Days Of The Demon

Martin Chandler |

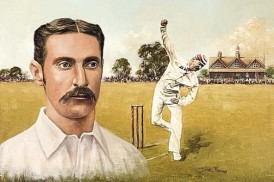

The place of Frederick Spofforth is an enduring one in Ashes folklore. The way the name trips from the tongue is a help, as is the fact that Spofforth played the leading role in the defeat of England at the Oval in 1882, the match that began the whole story. And then there is that splendid soubriquet, ‘The Demon’, and the Mephistophelian appearance of a man who tormented England batsmen through the first ten years in which Test matches were played.

His name apart however there is a general lack of familiarity with Spofforth. His time was before the days of moving pictures and indeed only after his best days were long behind him did the first action photographers start to focus their cameras on the men in the middle. The result of this is that there are many questions that it is now difficult to answer. Uppermost amongst them is the vexed question of just how fast Spofforth was, as well as the side issues that flow from that, as to what his action looked like and what, if anything, he did with the ball.

The man himself was, one suspects, responsible for at least part of the confusion as a story involving Sir Home Gordon illustrates. Gordon eventually inherited a peerage and died as the 12th Baronet Gordon of Elmo, Sutherland. For present purposes however the old Etonian, well known on cricket grounds for the large carnation he always wore, was a cricket journalist, author and publisher. He was not one of the best writers of his generation, nor always the most accurate, but he was an indefatigable enthusiast and great friend of the game. When he died in September 1956, just shy of his 85th birthday, it was unlikely there was a man alive who had seen as much cricket.

Gordon knew Spofforth well, and had first seen him play on the Demon’s first visit to England, back in 1878. On that occasion Gordon’s uncle took him to see the Australians play the Gentlemen of England at Prince’s, a famous old ground in Chelsea that made way for developers in 1883. Gordon relates that his Uncle had sympathy for any batsman dismissed by a really fast bowler, detesting the tearaway deliveries of FR Spofforth. As an eye witness it seems that at best Gordon only partly agreed with his uncle. Whilst describing Spofforth’s appearance with the ball in his hand as alarming, and producing the interesting observation that all his body and his limbs seemed to be coming at the batsman like a human octopus, his conclusion was that Spofforth was a master of the ball and could modify pace without suggesting it in his crescentic delivery, only sending down a devastating express now and then. That the Spofforth action was not a thing of beauty was confirmed by Richard Daft in his famous book Kings of Cricket, when he somewhat quaintly observed; the most favourable admirers can hardly call Mr Spofforth’s style a model of grace. It has withal a something truculent and overbearing (sic)

Finally getting closer to the point of the story Gordon’s proudest achievement as a writer was his editorship of The Memorial Biography of WG Grace, published in 1919. Nominally Gordon was only a co-editor, together with two cricketing Grandees, Lords Harris and Hawke, but in truth it was he who did all the work, and indeed later wrote Hawke’s autobiography for him. In any event as he put together his work on Grace Gordon naturally approached Spofforth. On a total of 19 occasions Grace fell victim to Spofforth, and his average in matches in which he had to face The Demon was more than 11 points lower than his overall First Class average. On being contacted by Gordon Spofforth confirmed he would be happy to relate to him all he knew about Grace, but only on condition he would describe Spofforth in the book as the fastest bowler there had ever been!

Long time Somerset skipper Sammy Woods, who played Test cricket for Australia and England as well as Rugby Union for England, was not quite a contemporary of Spofforth, although they did play together once for the Gentlemen against the Players. Woods is a useful judge, having a foot in both camps, and his verdict on Spofforth was he was medium fast with a fast yorker, and had more guile than any bowler I ever saw. He had a perfect follow through, and he delivered every ball with the same action, and as he looked all legs, arms and nose, it was very hard to distinguish what ball was coming along next.

One of the classic cricketing textbooks of the Victorian era was the volume on cricket in the Badminton Library, a book that ran to several editions and even in the 21st century is not difficult to track down. One of the major contributors was England all-rounder Allan Steel, one of Spofforth’s victims at the Oval in 1882. He describes Spofforth’s bowling as being over medium pace, coming back many inches and often getting up to an uncomfortable height, but ultimately suggests a very substantial range of speeds by echoing Woods; in his bowling the same run, action and exertion were apparently used for delivering a slow or medium paced ball as for a fast one.

The Honourable Robert Lyttelton, a member of a famous aristocratic English cricketing family, confirmed the versatility of The Demon, describing him as having tried and succeeded in all paces, except, perhaps, the very slow. William Ford, one of a famous brotherhood who was an accomplished player and later writer on the game was the same age as Spofforth. They appear not to have played against each other at First Class level, but Ford saw enough of Spofforth to feel able to write that he could, when required, bowl at great pace. As to what took the wickets Ford added that he could put on a big screw or a little screw without altering his pace.

Are we able to deduce anything now as to the circumstances in which Spofforth varied his pace? It seems clear that he did so almost at will, and the fact that 19 of his victims were stumped confirms that wicketkeepers would stand up to him, not of course an indication of express pace. It must be likely he slowed down with age, and we know he began his cricket as a fast underhand bowler, but reading his contemporaries comments it may be that he bowled with more pace on good wickets. His Australian teammate George Giffen makes the point that only on good batting pitches was Spofforth not the best bowler in Australia, judging Harry Boyle and George Palmer to be his superior on true surfaces.

The Demon was born on 9 September 1853 at Balmain, to an English father and a New Zealand mother. The first ‘big’ match he saw was at age eight when HH Stephenson’s English tourists played a XXII of New South Wales. Spofforth immediately decided to switch to overarm bowling and, impressed by the pace and extraordinarily long run up of George ‘Tear ‘em’ Tarrant, he tried to bowl as fast as he could.

It was another English side that made Spofforth stop and think next. He played for XVIII of New South Wales against WG Grace’s tourists in January 1874. Perhaps surprisingly the New South Welshmen won by eight wickets, dismissing the Englishmen for 92 and 90. Spofforth didn’t even get to turn his arm over in the first innings, and in the second returned figures of 13-7-16-2. What impressed Spofforth was the bowling of James Southerton, a slow bowler with immense control.

Three years later another private English tour, captained by James Lillywhite, visited Australia. Spofforth was injured for the first half of the season, but turned out against the tourists for New South Wales in mid January. He took just a single wicket as the tourists scored 270. New South Wales had to follow on, but in the end held on for a draw. Another English bowler of great control, the slow medium Alfred Shaw made an impression on Spofforth. The home side scored their runs at barely a run per four ball over.

Two months on, for the first time, all Australia locked horns with Lillywhite’s men. The match is now recognised as the first ever Test and was dominated by Charles Bannerman’s famous 165, 67.3% of Australia’s total, still a record more than 140 years later. Spofforth was invited to play but would only do so if Billy Murdoch was selected as wicketkeeper. Unsurprisingly the press, particularly in Victoria, accused Spofforth of arrogance – he was after all only 23, and had a career haul of just 20 wickets.

In the second Test, hastily arranged after Australia’s unexpected victory, both Murdoch and Spofforth played, although there was at least something of a climb down by Spofforth because Murdoch did not keep wicket. Lillywhite’s men recovered some pride by beating this apparently stronger Australian side by four wickets. Spofforth took four wickets in the match, and was not particularly effective.

It was in 1878 that, on his first tour of England, The Demon acquired his nickname and his reputation. On the tour as a whole, including matches against odds, Spofforth took 281 wickets at an average of 4.10. In the First Class games, of which there were 15, he took 97 at 11.01. In terms of averages he was bettered by another pace bowler, Tom Garrett whose figures were 103 at 3.28 in all matches and 32 at 9.93 in the First Class arena.

There were no Tests played on the 1878 tour, but strong opposition was played. Early on an MCC side led by WG Grace was beaten by nine wickets at Lord’s, and in the first innings were dismissed for 33, Spofforth producing the remarkable figures of 5.3-3-4-6 including a hat trick. In the second innings the hosts fared even worse after keeping their deficit to a mere eight, dismissed for only 19. Of those runs 16 came from the bowling of Spofforth, who took four wickets. This time the remarkable analysis came from Harry Boyle, 8.1-6-3-6. Even though the game started late at 12.03 it was completed in a day, on a pitch described as a quagmire. Elsewhere there were ten wicket hauls against Lancashire, Surrey, Gloucestershire and the Players, including in that match at Kennington Oval another hat trick.

The following winter Lord Harris took a side to Australia and one Test was played. Again it was not recognised as such at the time, indeed the expression only started to acquire the meaning it has today in 1894 when a South Australian journalist drew up what he considered to be a list of Test matches, an approach that has been adopted ever since. The match was clearly important however, the only one on the tour played against a side styled as Australia. Spofforth cemented his reputation as he helped his side to victory by ten wickets with 6-48 and 7-62 including the first Test hat trick. Harris’ men were some way short of the full strength of England, in particular there being no WG.

Australia and Spofforth were back in England in 1880, although as on their previous visit no Tests were scheduled. In the end one was added and WG made his Test debut and with it an innings of 152 in a comfortable England win. For Spofforth it was a good tour as he built on his reputation by topping the national averages with 40 wickets at 8.40. The pity was that by the time the Test match came round he was unfit, having broken a finger in a match at Scarborough.

Whilst it may seem that tours between Australia and England have increased in frequency in recent years they are still not as regular as they were in the 1880s and England were back down under in 1881/82. There were four Tests scheduled, two were drawn and two won by Australia. What is surprising is that Spofforth missed the first three Tests. Injury may have been in part responsible, he suffered a nasty injury in a fall from a horse at the beginning of the season, but that did not explain all three absences. It has been suggested there was a dispute about money, that conscious of his reputation Spofforth didn’t fancy the third Test as it was due to be played on a plumb batting wicket or that he was simply being arrogant and toying with the authorities and public alike. In truth one suspects that Spofforth was simply out of form and that he knew it. He did play in the last Test and managed the disappointing return of 1-128 in the match.

The lack of success continued in 1882 after Spofforth arrived in England. After five matches he had taken only eight wickets at a cost of almost 40 runs each. He played himself into form however and by the end of the summer 30 First Class matches had brought him a haul of 157 wickets at 13.24. There were five match hauls of ten or more and 16 five-fers, but the highlight was Spofforth’s display in the solitary Test. Murdoch won the toss and batted, a decision which, as his side plunged to 63 all out seemed a poor one, albeit less so when, largely due to Spofforth’s 7-46, the deficit was restricted to 38. Australia did do better in their second innings, but ultimately managed only 122 and England’s target of 85 appeared straightforward, particularly when they got to 52-2 with just the loss to Spofforth of the two Lancastrians Albert ‘Monkey’ Hornby and Dick Barlow. Pace wise this must have been The Demon at full tilt, contemporary reports stating that wicketkeeper Jack Blackham had to stand well back.

The character of the match changed when Spofforth decided to change ends and drop his pace. Almost straight away he got George Ulyett and Boyle removed WG to reduce England to 53-4. Alfred Lyttelton and ‘Bunny’ Lucas then dug in, playing out a dozen consecutive maidens at one point and lifting the score to 66. With both batsmen seemingly comfortable a single was then gifted and, at last with Lyttelton facing him, Spofforth made the breakthrough. He proceeded to take four quick wickets and with Boyle nipping out the last two Australia got home by eight runs and, next day, the famous obituary of English cricket appeared and the Ashes legend was born. Spofforth’s match figures of 14-90 were not bettered by an Australian for 90 years and Bob Massie’s two eight wicket hauls in the Lords’ Test of 1972.

The Honourable Ivo Bligh followed the Australians back to the Southern Hemisphere for a series of four Tests in 1882/83. Spofforth contributed little to the first Test, won by Australia by nine wickets or the second, won by an innings by England, nor indeed to the fourth which was won by Australia by four wickets to tie up the series. Perversely The Demon’s major performance came in the third Test, won by England, in which he took 11-117.

Back in England in 1884 Spofforth played in every single match on the tour, so it was hardly surprising that he was no longer bowling flat out. He had a magnificent summer, taking 207 wickets at 12.82. He was seventh in the national averages, and no bowler got within 70 of his haul of wickets. The next best amongst his teammates was Palmer with 132 at 16.43. Outside the Tests the summer was a long story of success for Spofforth and he took the fourth and last hat trick of his career against the South of England. His performances in the three Tests were less impressive, his ten wickets costing him 30 runs apiece. England won the only decided Test, the second, and to assist them in defending their lead the Surrey club produced a fine batting wicket at the Oval which the Australians made good use of, but although they reduced England to 181-8 in response to their 551 they let the tail wag to the tune of 165 and despite enforcing the follow on never looked like bowling England out twice.

Once more an English side followed the 1884 Australians back with a five match series in the offing. All five Tests were played but it was not a satisfactory series. Spofforth was simply not around for the first Test, marking Adelaide’s first attempt at hosting Test cricket. England won comfortably and after a row about money the South Australian Cricket Association ended up making a loss after trying to appease the two teams. The row rumbled on and for the second Test there was a players’ strike by the Australians. Their team thus contained nine debutants, five of whom never played again. Spofforth was again not available but made it very clear he disapproved of the strike action.

The passage of six weeks between the second and third Tests allowed some reflection and the Australians, back to full strength and now with Spofforth, won an exciting third Test by six runs. They certainly would not have done so without The Demon, who took 10-144 in the match. He took seven more in the fourth Test as the hosts tied matters up, bowling unchanged with Palmer through the England second innings of 77 in which he took 5-30. In the deciding match the Australian batsmen let them down and they lost by an innings. They won the toss and batted before Spofforth found himself coming in at the fall of the ninth wicket with the total on just 99. He had started his cricket career in the lower middle order with some pretensions to batsmanship. By 1885 he had slipped to last on the order but he did take this opportunity to show his teammates up, adding 64 for the last wicket with John Trumble and making exactly 50, his highest Test score.

By the time of the next Australian season, that of 1885/86, Spofforth’s banking career had taken him to Melbourne so it was for Victoria that he turned out in the Sheffield Shield against New South Wales. On debut he took ten wickets, and Victoria won by an innings. He was only destined to play a further four matches for his new state.

As had become the norm before a tour of England there was much speculation as to whether Spofforth would make himself available in 1886. Much of it seems to have been fuelled by the man himself but, as previously, in the end he travelled. Spofforth was not as successful as in the past. The three Test series was won 1-0 by England. Spofforth was comfortably Australia’s most successful bowler with 14 wickets at 18.59 but there were no more than four in any one innings. Overall his haul was well down, taking 89 wickets at 17.15. A month of the tour was missed after Spofforth broke a finger whilst fielding a drive from his own bowling by Lord Harris. He had suffered a similar injury, Harris again being the batsman responsible, in 1884, but this time the effects were more serious, Spofforth himself saying he was never quite the same bowler again, unable in the future to ever work on the ball in the way he had before.

Despite his troubles on the field the tour was a happy one for Spofforth who, in September, married Phyllis Cadman, the daughter of a wealthy businessman with a large portfolio of interests in the retail sector. Returning to Australia with his new bride Spofforth played one more Test taking just a solitary wicket in a narrow England victory. An era was over as the responsibility for the opening overs passed to Charles “Terror” Turner and James Ferris. The day of The Demon had passed.

There was only one more Southern Hemisphere summer in which Spofforth played any part at all, that of 1887/88. He played twice, not with any conspicuous success, before making what must have been a difficult decision to leave his own family in Australia in order to return his homesick wife and children to England. The decision was doubtless made rather more straightforward by the senior position that his father in law offered him within the family company.

The demands of business did not prevent Spofforth playing a very high standard of club cricket with Hampstead for many years and he also turned out for Derbyshire (not at that time a First Class county). Festival matches also attracted him and he did not play his final First Class match until 1897. The previous year had seen The Demon roll back the years. He played three First Class matches, the first for Wembley Park against Harry Trott’s 1896 Australians. The visitors won, but it would have been much easier for them if their old teammate had not taken 11 wickets for exactly 100. Three months later, for the South of England against Yorkshire, Spofforth had match figures of 9-82 in a losing cause before playing for the MCC against the Yorkshiremen. The match was badly affected by the weather and drawn, but 8-74 against one of the leading counties in their only innings was impressive stuff for a man who turned 44 a week later.

The Demon attended the 1921 Test at Trent Bridge and presented a medal to each of the Australian players to mark the occasion of the 100th Test between the two countries. He visited Australia during the 1924/25 Ashes series where he saw Australia win 4-1. Sadly he did not live to see his adopted country regain the trophy he had unwittingly helped to create two years later. The 72 year old died on the eve of the 1926 series, never having fully recovered from a bout of food poisoning earlier in the year. The measure of his success as a cricketer is a career tally of 853 wickets at 14.95, and as a businessman the Estate he left, which was the equivalent, on current values, of about nine million pounds.

Leave a comment