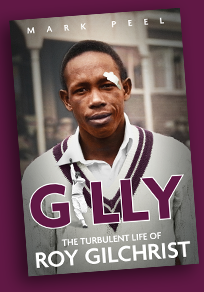

Gilly

Martin Chandler |Published: 2023

Pages: 224

Author: Peel, Mark

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 4.5 stars

The bare bones of Roy Gilchrist’s cricket career are that he played 13 times for West Indies in the late 1950s, and took 57 wickets at 26.68. Those stats show that Gilchrist was a decent player, but they are not so remarkable as to suggest that more than sixty years after his last Test, and more than twenty after his passing, a biography was likely to appear.

In truth however the real surprise is just how long it has taken for a writer to decide to commit the Gilchrist story to paper, as even a moderate author would surely have been able to write a decent book on him. The fact that the man who eventually took on the task, Mark Peel, has a track record as an accomplished biographer is, effectively, a copper bottomed guarantee that Gilly was going to be well worth reading.

The reason for Gilchrist’s Test career being cut short arose, as is widely known, as a result of his being sent home from West Indies’ tour of India and Pakistan in 1958/59. The cause of his disciplinary issues on that tour arose out of a mutual antipathy between Gilchrist and his captain, Gerry Alexander, and although he was never actually given any sort of official ban, and there were some who wanted to see him picked later, in the event he remained persona non grata and, one match in the Caribbean two years later and six in India the year after that apart, his First Class career was over at 25.

As well known as the ‘sending home’ incident is what Gilchrist did next, terrorising league cricketers in Northern England as he plied his trade there for the next two decades, and many are also aware of his most notorious appearance before the English courts, for wounding his wife by holding a hot iron to her face.

The 1958/59 tour has never been fully chronicled, and league cricket in England has rarely been widely reported. There has therefore never been an objective look at Gilchrist’s life to go alongside his inevitably self-serving and, to be frank, not very good autobiography, that appeared back in 1963, Hit Me For Six.

And objectivity is not always easy to find where Gilchrist is concerned. The incident with his wife is enough to turn anyone against him, and he remains the only cricketer I have come across who genuinely believed that the beamer was a legitimate delivery. In addition Gilchrist was quite happy to bounce tailenders, and to bowl as quickly and as menacingly as he could at batsmen who lacked the necessary technique and/or experience to be able to deal with him. He didn’t always bowl either. Fundamentally there was nothing wrong with the Gilchrist action, but as with the intentional beamer there were deliberate throws as well.

But whatever the reader may think of Gilchrist his story remains unique, and fascinating. It is brilliantly told by Peel as well. It would probably have been a good book if he had confined himself to researching Gilchrist through the books and newspapers listed as his sources, but he does a great deal better than that. No fewer than 59 individuals, including Jackie Hendriks who was in the 58/59 touring party, are thanked for their assistance and, in addition, the partner Gilchrist lived with after his return to Jamaica, their daughter and fellow West Indian fast bowler and long standing friend Chester Watson get a special mention for their help.

Peel begins by presenting his reader with a concise history of Jamaica, the purpose of which is to explain the grinding poverty into which Gilchrist, the youngest of at least 20 siblings, was born. The book then devotes three chapters to Gilchrist’s Test and First Class career before rather more space is taken up with his long career in the leagues and, finally, a rather sad decline after he returned to his homeland in 1986. The majority of ‘the 59’ were men who encountered Gilchrist in the leagues in England and there are many stories about his exploits here. Many of those tales fit in with the stereotype of Gilchrist that most readers will expect to meet, but there are others which show or hint at more positive aspects of his character.

So what did I make of Gilchrist by the time I finished reading Gilly? It’s a tricky question, and I can’t say I look on him with the fondness and affection that the likes of Wes Hall and Chester Watson do. But I was left with no doubt that there were occasions when Gilchrist was more sinned against than sinner, and that there were some positive character traits even if, overall, I found it impossible to avoid concluding what I already believed, that Roy Gilchrist was, essentially, what my late mother would have described as ‘a nasty piece of work’, albeit one who, like so many others who fit the description, clearly mellowed with age.

As far as the book itself is concerned it is one of those, relatively rare amongst cricketing biographies, that once picked up is difficult to put down. I suspect that come awards time Gilly will be on every long list, most short lists, and surely will come out on top somewhere. As cricket books go it is just about perfect, my one grumble being the lack of any sort of statistical appendix, something which would have been particularly useful with Gilchrist given that so much of his career was spent in leagues that are not well served by statisticians. But that is a very minor point – Gilly is a superb read, and highly recommended.

Leave a comment