CB Fry – The Writer

Martin Chandler |

Charle Burgess Fry was born in April of 1872. He was undoubtedly the finest all-round sportsman of his era and, perhaps, ever. As a cricketer he was one of the great batsman of the ‘Golden Age’ and our own Dave Wilson has written about his life and playing career here and here.

One of Fry’s many talents was as a writer. He was as gifted an academic as he was athlete and, despite seemingly spending his time at university doing everything but academic work, he might still have achieved a first in Classics had not some, on this occasion thankfully short lived, mental health problems not dogged his final year.

Unlike some amateurs Fry did not have a family who could support him into adult life and indeed his father was, essentially, a mere accounts clerk in the Civil Service. Thus whilst the family could stretch to a private school education (at Repton) and a degree after that Fry had to work. Like many others in a similar situation he chose to become a schoolmaster, in his case at Charterhouse.

Fry graduated from Oxford in 1895 and spent three years at Charterhouse. He had done some writing whilst at University but, by contributing articles for publication found I could earn by journalism three times the income for the expenditure of a tenth of the time. He left teaching in 1898.

The first notable effort Fry made were a series of pen portraits that appeared Windsor Magazine. Unusually for the times Fry wrote under his own name and doing so no doubt helped create the interest that brought him enough work to enable him to leave teaching. The risk of doing so was that by making it clear he was a paid journalist he risked compromising his amateur status, and indeed he did stop competing in athletics events where attitudes were rather more unforgiving in that respect than in the worlds of cricket and soccer.

In terms of what sort of writer he was Fry was certainly a good one. In the days before Neville Cardus there tended to be little flamboyance in any sports writing, but Fry certainly had a nice turn of phrase. In the Windsor Magazine article to which I have referred he described Surrey pace bowler Tom Richardson as appearing something between a Pyrenean brigand, and a smiling Neopolitan, brimful of fire.

As well as the Windsor Magazine the Athletic News, Daily Express, Daily Chronicle, Lloyd’s News and Strand Magazine commissioned work from Fry. He also had a hand in his first book in the late 1890s, although he was never formally credited with it. The publication in question is Ranji’s Jubilee Book of Cricket, a wide ranging book that was partly instructional and partly historical. Accounts vary as to just how much of a hand Fry had in the writing of his great friend’s book but a significant part of the narrative appears to be his. Wisden apart the Jubilee Book of Cricket is perhaps the best known example of a Victorian cricket book and it ran to several editions, providing a welcome boost to the fragile finances of Fry and Ranji.

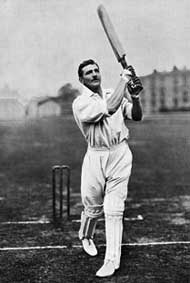

The first book published by Fry himself came in 1899; The Book of Cricket: A New Gallery of Famous Players. This is a large foolscap sized book which was originally issued in fourteen weekly parts and then returned to the publisher for binding. It is an imposing volume containing many full page portrait photographs of the players of the day and numerous other illustrations as well. As a luxury publication many copies of The Book of Cricket were well cared for and, 120 years after publication, a good copy can still be had for less than £50.

1899 was a significant year for Fry’s writing career as during it he became associated with The Captain, a magazine aimed at the schoolboy market. Fry wrote articles on cricket, and many other sports and outdoor pursuits and proved a substantial drawcard. Eventually the magazine were persuaded to put him on a contract of £800 a year in order to ensure he could not write for any other magazines. To put that in context it would be worth about £100,000 today.

The Captain continued until 1924 but never with any great financial success the problem, of course, being that as most of its readership were not in control of any significant sums of money there was little attraction for advertisers. The magazine was however popular and publisher George Newnes could see the potential for something similar that appealed to an adult audience and, in 1904, CB Fry’s Magazine was born. The sub-title, of action and outdoor life, confirm the broad base of Fry’s subject matter and Fry was very much a ‘hands on’ editor of the new title.

The most enduring of Fry’s contributions to cricket literature was published by Macmillan in 1905; Great Batsman: Their Methods at a Glance. It is a magnificent tome containing more than 600 photographs taken by George Beldam. The iconic image of Victor Trumper jumping out to drive is the best known, but the reality is that almost all of the instantly recognisable images of the stars of the ‘Golden Age’ originate from Beldam’s lens.

In his introduction Fry sets out his mission statement; The aim of this book is to answer the question ‘How do the leading batsmen play?’ That he succeeds in that ambition is what makes the book such an important one given that, for almost all of the batsmen featured, the book is by far the best record we will ever have of them, both in pictures and in words. The first and greater part of the book (about two thirds of it) deals with the eighteen greatest batsmen of the era including Archie Maclaren, Ranji, WG Grace and Fry himself.

I make no apology for dwelling on the subject of Trumper. In his introduction to each batsman Fry summarises his subject in a the space of a page or so. Of Trumper he writes he has no style, and yet he is all style ….. he defies all the orthodox rules, yet every stroke he plays satisfies the ultimate criterion of style – minimum of effort, maximum of effect , before summarising his strengths as a wonderful eye, a wonderful pair of wrists, and supreme naturalness, consequent on a supreme confidence that his wrist will never betray his eye. There follow as many as thirty of Beldam’s photographs of Trumper playing a variety of strokes including, of course, that one of him jumping out to drive.

The first is the descriptive part of the book. Part two, which opens up Beldam’s collection of images of some lesser known batsmen, contains what amounts to a technical treatise on the art of batting, told with reference to the photographs. Two years later in 1907, for once not falling out with his publisher along the way, Beldam and Fry produced the companion volume on Great Bowlers and Fielders. Perhaps the fact that Fry was a batsman rather than bowler did not help, nor that it is more difficult to capture the beauty of a bowler than a batsman in a still image, but the second volume did not and does not have quiet the same impact as the first and did not sell as well. What this means, a little perversely, is that in the 21st century, when almost all potential purchaser want both books, the second volume is a little more expensive and rather less frequently seen.

In 1907 there was also a second book published that bore Fry’s name. A Mother’s Son was a novel, co-written by Fry and his wife, Beatie, who was some years his senior. That relationship was an odd one to say the least. The future Mrs Fry was, as a teenager, involved in a major scandal with a wealthy banker (Charles Hoare) and that relationship, on some level at least, endured. Hoare set up the autocratic Beatie with a training ship for naval cadets which she ruled with a rod of iron. Fry, it would seem, played the role of amiable figurehead, but had little involvement with day to day life on the Mercury.

A Mother’s Son was quite well received, although modern critics wonder why. The storyline would have dated badly anyway in the intervening years, but even for Edwardian times the plot lacks credibility. There were probably some autobiographical elements. The central character of the story, Mark Lovell, was an all-round sportsman who on Ashes debut scored a century and took three wickets in an over, and all this before he had played any county cricket. The theory is, inevitably, that Lovell was based on Fry, and there are other characters who are adjudged by some to have shades of Beatie and Hoare.

It was in 1908 that Fry moved to the Mercury and the demands on his time then were such that eventually he was given an ultimatum and required to choose between his role there and the editorship of CB Fry’s Magazine. He chose the former and whilst he was to remain associated with the magazine he took very much a back seat. Eventually the Great War closed the magazine down and it did not appear again when peace returned.

There was one more book from Fry before the Great War, his detailed instructional book, Batsmanship. The book received some criticism at the time of publication as it advocated changes to long established practices, particularly in encouraging batsmen to use their feet. The book has worn well however, and to give just one example in 1998 acclaimed coach Bob Woolmer acknowledged Fry’s influence on his own methods and commented on how far ahead of its time the book was.

After the War Fry became involved with the League of Nations when Ranji was invited to become one of India’s representatives there, and in 1923 he published a book, Key Book of the League of Nations. There were also three attempts, in 1922, 1923 and 1924 to become a Liberal MP all of which failed, albeit in the general election of 1923 by only 219 votes. It was whilst in Geneva with the League that Fry was famously offered the throne of Albania, although the extent to which that was a genuine proposal rather than an elaborate joke by Ranji has never been made entirely clear.

In the 1920s Fry’s mental health deteriorated markedly and in 1929 he had a severe nervous breakdown the effects of which he struggled to get over. Once his health improved he began writing again and eventually made a recovery. After he had done so in 1934 he famously met and was received by Adolf Hitler and, in 1939, he finally published an autobiography, Life Worth Living: Some Phases of an Englishman.

As sporting autobiographies go, particularly from that era, Life Worth Living is a decent read, although it rarely refers to Beatie, and makes no mention at all of his failed attempts to get into the House of Commons nor, perhaps less surprisingly, his breakdown. Something that is mentioned, or at least was until it was removed as late as on its third reprint in 1947, was an account of Fry’s meeting with Hitler in Berlin. Like so many others Fry was captivated by Hitler’s charm

After the second world war Fry continued to do some commentary work, as he had done for the BBC since 1936 and would regularly contribute to periodicals and books by others. As late as 1955, a year before his death at the age of 84, he contributed a prologue and an epilogue to EW ‘Jim’ Swanton’s account of England’s Ashes success of 1954/55. Despite his advanced years and his not having been in Australia for the series it is clear from his writing that the advancing years had done nothing to diminish either Fry’s cricketing intelligence or his writing ability.

Fry’s status brought him into the orbit of people whose fame was already spreading far beyond Oxford, such as Max Beerbohm, the writer and caricaturist.

Comment by cryptoratedump.com | 11:06pm BST 4 September 2019