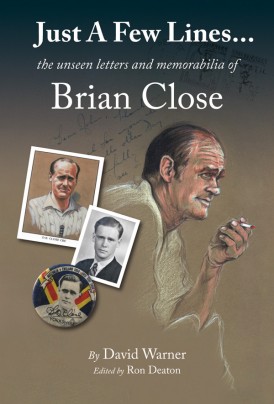

Just A Few Lines ……

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 256

Author: Warner, David

Publisher: Great Northern Books

Rating: 4.5 stars

In recent months the current pandemic has given us all a few glimpses of our own mortality, and I have had another one very recently from Just A Few Lines. Is it really all but five years since the Old Bald Blighter slipped off this mortal coil? This splendid new book and every other source confirms that, sadly, it is.

It was difficult not to be fond of Close, a man with just about every positive attribute there is, save perhaps the ability to fully do justice to his own talent. He did well enough though, captaining Yorkshire, England and Somerset, and if he didn’t score quite as many runs or take quite as many wickets as we would have liked he was always worth watching.

During his life there were a couple of Close autobiographies, although the first, Close to Cricket, published in 1968, is primarily concerned with the circumstances in which Close had lost the England captaincy the previous year, and barely mentions his younger self. A decade later and, just after his retirement, I Don’t Bruise Easily appeared. Ghosted by Don Mosey the book is a decent read, but with the story of a man who played Test cricket in four decades to tell in less than 250 pages once again Close’s early life is not dealt with in too much detail.

For obvious reasons it is counter-intuitive to describe a book published five years after its subject’s death as an autobiography, but that is essentially what Just A Few Lines is. In the days before home telephones became essential household items people who wanted to keep in touch with family and friends had to write letters, something even more important for the likes of Close who, by virtue of the nature of his calling, was seldom in the same place for too long.

In his early years Close corresponded on a regular basis with, it would seem, around twenty people. One of them was John Anderson, who Close met at primary school and was to remain a lifelong friend. Anderson himself died very soon after his old mate’s funeral. After his passing it turned out that he had kept around a hundred letters he had received from Close, the majority between 1948 and 1954, from which point on the telephone afforded an easier alternative for communication, and after that there are just a few letters that Close send to his friend from Pakistan during his tour there in 1955/56 when, presumably, telephones were either not readily available or, if they could be used, were prohibitively expensive.

Anderson’s sister gave the cache of letters, and other memorabilia her brother had assembled from and in respect of Close, to the latter’s widow. From there they found their way into the possession of the Yorkshire Cricket Foundation, where they will remain. David Warner has been a cricket writer for more than forty years and he has gone through the correspondence, interviewed Close’s widow, Vivien, and his few surviving childhood friends, and come up with this fascinating and detailed look at the early years of Close’s sporting career.

The first chapter of the book comprises the interviews with Vivien, Anderson’s older sister (sadly now also deceased), a former classmate, and a couple of elderly gentlemen who played cricket with Close more than seventy years ago, one of them former Yorkshire teammate Bryan Stott.

The letters begin in the second chapter, essentially transcribed as they were written and held together by an important but concise and unobtrusive commentary from Warner. There are a number of black and white photographs of the young Close, most of which I had not seen before, and some excellent full colour reproductions of some of the letters and other items of memorabilia associated with them.

The main result of putting these letters together is to demonstrate the sort of man that Close was. His sporting deeds do not often feature in the letters in any detail, Close often making the point that Anderson can read about those in the press. So the letters dwell at length on Close’s ‘extra-curricular’ activities and he certainly knew how to enjoy himself. Cinemas, theatres and parties feature extensively and Close is also keen to report back to his friend on the culinary luxuries he had enjoyed in what, for most, was still very much a time of austerity in Britain.

There is some cricket in the letters, but as much on the subject of Close’s football career, and his National Service. It is often forgotten that there was a time when Close played for the mighty Arsenal and, on either side of that, was at Leeds United and Bradford City before, surely sensibly, taking the view as a 21 year old that a serious knee injury should spell the end of his soccer career in 1952.

Bearing in mind that he was a teenager when the correspondence began, and of course was just 18 when he made his Test debut in 1949, it is perhaps not surprising that female company is important to Close, and he seems to have taken full advantage of the opportunities that his sporting prowess gave him to meet the fairer sex. There is nothing overtly salacious in the letters, although I was left wondering whether the ‘usual goodbye’ was some sort of coded comment.

The overriding impression created by Close’s letters is to underline just what a great time he was having and, surprisingly, that includes during the tour of Australia in 1950/51. Received wisdom, confirmed by I Don’t Bruise Easily, is that Close had a miserable time in Australia, lacked support and was treated less than kindly by some of the senior players on the tour. That in terms of runs and wickets he did not do particularly well on the trip is clear from the most cursory look at the tourists’ record, but nonetheless Close’s letters to Anderson demonstrate that the touring experience was something he thoroughly enjoyed.

Interesting too are Close’s letters home from that MCC ‘A’ Tour of Pakistan, albeit not for the reason that I had hoped. Although there are hints Close makes it clear to Anderson that the full story of the incident that threatened the future of the tour, the ‘water treatment’ practical joke that was played on umpire Idris Begh, will have to wait until he sees him following his return. But Close’s letters from Pakistan are never less than entertaining, particularly his comments on the general standard of the local umpiring.

And finally, there is one last touch worthy of mention, that being a nod back towards the era in which the letters were written. The first page of each chapter contains, after the title and before the narrative begins, a few short phrases that sum up the content to follow something which, in years gone by, was commonplace in sporting biographies and autobiographies. It is a style that you virtually never see these days, and its presence in Just A Few Lines reinforces the message that the book is a period piece in twenty first century clothing. All in all it is an excellent read, and highly recommended.

Leave a comment