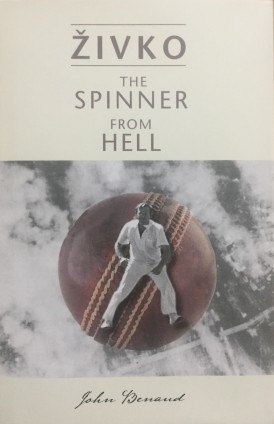

Zivko – The Spinner From Hell

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 120

Author: Benaud, John

Publisher: The Cricket Press Pty Ltd

Rating: 4 stars

Partial as I am to cricketing biographies I wouldn’t normally read one about an Australian whose closest brush with the First Class game was to play for New South Wales Colts against Queensland Colts in November 1968. That I was persuaded to do so is in part because publisher Ronald Cardwell told me Zivko was one of the best books to have borne his imprint. Now of course there is an element of ‘well he would say that anyway’ about such a comment, but when that view was endorsed by book dealer Roger Page I felt I had no choice but to invest.

Zivko is not a long read, just over an hour, but I can confirm that it does tell a fascinating story, and that the plaudits of Messrs Cardwell and Page are fully justified. The book’s author is the (very much – 14 years) younger brother of Richie Benaud, John. Benaud Junior also played Test cricket, three times, with a degree of success that shows that had he continued his playing career beyond the season in which all three of his Test appearances came he might have added substantially to that haul of baggy greens.

As it was Benaud pursued his primary career in journalism and also served as a Test selector for four years, a stint that prompted him to write Matters of Choice: A Test Selector’s Story, in 1997. As far as I am aware it remains his only previous book, although hopefully the praise that Zivko is going to receive will persuade him to pen an autobiography.

The subject of Zivko is Tony Radanovic, who was christened Zivko, a name that became, for the ease of English speakers, Tivko before finally becoming Tony. His father (Rajko to Ray) and brothers (Marian to Max and Thomislav to Tom) took similar nomenclative journeys. Mother Ana was more fortunate in that respect.

Ray and Ana Radanovic’s roots were in Yugoslavia and, during the Second World War, they found themselves, their country having surrendered to Hitler’s forces, transported to forced labour camps in Germany. These camps were not the same as the killing factories of the final solution, but the use of the words ‘forced labour’ make it clear what their lives involved.

When the German war machine was in its death throes the Radanovics, who before too long had Tony and then Max with them, became four of the many millions of refugees in Europe. At about the same time the then Australian government decided it needed an influx of labour, and what amounted to initial two year contracts were offered, one of which Ray accepted. He left for this new world first, Ana and the boys joining him several months later.

The conditions that the family encountered in Australia were not, in some ways, all that different from those they had left behind. But they had freedom and opportunity in Australia and, not without some twists and turns along the way, all of them made successes of their lives, and Benaud’s narrative includes all their stories.

As a cricketer Tony was an orthodox slow left armer, so had to contend with the hard wired Australian instinct for their leggies to be right arm wrist spinners. Without that it certainly sounds like Tony would have been good enough to have at least enjoyed a First Class career. As it was he had to be content with Sydney First Grade cricket, initially with the Benauds’ Cumberland, and then Bankstown. It says much of the man that he left the former because he was uncomfortable with a ‘mankading’ dismissal that one of his teammates performed.

At Bankstown Tony’s contemporaries included a pair of opening bowlers who both went on to bigger and better things, Len Pascoe and Jeff Thomson. There are some fascinating insights into both, particularly in respect of Thommo’s underwhelming Test debut against Pakistan which lulled Mike Denness’ England into that false sense of security that was so swiftly shattered in 1974.

The style of Benaud’s writing is certainly unusual. He could not be accused of being verbose, and indeed it is not uncommon for his sentences to consist of only a single word, usually ‘But’. So striking is the style that the experience had me hunting around for my copy of Matters of Choice: A Test Selector’s Story, and I can only conclude that either the passing of a quarter of a century has changed Benaud’s style, or he has deliberately chosen a different way of approaching the Radanovics’ stories. Either way it works very well, and this unorthodox book certainly gets my seal of approval.

Leave a comment