And Now the Greatest Writer of them all (IMO) Writes aBout Sir Garry Sobers :-

The greatest ever? Certainly the greatest allrounder today, 1967

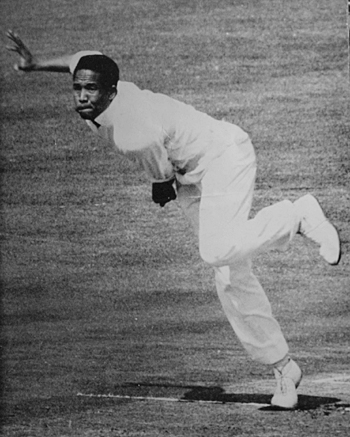

Sobers -- The Lion of Cricket

Sir Neville Cardus

Almanack home -1967 home

Garfield St Aubrun Sobers, 30 years old in July 1966 -- the most renowned name of any cricketer since Bradman's high noon. He is, in fact, even more famous than Bradman ever was; for he is accomplished in every department of the game, and has exhibited his genius in all climes and conditions. Test matches everywhere, West Indies, India, Pakistan, Australia, New Zealand, England; in Lancashire League and Sheffield Shield cricket. We can safely agree that no player has proven versatility of skill as convincingly as Sobers has done, effortlessly, and after the manner born.

He is a stylish, prolific batsman; two bowlers in one, fastish left-arm, seaming the new ball, and slow to medium back-of-the-hand spinner with the old ball; a swift, accurate, slip fieldsman in the class of Hammond and Simpson, and generally an astute captain. Statistics concerning him speak volumes.

Sobers holds a unique Test double, over 5,500 runs, and close on 150 wickets. Four years ago he set up an Australian record when playing for South Australia by scoring 1,000 runs and taking 50 wickets in the same season. To emphasise this remarkable feat he repeated it the following summer out there.

Only last January he established in India a record for consecutive Test appearances, surpassing J.R. Reid's 58 for New Zealand. He is also amongst the select nine who have hit a century and taken five or more wickets in one Test, joining J.H. Sinclair, G.A. Faulkner, C.E. Kelleway, J.M. Gregory, V. Mankad, K.R. Miller, P.R. Umrigar and B.R. Taylor.

Is Sobers the greatest allround cricketer in history? Once upon a time there was W.G. Grace, who in his career scored 54,896 runs and took 2,876 wickets, many of which must really have been out; also W.G. was a household name, an eminent Victorian, permanent in the national gallery of representative Englishmen.

Aubrey Faulkner, South African, a googly bowler too, scored 1,754 runs in Test matches, average 40.79, and took 82 wickets, average 26.58.

In 1906, George Hirst achieved the marvellous double performance of 2,385 runs and 208 wickets. When asked if he thought anybody would ever equal this feat he replied, "Well, whoever does it will be tired." But Hirst's record in Test matches was insignificant compared with Sobers', over a period. (All the same, shouldn't we estimate a man by his finest hour?)

There was Wilfred Rhodes, let us not forget. In his career he amassed no fewer than 39,802 runs, average 30.83, and his wickets amounted to 4,187, average 16.71. In first for England with Jack Hobbs at Melbourne in 1912, and colleague in the record first-wicket stand against Australia of 323; and in last for England in 1903, partner of R.E. Foster in a last-wicket stand of 130. Again, what of Frank Woolley, 39,802 runs in Tests, 83 wickets?

It is, of course, vain to measure ability in one age with ability in another. Material circumstances, the environment which moulds technique, are different. Only providence, timeless and all-seeing, is qualified to weigh in the balance the arts and personality of a Hammond and a Sobers.

It is enough that the deeds of Sobers are appreciated in our own time, as we have witnessed them. He has, as I have pointed out, boxed the compass of the world of present-day cricket, revealing his gifts easefully, abundantly. And here we touch on his secret: power of relaxation and the gift of holding himself in reserve. Nobody has seen Sobers obviously in labour.

He makes a stroke with moments to spare. His fastest ball -- and it can be very fast -- is bowled as though he could, with physical pressure, have bowled it a shade faster. He can, in the slips catch the lightning snick with the grace and nonchalance of Hammond himself. The sure sign of mastery, of genius of any order, is absence of strain, natural freedom of rhythm.

In the Test matches in England last summer, 1966, his prowess exceeded all precedents; 722 runs, average 103.14, 20 wickets, average 27.25, and ten catches.

In the first game, at Manchester, 161 and three wickets for 103; in the second, at Lord's, 46 and 163 not out and one wicket for 97; in the third, at Nottingham, 3 and 94, five wickets for 161; in the fourth, at Leeds, 174 and eight wickets for 80; in the fifth, at The Oval, 81 and 0, with three wickets for 104.

A writer of highly-coloured boys' school stories wouldn't dare to presume that the hero could go on like this, staggering credulity match after match. I am not sure that his most impressive assertion of his quality was not seen in the Lord's Test. Assertion is too strenuous a word to apply to the 163 not out scored then; for it was done entirely free of apparent exertion, even though at one stage of the proceedings the West Indies seemed beaten beyond salvage.

When the fifth second-innings wicket fell, the West Indies were leading by nine runs only. Nothing reliable to come in the way of batsmanship, nobody likely to stay with Sobers, excepting Holford. As everybody concerned with cricket knows Sobers and his cousin added, undefeated, 274.

It is easy to argue that Cowdrey, England's captain, did not surround Sobers with a close field. Sobers hinted of no technical flaw, no mental or temperamental anxiety. If he slashed a ball when 93, to Cowdrey's hands, Cowdrey merely let us know that he was mortal when he missed a blistering chance.

Bradman has expressed his opinion that few batsmen of his acquaintance hits with the velocity and strength of Sobers. And a sliced shot can travel at murderous pace.

At his best, Sobers scores as easily as any left-handed batsman I have seen since Frank Woolley. He is not classical in his grammar of batsmanship as, say, Martin Donnelly was. To describe Sobers's method I would use the term lyrical. His immense power is concealed, or lightened, to the spectator's eye, by a rhythm which has in it as little obvious propulsion as a movement of music by Mozart (who could be as dramatically strong as Wagner!). A drive through the covers by Sobers sometimes appears to be quite lazy, until we see an offside fieldsman nursing bruised palms, or hear the impact of ball striking the fence.

His hook is almost as majestic as MacLaren's, though he hasn't MacLaren's serenity of poise as he makes it. I have actually seen Sobers carried round, off foot balance, while making a hook; it is his only visibly violent stroke -- an assault. MacLaren, as I have written many times before, dismissed the ball from his presence.

The only flaw in Sobers's technique of batsmanship, as far as I and better judges have been able so far to discern, is a tendency to play at a dangerously swinging away off-side ball with his arms -- that is to say, with his bat a shade (and more) too far from his body. I fancy Sydney F. Barnes would have concentrated on this chink in the generally shining armour.

He is a natural product of the West Indies' physical and climatic environment, and of the condition of the game in the West Indies, historical and material, in which he was nurtured.

He grew up at a time when the first impulses of West Indies' cricket were becoming rationalised; experience was being added to the original instinctive creative urge, which established the general style and pattern -- a creative urge inspired largely by Constantine, after George Challenor had laid a second organised basis of batting technique. Sobers, indeed, flowered as West Indies' cricket was coming of age. As a youth he could look at Worrell, at Weekes, at Walcott, at Ramadhin, at Valentine.

The amazing thing is that he learned from all these superb and definitely formative, constructive West Indies cricketers; for each of them made vintage of the sowings of Challenor, George Headley, Constantine, Austin, Nunes, Roach, and Browne -- to name but a few pioneers.

Sobers began at the age of ten to bowl orthodox slow left-arm; he had no systematic coaching. (Much the same could safely be said of most truly gifted and individual cricketers.) Practising in the spare time given to him from his first job as a clerk in a shipping house, he developed his spin far enough to win a place, 16 years old now, in a Barbados team against an Indian touring side; moreover, he contrived to get seven wickets in the match for 142.

In the West Indies season of 1953-54, Sobers, now 17, received his Test match baptism at Sabina Park, Kingston. Valentine dropped out of the West Indies XI because of physical disability and Sobers was given his chance -- as a bowler, in the Fifth game of the rubber.

His order in the batting was ninth but he bowled 28 overs, 5 balls for 75 runs, 4 wickets, when England piled-up 414, Hutton 215. In two innings he made 14 not out, and 26.

Henceforward he advanced as a predestined master, opening up fresh aspects of his rich endowment of gifts. He began to concentrate on batsmanship, so much so that in 1955, against Australia in the West Indies, he actually shared the opening of an innings, with J.K. Holt, in the fourth Test. Facing Lindwall and Miller, after Australia had scored 668, he assaulted the greatest fast bowlers of the period to the tune of 43 in a quarter of an hour.

Then he suffered the temporary set-back which the fates, in their wisdom, inflict on every budding talent, to prove strength of character. On a tour to New Zealand, the young man, now rising twenty, was one of a West Indies contingent. His Test match record there was modest enough -- 81 runs in five innings and two wickets for 49.

He first played for the West Indies in England in 1957, and his form could scarcely have given compensation to his disappointed compatriots when the rubber was lost by three victories to none. His all-round record then was 10 innings, 320 runs, with five wickets costing 70.10 each.

Next he became a professional for Radcliffe in the Central Lancashire League, where, as a bowler, he relied on speed and swing. In 1958-59 he was one of the West Indies team in India and Pakistan; and now talent burgeoned prodigiously.

On the hard wickets he cultivated his left-arm googlies, and this new study did not in the least hinder the maturing of his batsmanship. Against India he scored 557, average 92.83 and took ten for 292. Against Pakistan he scored 160, average 32.0 and failed to get anybody out for 78.

The course of his primrose procession since then has been constantly spectacular, rising to a climax of personal glory in Australia in 1960-61. He had staggered cricketers everywhere by his 365 not out against Pakistan in 1958; as a batsman he has gone on and on, threatening to debase the Bradman currency, all the time swinging round a crucial match the West Indies' way by removing an important opposing batsman, or by taking a catch of wondrous rapidity.

He has betrodden hemispheres of cricket, become a national symbol of his own islands, the representative image on a postage stamp. Best of all, he has generally maintained the art of cricket at a time which day by day -- especially in England -- threatens to change the game into (a) real industry or (b) a sort of out-of-door Bingo cup jousting.

He has demonstrated, probably unaware of what he has been doing, the worth of trust in natural-born ability, a lesson wasted on most players here. If he has once or twice lost concentration at the pinch -- as he did at Kennington Oval in the Fifth Test last year -- well, it is human to err, occasionally, even if the gods have lavished on you a share of grace and skill not given to ordinary mortals.

The greatest ever? -- certainly the greatest allrounder today, and for decades. And all the more precious is he now, considering the general nakedness of the land.