The Rise and Fall of Les Smith

Martin Chandler |

Even at the end of his cricket career if asked to sign his name what was generally forthcoming was plain old “L.Smith”. Yet in the record books you will find his career details under the name Leslie O’Brien Fleetwood-Smith, a grand name for a man who remains to this day the greatest exponent of his art that the game of cricket has seen.

The affectation of the double-barrelled name, which simply added his father’s christian name to his surname, came about when Chuck, a nickname his father gave him as a child, first moved to Melbourne in order to try and ply his trade as a cricketer. His family, who to be fair to them had made a success of their lives, were very keen for their talented offspring to be seen as rather more than just an ordinary lad from up-country.

One of the game’s most engaging and eccentric of personalities Chuck was that rarest of cricketing creatures, the left arm wrist spin, or “chinaman” bowler. He turned a cricket ball prodigiously, and had a googly and top-spinner that were very difficult to pick. According to his contemporary and fellow wrist spinner, Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly, Chuck could spin the ball more than anyone else in the game, and was the best left arm spinner of his time. O’Reilly, himself without doubt an all-time great, always waxed lyrical about the Victorian, writing once that if he had just half of Chuck’s ability I never would have been worried about bowling against a team which had eleven Bradmans

There is a story that Chuck became what he was purely by accident, having bowled with his right arm until that was broken thereby forcing him to switch. It was a tale that the man himself did little to correct, but the truth was a little more mundane. Chuck was one of the fortunate few who is truly ambidextrous. His first instinct was indeed to bowl with his right arm, but the switch occurred when, as a result of the draining effects of a bout of influenza, he turned himself round one day when his right arm tired. Contrary to his instincts he found that he bowled better with his left arm than with his right, and the die was cast.

Chuck’s family came from Stawell, a gold rush town about 150 miles from Melbourne. Fleetwood-Smith senior was associated with the local newspaper and was able to send both his sons to Xavier College in Melborne, where Chuck, the younger son, and the ill-starred Karl Schneider dominated the cricket XI. Unfortunately for Chuck, although it is doubtful whether he himself was overly troubled by it, he was unable to complete his education. The reason for that cannot now be confirmed but it seems generally accepted that he was expelled, although the reason is not clear. What is known is that both his drinking and his interest in the fairer sex were already well-established, and it seems likely therefore that those were at the very least factors in the background of the expulsion.

Chuck returned to Melbourne for the 1930/31 cricket season in order to play for St Kilda, whose side contained Bill Ponsford as well as two Test match spinners, Don Blackie and Bert ‘Dainty’ Ironmonger. The bow-legged off spinner Blackie remains the third oldest debutant in Test cricket, and Ironmonger the fourth. Both were 46 when they first played for Australia, although at the relevant time Ironmonger claimed to be 41. Chuck also lied about his age when he joined St Kilda, and it was many years before the game’s statisticians became aware that he was born in 1908 and not 1910.

So impressed were St Kilda with the (in their eyes) 20 year old chinaman bowler that they played all three spinners, and Chuck had an excellent first season. He went from strength to strength the following year and had some remarkable early First Class games for Victoria. His debut was against Tasmania, and he began with a match haul of 10-145 in an innings victory. Six weeks later he was selected to play against the touring South Africans and, in the tourists’ only innings, he took 6-80. A month later and he made his bow in the Sheffield Shield against South Australia. Victoria won by an innings, and Chuck’s contribution was 11-120.

In the close season of 1932 Chuck was invited to join the side raised by Arthur Mailey that undertook an arduous 100 day tour of North America involving 51 games. Over the tour as a whole Chuck claimed 249 wickets at a cost of around 8 runs each. There was therefore real expectation that he would play against Jardine’s England the following season, and word of his exploits and abilities had also reached the ears of the England captain.

The Bodyline series remains a talking point amongst cricket fans throughout the world to this day, and Jardine’s plans to subjugate Bradman have been the subject of more than twenty books, one novel, a television series and at least one serious proposal for a feature film. Much less remembered, but just as meticulously prepared and ruthlessly executed, was the plan to keep Chuck out of the team altogether. He first encountered the tourists in the state game in the lead up to the first Test. The drama unfolded on the second morning of the game. Years later Walter Hammond wrote I was chosen as the ‘murderer’ and the victim was Fleetwood-Smith. England’s finest batsman scored a rapid 203, and made sure Chuck could never settle.

Despite the mauling from Hammond, and a couple more from Bradman in the Sheffield Shield, there were still 50 wickets for Fleetwood-Smith at 21.90 that season, so against anyone other than the very best he was lethal. It would have been interesting to see just what Jardine might have made of the eccentricities that Chuck would demonstrate whilst bowling. He had a low boredom threshold and Jardine, never at his happiest against spin, would doubtless have suffered from the full repertoire.

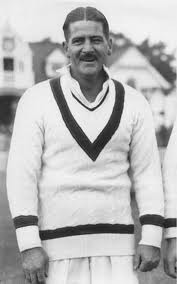

Between deliveries Chuck would mimic the call of a magpie, or a whipbird. He would chant the name of his favourite football team when he tired of wildlife impersonations, or burst into song, I’m in the mood for love being a particular favourite. In the outfield he would practice his golf swing, and on occasion enjoy a cigar, and there were many ad libs and many other impromptu means of entertaining the crowd were deployed by the tall handsome bowler with the matinee idol good looks, who was variously compared to Clark Gable and Erroll Flynn, two of the Hollywood hearthrobs of the day. The public loved the antics, but it is difficult to imagine a sense of humour failure from Jardine being anything other than virtually instantaneous.

Chuck came to England with Bill Woodfull’s side in 1934 and was therefore a member of the side that retook the Ashes after Bodyline. He didn’t play in any of the Tests, Clarrie Grimmett and O’Reilly being the two spinners amongst the three specialist bowlers Australia played in the big games, but on the tour as a whole he was the leading wicket taker, running through many county sides and, to his great satisfaction, getting the better of Hammond on the two occasions he bowled to him, once with a googly and once with a top spinner, neither of which the great man picked.

Bradman missed the 1934/35 season as a result of the after effects of an appendectomy he had undergone in England, so with no one to torment him Chuck took 63 wickets at a fraction over 20. By coincidence 63 was also the number of runs that he scored in the first innings against Queensland in December. Chuck wasn’t generally interested in batting, but on this occasion he took part in a harum scarum last wicket partnership with pace bowler Ernie McCormick who ended up with an unbeaten 77. Like Chuck McCormick never managed another half-century. They must have been two remarkable innings to watch. Difficult as I find it to believe in his splendid biography of Chuck, A Wayward Genius, Greg Growden states that between them the pair were dropped as many as 24 times during the partnership.

The early 30s brought good times for Chuck outside the game as well, and at the end of the season he married for the first time, to the daughter of a wealthy soft drinks magnate. There was a car from his father as a gift, and for the first time a “proper” job, not that Chuck did much. His father-in-law saw the benefits of having the gregarious and immensely popular sporting celebrity on the pay roll as a “sales representative”, which in reality meant Chuck could spend whatever hours he chose putting his face around bars and hotels socialising, and perhaps occasionally winning the odd new customer.

In the 1935/36 season Australia were due to visit South Africa. With the squad to consist of just fourteen it was not certain that Chuck would go, but without their run machine, Bradman choosing to stay in Australia on medical advice, the selectors decided to take their best bowling options and Chuck made the trip. With all three spinners being chosen for the game, he made his Test debut in the first match of the series. He took 4-64 in the first innings, but snared just five more victims after that before a finger injury sustained whilst fielding to his own bowling forced him to miss the latter part of the tour. Not that that seems to have upset Chuck greatly, his prodigious appetite for the ladies keeping him fully occupied, and his marriage vows very much to the back of his mind.

The injury turned out to be a persistent one, and with an Ashes contest in the offing for 1936/37 Chuck was sufficiently worried about his finger to book into a private hospital for treatment. He felt obliged to decline an invitation to play in the Test trial, although given that Bradman took a double century from the attack that went to South Africa that was perhaps no bad thing. Then England won the first two Tests, and once he did venture back into Shield cricket Chuck took 15-96 against Queensland. With another good performance against New South Wales to follow his recall was assured. He missed out on bowling on the sticky dog that England were caught on in their first innings but took his first Test five-for in the second innings as Australia wrapped up a huge victory in the third Test.

It was after this match that Chuck, O’Reilly, McCabe and Darling, Roman Catholics all, were summoned to a meeting with the Board. The enquiry broke down in a state of some disarray but was clearly called as a result of what was perceived as a lack of support for skipper Bradman during the first two Tests. Why the discussions should then involve Chuck is wholly unclear and Growden, writing in 1991, could only express the hope that one day when the Board’s records were opened up the reason for and background to the meeting might be revealed. In 2004 the Board allowed David Frith and Gideon Haigh full access to their records, but disappointingly that took us no nearer to knowing whether, as O’Reilly always believed, Bradman was the agent provacateur for the meeting.

Whatever ill-feeling the incident might have caused it still inspired Chuck to the defining moment of his Test career in the fourth match at Adelaide. England, still 2-1 up, took a first innings lead of 42. Chuck bowled more overs than any of his teammates, 41.4, and took 4-129. The final day dawned with England on 148-3 seeking 392 for victory. Hammond was the big hope, and he was unbeaten on 39. He got no further, Chuck producing a superb delivery that drifted away from the great man, pulling him forward, and then breaking sharply back in and bowling him. O’Reilly later wrote that he would unhesitatingly describe the delivery as the best he had ever seen in a Test match.

Hammond’s dismissal was the end for England and Chuck went on to his Test best 6-110 and his only ten wicket match haul. The great English scribe Neville Cardus wrote, Fleetwood-Smith won the match by wonderful spin. He quickly overwhelmed Hammond, Leyland, and Ames with balls deadly in their swift break, and beautiful in their seductive curve through the air. The wicket was his accomplice, though to most other bowlers it would have helped only now and again. I cannot imagine the batsman who could have avoided for long the snares of Fleetwood-Smith. It can hardly be said that England collapsed. They got out by the inexorable law of cause and effect.

On his home ground at the MCG Chuck chipped in with four more wickets in the last Test as Australia took the series 3-2 after being 2-0 down. It was the high point of Chuck’s career.

There was never any question but that Chuck would travel to England in 1938, but as he approached 30 he felt he may be getting just a little heavy, so he decided to take up wrestling, the theatrical sort. Growden’s description of his appearance on those occasions as Dressed in garish yellow tights, baby oil smeared all over his body, ridiculously flipping his immaculate hair into a fuzzy bundle on top, and uncharacteristically scowling. makes the absence of any photographic evidence of the episode most disappointing.

Perhaps all the choreographed grappling affected him. Most observers of his bowling in 1938 were agreed that Chuck’s bowling was not as good as it should have been, although his overall record of 88 wickets for the tour was impressive enough, and outside the Tests few batsman handled him with any degree of confidence. In the Ashes matches he started with 4-153 at Trent Bridge in England’s massive 658-8 and was Australia’s best bowler. There were just a couple of wickets in the drawn second Test and, due to the Manchester weather, the sides never took to the field in the third match of the series. Australia then went 1-0 up at Headingley. In a low scoring game O’Reilly was Australia’s most successful bowler, but without Chuck’s 3-73 and 4-34 it is unlikely that Australia would have got home. What really ruined Chuck’s figures was his return of 1-298 in England’s victory in the timeless Test at the Oval. He was however able to look back on the fact that his one victim was his old nemesis Hammond and that, had Len Hutton, on his way to his then record 364, been stumped when Ben Barnett spurned a very easy opportunity when he was on 40, England might well have got a great deal less than 903-7. Without the need for a desperate Bradman to then have a bowl himself, and damage his ankle and as a result be unable to bat, that defeat by an innings and 579 might well have been averted, so despite his dreadful figures Chuck was not to blame.

Off the field Chuck again enjoyed himself throughout the tour, and was not particularly discreet about it. Gossip abounded about his extra-marital activities, including one that involved a Duchess. These rumours found their way back to Melbourne, and were heard by both Mrs Fleetwood-Smith and her father. In the end the Board relented on their strict “no wives on tour” policy and permitted Jessie Bradman and Mollie Fleetwood-Smith to join their husbands after the final Test. Not surprisingly other members of the team described the relationship between the Fleetwood-Smiths as strained.

There were two more seasons of Shield cricket for Chuck before the domestic First Class game in Australia finished for the duration of the Second World War. Chuck was nothing like as prolific as previously. It cannot have been age, as he was not even 32 when his cricket career ended, but he was drinking more and more by this time and without the lure of the international game his interest was doubtless on the wane.

Chuck has become a man who is always looked upon as a cricketer who failed to live up to expectations, and indeed that was the general feeling amongst knowledgable onlookers during his playing days, but his overall record of 597 wickets at 22.94 is up there with the best, the more so when it is borne in mind that when he passed 500 wickets his average was the lowest of any man to reach that milestone. If a bowler is measured by his strike rate Chuck’s 44 looks impressive alongside those of his great contemporaries O’Reilly (48) and Grimmett (51).

The war years were not a particularly good time for Chuck. He joined up quickly, but his personality meant that he found it very difficult to either follow or give orders, something which was of course a fundamental impediment to a successful military career. Inevitably his marriage broke up, his father-in-law finally finding a cache of correspondence that evidenced Chuck’s serial adultery beyond doubt. Dismissed from his job and thrown out of his home as a result Chuck could not even turn to his own family for solace. Blood is thicker than water is an old truism that anyone involved in family law quickly learns. Chuck’s family however had grown close to their daughter-in-law, and his situation was a case of the exception that proved the rule. Chuck even managed, towards the end of the war, to have a very public falling out with Bradman in a restaurant. Growden could not find out why, although the explanation appears straightforward. The pair were chalk and cheese, but the perception was that whilst Bradman could help him Chuck was more than happy to ingratiate himself with his captain. In truth it is difficult to imagine that Chuck did actually like Bradman so, once his former skipper could be of no more assistance to him and an opportunity presented itself to Chuck to tell him exactly what he thought of him, it is not so surprising that he did, particularly as any possible inhibitions would doubtless have been lessened by a goodly intake of alcohol.

A man with as fitful a work ethic as Chuck was always going to suffer once he had to make his own way in life and as he became more dependent on the demon drink he became less and less able to carry out any work in order to pay for it. He did marry again, in 1948, in a far less ostentatious ceremony than his first marriage, but that marriage too was eventually to fail. As Chuck could not hold down a job for longer than it took to drink his way through whatever wages he could pick up his life went on a downhill spiral until he ended up sleeping rough, scavenging for food in rubbish bins, and devoting his life to finding his next drink.

The deterioration went on for years but Chuck, always honest despite whetever other problems he had, was left alone by the Melbourne police to get on with his sad existence, until eventually he was finally arrested on charges of larceny (theft) and vagrancy, when he was one of two men identified as being responsible for the theft of a woman’s handbag. He was found not guilty of the larceny, but guilty of vagrancy.

In English Law we have the Vagrancy Act 1824 which creates an offence of, effectively, being homeless and down on your luck. It is still on the statute book, repugnant as such a concept is in a civilised 21st century society, but is not much used, and on those rare occasions I have seen it deployed the purpose of so doing was less to demonise and more to try and secure assistance or sound a warning. Bindovers and discharges are the usual disposal, although in theory a short custodial sentence is available to an English court.

In Victoria however there was at the time the recently passed Vagrancy Act 1966, a piece of legislation that is far from simple and creates offences that can be committed in a variety of ways and which contain a number of different penalties. Unfortunately Growden did not write his biography with a readership of lawyers in mind, let alone ones who practice in a different jurisdiction, but I will assume for these purposes that Chuck’s offence was the least serious possible – it still carried with it the possibility of a twelve month custodial sentence.

After Chuck was remanded in custody following his conviction the world finally realised the extent of the fall from grace that had been suffered by a former international sportsman. Old teammates (especially Leo O’Brien) and friends rallied round, money was contributed to a fund to help Chuck and bail was arranged. Perhaps most surprisingly of all the second Mrs Fleetwood-Smith offered to take her estranged husband back, and to support him in an attempt to rebuild his life. This groundswell of support inevitably and quite properly led to Chuck avoiding a custodial sentence, and he returned home with his wife.

For many the story of Chuck Fleetwood-Smith ends with his descent into the chaos of life on the streets, but fairness demands that the rest of his story is told. Firstly and most importantly he was able to steer clear of alcohol and slowly regained his dignity. He even managed to obtain employment as a cleaner at one point, although his employer eventually had to let him go. The reason was not related to alcohol, absenteeism or incompetence but was due to Chuck being Chuck. He spent far too much of his time at work regaling a willing audience of his workmates with tales of past conquests, some on the cricket field and some at rather different venues. A natural raconteur Chuck thrived on the attention, but businesses cannot be run on goodwill and bonhomie alone, so he had to go.

Despite this setback Chuck was not lost to the world of work as he and his wife moved into a guest house that she ran. Chuck was handed the responsibility of looking after the gardens, a task to which he applied considerable care and not a little skill. It was undoubtedly the most congenial employment he had enjoyed since giving up the dark art of left arm wrist spin. He carried on like that until August 1970 when complications following a routine prostate operation led his doctors to give up on him. Chuck amazed them all by fighting that one off and returning home, but the years of neglect had taken their toll and next time he was hospitalised he did not survive. He died on 16th March 1971, a fortnight before what would have been his 63rd birthday.

News of Chuck’s death brought forth a fulsome stream of tributes and eulogies from a myriad of sources and, for the last time, he was box office again. Once his passing became old news he reverted to being the impressively named L. O’B. Fleetwood-Smith, a name enshrined in the annals of cricket as the most successful bowler of his type who had ever played the game. In the forty odd years that have passed since then South African Paul Adams, he of the bizarre ‘frog in a blender’ action, has taken more wickets, in many more Tests, but I do not believe anyone has ever seriously suggested that he can approach Chuck’s pre-eminence.

In casting around for a quote with which to finish this feature I have been faced with a bewildering choice, most of which were kindly provided by Greg Growden, but I am going to turn away from that particular source and go to a book called So This is Australia by the English journalist William Pollock, who wrote that interesting if rarely remembered book on the 1936/37 series. It did not follow the usual pattern of tour books of the time, being rather more discursive than the norm, but it has some interesting observation, none more so that Pollock’s summary of Chuck as The best worst bowler in international cricket. He puts up some of the most awful tripe ever seen and then, suddenly, he sends along something unplayable.

Martin, I agree the lack of photographic evidence of Chuck as a wrestler is a shame. Two references in my research to Chuck and wrestling – neither quite as exciting as Greg Growden describes. 1 Before 1937/38 season, Chuck was getting in shape, and worked with police wrestlers \”devising fresh

methods of developing peculiar muscles to swerve the ball into new tangles\” (Townsville Daily Bulletin Thu 26 Aug 1937). 2 While briefly serving at Army Phyd Ed School at Frankston in Oct 1940, he refereed a wrestling match between Bonnie Muir and Kiwi wrestler King Elliott, and in true WWE style had his shirt torn off before disqualifying Muir. njc

Comment by Nicholas Cowell | 12:00am GMT 23 March 2014