceding a single bye, and indeed in the third Test through another 365. Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly described him as being the equal of Australia’s Don Tallon. Wisden described both men as keeping magnificently. It was during this match that Evans made a technical adjustment to his keeping that was to stay for the rest of his career. The great Australian pre war ‘keeper Bert Oldfield suggested he link his little fingers together.

It is true to say that Evans missed more chances than some of the great keepers, but he also held many that others would not even have seen as chances, and his skill at pulling off leg side stumpings from the bowling of men like Alec Bedser was second to none. In The Cricketer’s Spring Annual for 1947 a fine Australian writer, Ray Robinson, wrote that his quickness and certainty on the blind side could not be excelled.

Another factor that cannot be underestimated with Evans was his qualities as a team player. He had spent much of his war as a Sergeant, and was therefore used to responsibility and he was always trying to cajole and encourage. As opponent Keith Miller wrote later; there has been nobody like him for lifting tired fieldsmen late on a hot day. His value to England was incalculable.

In time Evans would record a couple of Test match centuries, and he scored almost 15,000 First Class runs at 21.22, generally at a brisk rate. In 1946/47 he scored only 90 runs in his eight innings with a high score of just 29, but in the fourth Test he did get into the record books. England were 2-0 down already and with 45 minutes of the penultimate day left Evans went out to join Denis Compton. England were 228 in front with eight wickets down. Skipper Wally Hammond implored Evans to get his head down. Evans took the entreaty quite literally, and was still there at the close, yet to get off the mark.

Next morning Evans and Compton went on and on, Compton to his second century of the match, and Evans to a new record of 95 minutes without scoring. When the declaration came he had spent two and a half hours over 10.

Now established as England’s first choice Evans was ever present at home against South Africa in 1947, in the Caribbean the following winter and against Bradman’s ‘Invincibles’ in 1948. He maintained a consistently high standard behind the stumps although his batting remained fragile. The only real disappointment would have been his performance on the final day of the Headingley Test in 1948 when the Invincibles chased down 404 for victory at a canter. Arthur Morris and Bradman put on 301 for the second wicket. Evans was not the only man to let himself down in the field, but a missed catch from Bradman and stumping from Morris were not too difficult.

From the second Test in 1946/47 Evans played 22 consecutive matches for England before losing his place in the side in South Africa in 1948/49. There was no loss of form however, a disciplinary transgression being the cause of his omission. There were two incidents. The first came in a match against Rhodesia when, the Englishmen feeling they were on the wrong end of some seriously biased umpiring, Evans produced an unnecessarily loud and protracted appeal to the embarrassment of his captain. Later, in taking offence at some criticism that was levelled at him, he poured a drink over the head of the tour manager, Brigadier Green. He missed both of the last two Tests.

By the time the 1949 New Zealanders arrived Evans had served his penance and played in all four Tests and he kept his place against West Indies in 1950. After breaking his thumb he missed the last Test of the tourists’ unexpected 3-1 win, but he at last showed what he could do with the bat.

The Test England won was the first, and they won it comfortably enough in the end but without Evans England’s first ‘blackwash’ may have come more than thirty years before it eventually did. On a strange Old Trafford wicket Evans joined Trevor Bailey at 88-5 with Hutton retired hurt. The pair put on 161 together, 104 of them from Evans in ten minutes less than his 10 took him in 46/47. He hit seventeen boundaries and changed the course of the game. Another good innings, 63, came in the third Test, although that was a case of too little too late.

The thumb was nicely healed by the time Evans set off for Australia for the 1950/51 Ashes. Amidst a 4-1 defeat Evans enhanced his reputation considerably but the following summer was a disappointment. Evans felt jaded, played in the first Test whilst injured and did not perform with his usual panache behind the stumps or with the bat. He gave way to Yorkshire’s Don Brennan for the last two Tests against the South Africans and chose to stay at home and not make himself available for the 1951/52 tour of the sub-continent.

Back to his best in 1952 Evans had his best ever season with the bat, scoring more than 1,600 runs. He recorded two centuries, one of them in the second Test against India. He almost got a century in the morning session, getting to 98 before going on to 104. There were two more fifties in the Tests, and another five for Kent.

At the peak of his career Evans performed splendidly against the Australians in 1953, when the Ashes were finally wrested back for the first time since ‘Bodyline’, some twenty years previously, and although an assortment of injuries conspired to mean Evans had to miss one of the Tests in the Caribbean in early 1954 he kept well there too.

In 1954 England failed to give Pakistan enough respect on their first tour and the visitors recorded a fine win at the Oval to square the series, but after that Frank Tyson, who Evans was for once happy to stand back to, helped England to beat Australia 3-1 in 1954/55. After that with one exception England won every series they contested for the next four years. Only in South Africa in 1956/57 did they fail, allowing the home side to come back from 2-0 down to square the series. Evans missed just two Tests in that time, both against South Africa in 1955. The circumstances are a vivid illustration of Evans’ courage.

England won the first two Tests of the series so led 2-0 going to Old Trafford. Peter May won the toss and batted. England were all out for 284 thanks almost entirely to 158 from Compton, his final Test century. On the third day, with South Africa looking for a substantial lead, Evans suffered a knock on his little finger. He knew he had done some damage but played on despite, when he checked the damage at the fall of the next wicket, finding his finger bent, swollen and jet black. Despite May’s suggestion that he leave the field Evans stayed on. Later it was discovered he had broken the finger in two places and, thanks to playing on, the marrow had been squeezed through the joints.

The hand went straight into plaster over the rest day. On the Monday South Africa batted on and were all out with a lead of 237. At the close England were 13 in front with four wickets down. Next day the ninth wicket fell with the England lead just 96, nowhere near enough. With an improvised glove protecting the cast not only did Evans agree to bat but he scored 36 in a last wicket partnership of 48 with Bailey. He almost saved the game. South Africa got home with three minutes to spare and seven wickets down. Unsurprisingly, by then the injury was so severe as to cause Evans to miss the rest of the season.

Fit and firing again for the 1956 Ashes Evans played a full part in the retention of the Ashes in a series which will always be remembered for Jim Laker’s 19-90 at Old Trafford. That winter Evans had turned 36 but was at his very best in South Africa where he played in all five Tests and attracted lavish praise from EW ‘Jim’ Swanton. To the extent that a ‘keeper’s performance can be measured by the catches and stumpings he makes this was Evans best series. He held 18 catches and made two stumpings. The 15 victims he had amongst the 1957 West Indians was his third best haul for a full series.

After a gentle workout against a weak New Zealand side in 1958 Evans embarked on his final tour, to Australia and New Zealand. On paper it was an immensely strong England side, but the years were passing and morale was not what it had been in the past. Evans wasn’t directly involved in any of the real problems but he thrived on a strong team spirit , something that was sadly lacking in a series that England lost 4-0 amidst much anger at the manner in which certain of the Australian pace attack bowled.

From a purely personal point of view the series was unsatisfactory for Evans as well. In the second Test he had to dive whilst batting in order to regain his ground and chipped the little finger of his left hand. As already demonstrated Evans wasn’t a man to take any notice of a bit of pain so he played on, but he still missed the third Test. Back in the side for the fourth match there was another broken finger, this one sustained whilst behind the stumps and diving to try to take a Tyson delivery. This one was rather more serious, and Evans’ tour was over. In summing up the trip Wisden described him as another stalwart who gave evidence of a decline in power.

How long could Evans hang on? He began the 1959 series against India with 89 caps and he must have harboured thoughts of getting to the, in those days unapproached, figure of one hundred. In the second Test however he had what Wisden described as a bad quarter of an hour, and that was that. When the side for the third Test was announced there was no Evans, Roy Swetman of Surrey replacing him in a move the selectors described as being in the interests of team building.

Returning to that second Test the match was won by England by eight wickets, and Evans did not concede a single bye in either Indian innings. It can’t have helped his cause that he was dismissed for a duck, but the real problem was as many as four stumping chances that were missed in that fifteen minute period. The unlucky bowler was the Lancashire leg spinner Tommy Greenhough. Two of the deliveries were googlies, which took off as they passed between bat and pad, and the other two kept low on the leg side. None were easy opportunities but for a man who had kept so well to Wright for so many years it was compelling evidence of a decline.

After the second Test Evans spoke to Peter May and was always adamant that May had told him to stay fit, a clear hint, so believed Evans, that he was to be taken to the Caribbean that winter. When the party was announced in July however the two ‘keepers were Swetman and Evans’ long time England deputy Keith Andrew. Always the bridesmaid Andrew won just two Test caps, almost a decade apart. He was an outstanding ‘keeper, but had few pretensions as a batsman.

The omission from the West Indies party greatly upset Evans, who then came under pressure at Kent. It may well have been a case of jumping before he was pushed, but he announced his retirement after the last match of the summer. He had passed a significant milestone, 1,000 dismissals (he was the eleventh man to achieve that record) and his deputy at Kent, Tony Catt, had been waiting in the wings for five years and the county were keen to keep him.

Retirement from Kent did not however take Evans away from the game and indeed it was to be another ten years before he played his final First Class match. He had a long association with the International Cavaliers, a wandering side not unlike Lashings of the present day, who attracted many big names from the ranks of the recently retired and overseas Test squads and played matches, generally but not always one day fixtures, up and down the country.

Evans’ final First Class fixture was for a Cavaliers side against Barbados and was played at Scarborough in 1969. Two years before that, a matter of days before his 47th birthday, he had answered an SOS from Les Ames to turn out for Kent. Alan Knott was making his Test debut and with no regular understudy Evans got the call. The opponents were the toughest there were, reigning champions Yorkshire. The champions triumphed by 7 wickets but Evans did very well. He scored 10 and 6, conceded just eight byes and held two catches. The consensus seemed to be he had lost little over the years.

Journalism called Evans after he left the game, as did broadcasting. In 1961 he published one of the more interesting cricketing autobiographies of the period. He was critical of May; He seemed to have no humour in him, not entirely convinced by Len Hutton; He didn’t handle people very well, and not entirely complimentary about Colin Cowdrey; sometimes he didn’t look like a very good batsman at all.

Best known of Evans’ post cricket occupations was a consultant to Ladbrokes to assist them in fixing odds for cricket, and he became a familiar sight in the company’s tents, sporting a hugely impressive set of mutton chop sideburns. He wasn’t necessarily the best at what he did though, he being responsible for setting odds of 500-1 at the famous Headingley Test in 1981. Whilst his employers most certainly caught a cold with that one and lost a good deal of money, the publicity generated by Dennis Lillee’s admission that he had trousered a goodly part of the loss turned out to be the best value advertising the company had ever had and Evans’ job was safe.

A born gambler like Evans tried his hand at a few business ventures, none of which made his fortune. The most enduring was an interest in a jewellery business established with an old college friend in 1949. The relationship lasted for a number of years before it ended acrimoniously, Evans somewhat cryptically accusing his former partner of being almost as big a scoundrel as myself. One definite benefit from the business was that the knowledge he gained enabled Evans to win £1,000 on a game show, Double Your Money, answering questions about jewellery. The equivalent amount today would be more than £20,000. Evans gave half the money to a charity of which his old England teammate David Sheppard was patron.

An investment in a chicken farm failed when many of the chickens managed to regain their freedom. A pitch drier Evans backed was not a success, managing to scorch the practice wickets at Canterbury, and a dice game in which he sank some money did not attract enough other interest to get off the ground. The most spectacular failure of all was his contribution to the purchase of some land at Walton on the Naze on the Essex coast. The project was an ambitious one, to construct a 500 chalet holiday site. The problem was the land was bought without the benefit of planning consent, which was refused, rendering the land all but worthless.

In the 1960s Evans also spent time as mein host at a pub in New Milton in Hampshire before moving on to the Drovers Arms in Petersfield. In this endeavour Evans was moderately successful although sadly his tenure saw the demise of his first marriage. He married again in 1973 and had a daughter, to add to his son from his first marriage. A 1990 biography reports that that marriage also ended in separation, although it would seem there must have been a reconciliation at some point. Evans died in 1999 at the age of 78, and his obituarists spoke of his second wife as being his widow.

Leave a comment